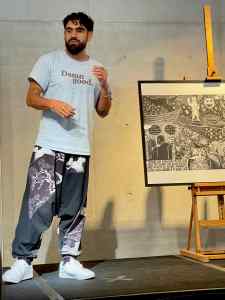

The Canberra launch of Irma Gold’s latest book, her second novel Shift (my review), was a joyful affair that reminded me of other launches of books by Canberra writers, such as Karen Viggers’ Sidelines and Nigel Featherstone’s My heart is a little wild thing. Canberra is a comparatively small jurisdiction so when one of our own launches a book, local authors, booksellers, publishers, editors, critics, reviewers and readers turn out to cheer them on. Such was the case tonight when Irma Gold came to town to launch Shift. She now lives in Naarm/Melbourne, but was active in the Canberra literary community for over a decade.

Both Irma Gold and Karen Viggers have appeared many times in my blog, so I won’t introduce them again, but I will remind you that they now jointly produce the Secrets from the Green Room podcast. They are clearly simpatico, and the conversation, as a result, flowed easily while still covering meaningful ground.

The conversation

Karen commenced with an acknowledgement of country and a rundown of Irma’s many achievements, and then led into the conversation with a cheeky question …

Had the several outstanding reviews she’d received in the first month after publication gone to her head? It has been a dream response, admitted Irma, but what means most to her are the supportive messages she’s received from her friends in Soweto.

Karen then briefly summarised the book. It’s about portrait photographer Arlie who goes to Kliptown, in Soweto, partly because his South African mother refuses to talk about it. The sensitive and somewhat lost Arlie needs to know more, to understand his mother, and, he’d like to prove himself to his father. Karen said she found the ending deeply moving.

Why South Africa? Irma’s father was born there, so she’s always been interested. This was further sparked in her teens when she read Biko, resulting in her reading more about freedom fighters and South Africa more widely. She didn’t get to South Africa until her 40s, when she went with her youngest brother. Through a chance meeting, they were introduced to Kliptown, a community with no electricity, school or sewerage, among other things. A seed was sown then. She visited again, with another brother (a trip which I followed through Irma’s Instagram account. It was fascinating, if I can use such a shallow-sounding word for such a poorly supported community.) Karen then asked how dangerous it was. Irma felt safer in Kliptown, despite its reputation for violence, than in other parts of South Africa, mainly because she and her brother were working in and for the community.

On the haves vs have-nots. Karen spoke of how well Irma had illustrated the gap between the haves and have-nots; how she’d shown Arlie displaying his privilege without always being aware of it, while other times he’d catch, and be embarrassed by, his stumbles in this regard. Irma shared an anecdote about giving money to someone who had been their guide, and the difference it had made for him. She felt guilty all the time. As she was writing the novel she reflected constantly on how, by virtue of birth, she lives here in privilege and they live there.

On creating a great sense of place. Irma kept notebooks, and took lots of phots and videos. Watching the videos would take her right back there, and she’d remember more including things she hadn’t written down. People didn’t mind her taking photos. In fact they loved it, but she was working with the community.

On the characters and their names. Irma has no idea where Arlie came from. He was in her head when she made her first trip to South Africa. Also, she didn’t specifically choose photography for him but in retrospect, she realises it’s the perfect choice, because photography is all about different ways of seeing things. She’s always loved photography, but she did have expert advice from a photographer in the Canberra writing community. Jigs, Arlie’s brother’s fiancee, also just came to her, but the spark for Glory came from seeing a gorgeous young woman in a local gospel group. As for her African characters’ lively names, many of the Africans she met know what their names mean, why they were given their names. Being an “over-sharer” herself, she loves their openness and willingness to tell their stories.

On Mandela. Irma was shocked to find that Mandela was not the hero in young Africans’ eyes as he was in hers. They feel they’ve been sold a “broken dream”, that things have not improved as they were promised. Bob Nameng of SKY (Soweto Kliptown Youth) kept telling her that she had to write about the situation because no one is listening, nothing changes. This is not to say that Kliptown is all tragedy. There is also a lot of joy. She saw so much art and music in the community, and an overall “lust for life”.

On relationships. Karen was particularly interested in what Irma was trying to show in Arlie’s difficult relationship with his father. Irma said that Arlie judges his father harshly, but Glory suggests to him other ways of looking at the situation. Forgiveness and openness are important in relationships.

What is she asking of her readers? Irma liked the idea that she was “making the invisible visible”. She grew up in a family that had strong feelings about injustice. Ultimately, the book is about people. They are the most important thing to her. Kliptown is its people. She also likes Charlotte Wood’s idea of following “wherever the heat is”.

Q & A

On the title: It was a complicated process. Her original title was either disliked or deemed forgettable. In the end she produced a list, from which the publisher made a selection, and she chose one of those! She now likes her title.

On being published in South Africa. Currently only Australia-New Zealand rights have been sold. It’s difficult getting books into other jurisdictions.

Karen concluded by asking whether there was a “drive for change” in the novel. Although Irma had said that people and relationships are her over-riding interest, she admitted that change is also part of what it is about. Yes! I remember that Irma also said her first novel The breaking was primarily about the relationships. However, it too is about an issue – elephant tourism – that she would like to see changed. The way I see it is that her novels are inspired by justice-related issues that she would like to see changed, but that relationships are what fascinate her. In truth, you probably can’t solve big issues without having good relationships. Combining a passion for driving change and for good relationships between people makes, I’d argue, for good reading.

Thanks

The evening concluded with Irma thanking many in the Canberra community who had helped her, including of course Karen Viggers, but also John Clanchy who had read many drafts and whose honest feedback was instrumental in the book’s coming into being, Dylan Jones for being her photography consultant, the wonderfully supportive Canberra writing community, ArtsACT for helping her with some funding (again), and the Street Theatre for hosting the event.

Irma Gold – Shift: Book Launch

The Street Theatre, Canberra

9 April 2025

Louise Allan

Louise Allan Amanda Curtin

Amanda Curtin Nigel Featherstone

Nigel Featherstone

Michelle Scott Tucker

Michelle Scott Tucker