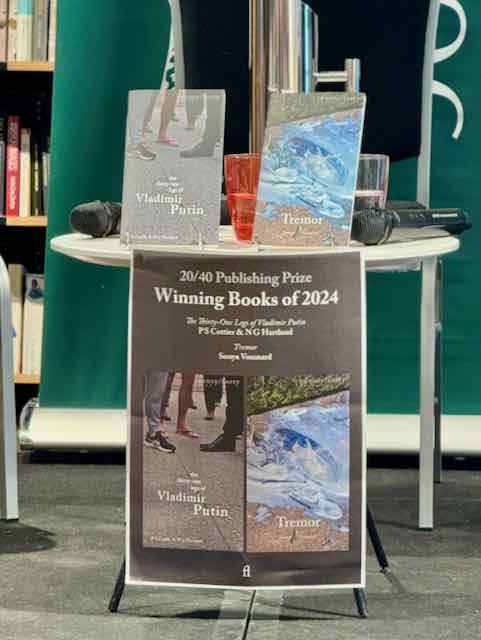

I mentioned the nonfiction winner of the 2024 Finlay Lloyd 20/40 Publishing Prize, in this week’s Monday Musings, but saved the full winner announcement until after I attended the launch at a conversation with the winning authors this weekend.

The participants

This year, as publisher Julian Davies had hoped, there was a prize for fiction and one for nonfiction. The winners were all present at the conversation, and were:

- Sonya Voumard for Tremor, which the judges described as “notable for its compellingly astute interweaving of the author’s personal experience with our broader societal context where people with disabilities, often far more challenging than her own, try to adapt to the implicit expectations and judgements that surround them”.

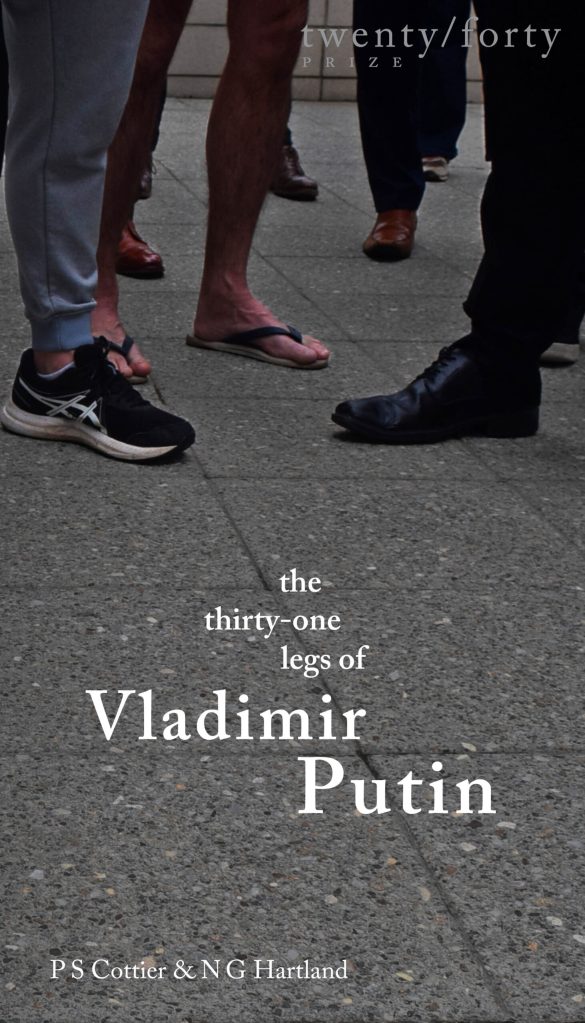

- P S Cottier & N G Hartland for The thirty-one legs of Vladimir Putin, which the judges said “welcomes us to a world where absurdity and reality are increasingly indistinguishable and where questions of identity dominate public discourse. The book spirits us off on a playful journey into the lives of a group of individuals whose physical attributes appear to matter more than who they may be.”

The conversation was led by Sally Pryor who has been a reporter, arts and lifestyle editor, literary editor and features editor at The Canberra Times for many years. Born in Canberra, and the daughter of a newspaper cartoonist, she has a special connection to our city and its arts world.

And of course, the publisher, Julian Davies, started the proceedings. As I wrote in last year’s launch post, he is the inspiring publisher and editor behind Finlay Lloyd, a company he runs with great heart and grace (or so it seems to me from the outside.)

The conversation

Before the conversation started proper, Julian gave some background to the prize, and managed to say something different to what he said last year. He described Finlay Lloyd as a volunteer organisation, with wonderful support from writers like John Clanchy. He reminded us that they are an independent non-profit publisher, but wryly noted that describing themselves as non-profit seems like making virtue out of something that’s inevitable! Nonetheless, he wanted to make clear that they are not a commercial publisher and aim to be “off the treadmill”. And of course he spoke of loving “concision” and the way it can inspire real focus.

As last year, the entries – all manuscripts, as this is a publishing prize – were judged blind to ensure that just the writing is judged. The judging panel, as I wrote in my shortlist post, included last year’s winners.

Then, Sally took over … and, after acknowledging country, said how much, as a journalist, she also loved concision. Short books are her thing and they are having a moment. Just look, she said, at Jessica Au’s Cold enough for snow (my review) and Claire Keegan (see my post). Their books are “exquisite”. She then briefly introduced the two books and their authors. Sonya’s Tremor is a personal history told through vignettes, but which also explores more broadly the issue of viewing differences in other. She then jokingly said that she “thinks” Nick and Penelope’s book is fiction. Seriously though, she loved the novel’s set up which concerns the lives of 16 Putin “doubles”. It’s a page-turner. The books are very different, but share some themes, including identity, one’s place in the world, and how we can be captured and defined by the systems within which we live.

On Sonya’s journey

The conversation started with Sonya talking about her journey in writing this book. She was about to have brain surgery, a stressful situation. But she’s a journalist, and what do journalists do in such situations? They get out their notebook. Her coping mechanism was to cover it as a story, one of big stories of her life.

She has had a condition called Dystonia – mainly tremor in her hands – since she was 13. She managed for many years but, as she got older, more manifestations developed, not all easily linked to the condition, and her tremor got worse. Getting it all diagnosed took some time.

Sally noted that in the book, the doctor is thrilled that he could diagnose her and have someone else to observe with this condition (which is both environmental and genetic in cause). Sonya, of course, was thrilled to have an answer.

On Nick and Penelope’s inspiration and process

It started when they were holidaying in Queensland. I’m not sure I got the exact order here, but it included Penelope’s having read about Putin doubles, and Nick having been teased about looking like Putin. Penelope said it was a delight to write in a situation where humour would not be seen as a negative. The story is about look-alikes being recruited from around the world to act as Putin doubles should they be so needed.

Sally commented that the doubles respond differently. For some, it provides purpose, while others feel they lose their identity. What’s their place in the world, what does it mean?

Putin, said Nick, is an extraordinary leader who has morphed several times through his career. They tried to capture different aspects of him, though uppermost at the moment is authoritarianism. How do we relate to that? Penelope added that it’s also about ordinary people who are caught up in politics whether we like it or not. Capitalism will monetise anything, even something genetic like your looks.

Sally wondered about whether people do use doubles. Nick and Penelope responded that it is reported that there are Putin doubles – and even if they are simply conspiracy theories, they make a good story.

Regarding their collaborative writing process, Nick started “pushing through some Putins” so Penelope wrote some too, but they edited together. Nick is better at plot, at getting a narrative arc, Penelope said.

On Sonya’s choosing short form not memoir

It was a circuitous process. There is the assumption that to be marketable you need to write 55,000 plus words. She had the bones, and then started filling it out, but it was just “flab”. The competition (and later Julian) taught her that there was a good “muscular story” in there, so she set about “decluttering”. Sally likes decluttering. The reader never knows what you left out!

“Emotional nakedness” was a challenge for her, and to some degree members of her family found it hard being exposed – even if it was positive – but they learnt things about her experience they hadn’t known. Sonya’s main wish is that her family and loved ones like what she’s written.

But, did she also have a sense of helping others? Yes! There are 800,000 Australians with some sort of movement disorder, and many like she had done, try to cover it up. (For example, she’d sit on her hands during interviews, or not accept a glass of water). Her book could be liberating for people.

Continuing this theme, Sally suggested there are two kinds of people, those who ask (often forthrightly) about someone’s obvious condition, and those who would never. She wondered how Sonya felt about the former. It varies a bit, Sonya replied, but it feels intrusive from people you don’t know well. At work it can feel like your ability is being questioned.

On Nick and Penelope’s editing process

Nick explained that their story had a natural boundary, given they had a set number of Putins. (And they didn’t kill any Putin off in the writing!) There was, however, a lot of editing in getting the voice/s right, and getting little arcs to the stories.

In terms of research, they read biographies of Putin, and researched the countries their Putins come from.

Sally wondered whether Nick and Penelope saw any legal ramifications. Not really, but they did research their Putins’ names to get them appropriate but unique, and they have a fiction disclaimer at the end (though Julian didn’t believe it necessary!)

On Sonya’s writing another book on the subject, and on negotiating with those involved

While there are leads and rabbit holes that could be followed, Sonya is done with this story (at present anyhow).

As for the family, Sonya waited until the book was finished to show them, but she also tried to avoid anything that might be hurtful or invade people’s privacy. She’s lucky to have a family which has tolerated and understood the journalistic gene. Regarding work colleagues, she did talk to those involved. It was a bit of a risk but she didn’t name those who had been negative towards her. Most people just thought her shaking was part of her, and she liked that.

Sally talked about the stress of being a daily newspaper journalist, with which Sonya agreed, and gave a little of her personal background. She started a cadetship straight out of school and was immediately thrust into accidents and court cases. It was a brutal baptism. Around the age of 30, when the tremor and other physical manifestation increased, she decided she couldn’t keep doing this work.

Were they all proud of their achievement with this format?

As a poet Penelope is comfortable with brevity, so this was an expansion (to sentences!) not a contraction. Nick was obsessed with “patterning” – with ordering, moving between light and dark, internal and external, providing an arc. Penelope added that it started with less of an arc, including no names for the Putin doubles.

Sonya paid tribute to Julian for being “such an amazing editor” who taught her about how to impose structure on chaos. Penelope added that it was an intense editing process. It was also a challenge because, being a publishing prize it’s not announced until publication so she couldn’t tell people what she was working on. But the editing process was interesting.

Q & A

There was a brief Q & A, but mostly Sally continued her questions. However, the Q&A did bring this:

Is Nick and Penelope’s book being translated into Russian and/or will it be sent to Putin: Julian said Finlay Lloyd were challenged enough getting books to Australians. Penelope, though, would love Russians having the opportunity to read it. Perhaps, said an audience member, it could be given to the Russian embassy …

Julian concluded that it had been a joy working with these authors who “put up with him”, and thanked Sally sincerely for leading the conversation.

This was a lovely warm-hearted event, which was attended by local Canberra writers (including Sara St Vincent Welch, Kaaron Warren, and John Clanchy) and readers!

These books would be great for Novellas in November. You can order them here.

The Finlay Lloyd 20/40 Publishing Prize Winning Books of 2024 Launch

Harry Hartog Booksellers, Kambri Centre, ANU

Saturday, 2 November, 12.30-1.30pm