I decided to replace today’s Monday Musings with an awards announcement, because the NSW Premier’s Literary Awards were being announced tonight, and they comprise a swag of prizes, many being of particular interest to me. But, then I was shocked to hear that Australian poet Les Murray had died, and I couldn’t let that pass either, so you have a double-barrelled post tonight!

NSW Premier’s Literary Awards

I will only report on a selection of the winners, but here is a link to the full suite. And, if you are interested to know who the judges were, they are all listed on the award’s webpage.

Book of the Year: Billy Griffiths’ Deep time dreaming: Uncovering ancient Australia

Book of the Year: Billy Griffiths’ Deep time dreaming: Uncovering ancient Australia

The Christina Stead Prize for Fiction: Michelle de Kretser’s The life to come (my review).

People’s Choice Award for Fiction: Trent Dalton’s Boy swallows universe (my review)

The Douglas Stewart prize for Non-Fiction: shared between Billy Griffiths’ Deep time dreaming: Uncovering ancient Australia and Sarah Krasnostein’s The trauma cleaner (my review)

The UTS Glenda Adams Prize for New Writing Trent Dalton’s Boy swallows universe (my review). I love that in his thank you speech, he spoke about the time he spent with Les Murray in 2014. Murray, he said, shared his poem Home Suite, telling Dalton not to be afraid to go home. Going home, he said, is exactly which he did in his novel.

The UTS Glenda Adams Prize for New Writing Trent Dalton’s Boy swallows universe (my review). I love that in his thank you speech, he spoke about the time he spent with Les Murray in 2014. Murray, he said, shared his poem Home Suite, telling Dalton not to be afraid to go home. Going home, he said, is exactly which he did in his novel.

Multicultural NSW Award: Michael Mohammed Ahmad’s The Lebs.

Translator’s Prize (presented every two years, and about which I posted recently): Alison Entrekin.

Special Award: Bherouz Boochani’s No friend but the mountains (translated by Omid Tofighian). This award is not made every year, and is often made to a person, but this year it went to a work “that is not readily covered by the existing Awards categories”. The judges stated that it

Special Award: Bherouz Boochani’s No friend but the mountains (translated by Omid Tofighian). This award is not made every year, and is often made to a person, but this year it went to a work “that is not readily covered by the existing Awards categories”. The judges stated that it

demonstrates the power of literature in the face of tremendous adversity. It adds a vital voice to Australian social and political consciousness, and deserves to be recognised for its contribution to Australian cultural life.

Some of you may remember that I recently wrote about taking part in a reading marathon of this book.

Congratulations to all the winners – and their publishers – not to mention the short- and long-listees. We readers love that you are out there writing away, and sharing your hearts and thoughts with us. Keep it up!

Vale Les Murray

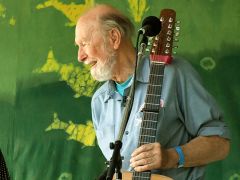

As I said in my intro to this post, I was shocked to hear this evening that one of Australia’s greatest contemporary poets, Les Murray, aka the “Bard of Bunyah”, had died. He was only 80.

His agent of 30 years, Margaret Connolly, confirmed the news, saying that

The body of work that he’s left is just one of the great glories of Australian writing.

I don’t think that’s an exaggeration.

I don’t think that’s an exaggeration.

Black Inc, released a statement saying

Les was frequently hilarious and always his own man.

We mourn his bundles of creativity, as well as his original vision – he would talk with anyone, was endlessly curious and a figure of immense integrity and intelligence.

Although I don’t write a lot about poetry, Les Murray has appeared in this blog before, most particularly when Mr Gums and I attended a poetry reading featuring him. What a thrill that was. He was 75 years old then, and the suggestion was that these readings were probably coming to an end due to his health. I have just two of his around 30 volumes of poetry – The best 100 poems of Les Murray and an author-signed edition of Selected poems, both published by Black Inc – and dip into them every now and then.

His poetry was diverse in form, tone, subject-matter. He could be serious, fun, obscure, accessible. You name it, he wrote it. He was often controversial, being, as Black Inc said, “his own man”! In other words, he was hard to pin down, not easy to put in any box. David Malouf, interviewed for tonight’s news, said that he could be “funny”, he could be “harsh”, but that he said things “we needed to hear”. And that, wouldn’t you say, is the role of a poet, particularly one considered by some to be a candidate for the Nobel Prize for Literature?

If you would like to find out more about him, do check out his website, and if you’d like to read some of his poetry (though it would be better to buy a book!), you can check out the Australian Poetry Library. Lisa ANZLitLovers) has also written a post marking his death.

Meanwhile, I’m going to close with the last lines of a poem called “The dark” in his Selected poems (which he chose in 2017 as his “most successfully realised poems”):

… Dark is like that: all productions.

Almost nothing there is caused, or has results. Dark is all one interior

permitting only inner life. Concealing what will seize it.

Seems appropriate for today.