‘Of course we are mad,’ Bet wrote to Mary, ‘but we live in a mad place.’

The mad place that Bet – Elizabeth Durack – refers to is the Kimberley region of north-west Australia and the book this quote comes from is biographer Brenda Niall‘s True north: The story of Mary and Elizabeth Durack.

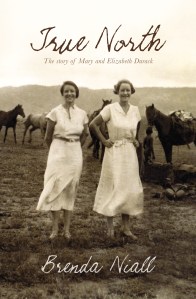

Brenda Niall, along with the late Hazel Rowley, is one of Australia’s best regarded biographers. True North, her most recent book, tells the story of writer Mary Durack (1913-1994) and her younger sister, the artist Elizabeth (1915-2000). I must say that it took me a long time to read this book. I was fascinated by the story but it lacked, in the beginning at least, some of the punch that I found in Rowley’s Franklin and Eleanor: An extraordinary marriage which I reviewed last year. I think this is because Niall’s style here is a little flatter, a little more like reportage, than I found in Rowley’s book. Both books have two people as their subjects and both books have an overriding theme – the Roosevelts’ extraordinary marriage for Rowley and the sisters’ fascination with the remote north for Niall – but, for me, Rowley’s had a stronger narrative drive which resulted in a more cohesive “argument”. However, I did settle into True North and, in the end, enjoyed it for what it did do.

Mary and Elizabeth, for those of you who don’t know, belonged to the pioneer pastoralists, the Duracks, who had emigrated from Ireland in the 1850s. They farmed in Goulburn (NSW), then moved to Coopers Creek (Queensland) in the late 1860s, before droving their cattle nearly 5,000 kms cross-country to settle in the Kimberleys (WA) in 1882. Mary told this story in her best-selling (now classic) history, Kings in grass castles, and its sequel Sons in the saddles.

Niall’s book, though, is not about that, but about the two sisters and their lives in the 20th century. Mary and Elizabeth spent most of their childhood and youth in Perth, while their father managed the northern properties, returning south each year in the off-season. However, both separately and together spent time on their father’s properties, particularly in their late teens and early twenties. Niall’s title, “true north”, expresses the sisters’ identification with the north. In 1929, for example, Mary said she returned to the north “like a homing pigeon”. Elizabeth described it, a few years later, as “that wild, wonderful country”. The north was, in fact, the inspiration for their creative output.

Niall characterises the two sisters well. Mary was the calmer, more sociable, reliable one who struggled to find time to write between raising children, supporting various family members, and playing a significant role in the literary life of Perth. Elizabeth was more unsettled, more fiery and perhaps more ambitious. She was frequently poor and depended on the family, particularly Mary, for monetary and emotional support throughout much of her life. Theirs was a close relationship, and included several collaborative books for which Mary wrote the text and Elizabeth did the illustrations. Neither made wonderfully successful marriages – and both, despite their challenges, produced significant bodies of work.

Several themes run through the book, but the most interesting one for me concerns the Duracks’ relationship with Aboriginal people. From early on the family employed indigenous people. According to Niall, the sisters’ father, Michael Patsy Durack, “stressed their value as allies”. For the sisters, their early experiences were positive and resulted in a lifelong interest in and awareness of indigenous people and their issues. Elizabeth spoke many years later about “how lovely it was to go walking with them and to learn about the bush” while Mary wrote of being disturbed by “the shadow people in their humpies on the river banks, humbly serving, unknowing, unquestioning”. Mary wrote a short story, “Old Woman”, about the harsh treatment of an Aboriginal woman by a station wife. It was published in The Bulletin in 1939 and nearly resulted in a libel suit. Elizabeth wrote in a letter, around 1935,

It’s a question of either opening one’s eyes to the situation and grappling with it with whatever instruments lie within one’s reach or shutting one’s eyes to the whole business and getting the hell out of it.

I don’t have time to fully explore it all now, but I was intrigued by this comment on Mary late in her life:

She found the Aborigines surprisingly objective about the past ‘recalling events with no hint of bitterness’, talking about the white people with neither praise nor blame.’

This brought to mind indigenous writer Kim Scott’s That deadman dance, which I reviewed last year and in which he presents (albeit in a novel but borne out by the records, I believe) a similar generosity or openness of spirit. But, back to True north. Niall argues that the Duracks were respectful and sympathetic employers and friends. Big brother Reg in the 1930s was aware of “the social injustice of use of Aboriginal labour”. Mary, in the 1960s, argued persistently for equal pay, and even though, when it came, indigenous station workers were displaced in droves, she still believed in the principle. Ah, that tricky conundrum: principle versus reality, idealism versus pragmatism. Why are they so often at loggerheads with each other?

Elizabeth, however, did get into hot water later in her life when, going way further than Mary who wrote a poem in the voice of an indigenous woman, she took on the name and persona of an Aboriginal man, Eddie Burrup, as a nom de brush. Niall discusses the issue at some length teasing out artistic and personal issues versus cultural trespass. She is sympathetic in the end to Durack and her somewhat mixed motivations. The situation was certainly complicated and, while some of Durack’s motivations give me pause, I’d rather not pass judgement, except to say that in the late 20th century it was not a wise thing to do.

The insight Niall gives into an albeit specific pastoral family’s experience of and response to their relationship with indigenous people makes this book worth reading. We do of course only get Niall’s presentation of the Duracks’ experience. Besides a few scattered references to indigenous people’s responses, we know little of the indigenous perspective. The sad thing is that we may never know their side, since few people are left to tell it, and not much is likely to have been documented.

Oh dear, I’ve written a lot about one theme and there’s so much more to tell, but I won’t retain you much longer. Two other major themes permeate the book. One revolves around love of and identification with place, with how place can get under the skin and drive one’s life. The other concerns the challenge women creators face in serving their art while juggling families and the need for financial support.

While I didn’t find Niall’s book as compelling as I’d hoped, the more I think about it, the more I appreciate what she has attempted to do. The Duracks’ story is a complex and somewhat contradictory one. Mary, Elizabeth and their brothers were the children of a “cattle king”, and being such their public image was “one of effortless privilege”. The reality was, in fact, rather different – and it resulted in lives that were challenged and challenging. Niall’s book will not, I suspect, be the last we hear of them – but it makes a valuable contribution.

Brenda Niall

True North: The story of Mary and Elizabeth Durack

Melbourne: Text Publishing, 2012

Kindle edition

272pp (Print ed.)

ISBN: 9781921921421 (eBook)