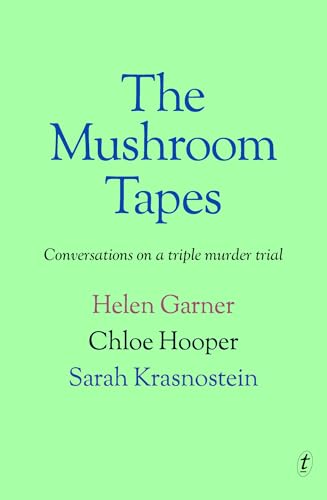

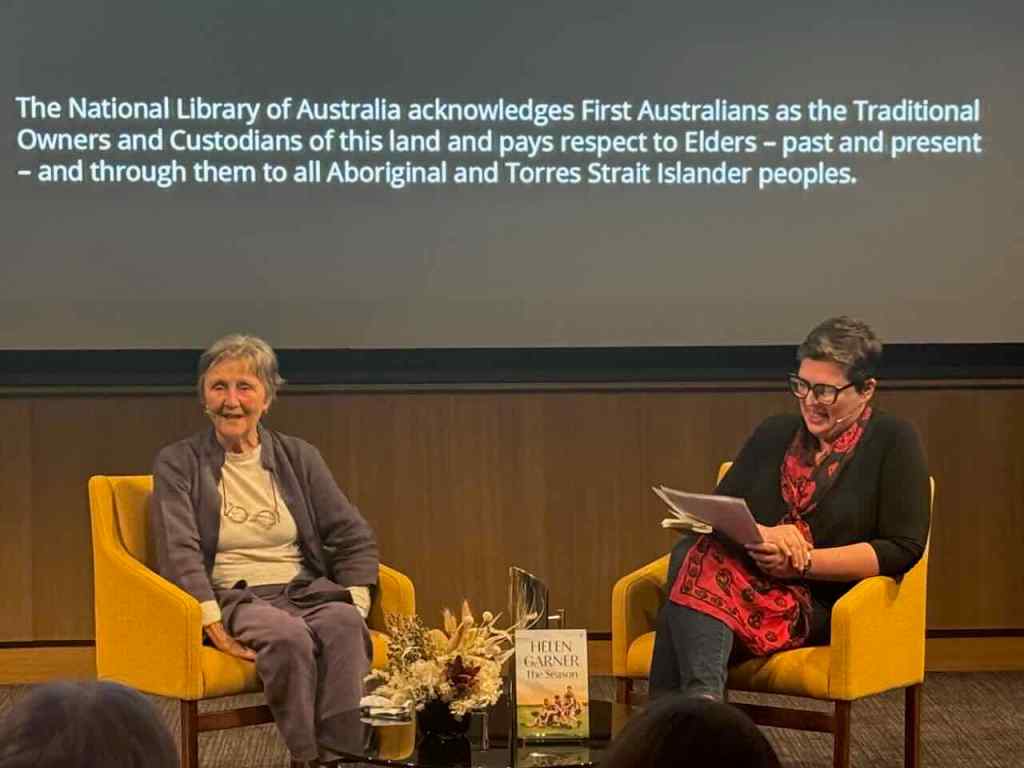

Last night’s ANU/Meet-the-Author event was a sold-out affair, in a 500-seat theatre. And why not? Helen Garner, Chloe Hooper, and Sarah Krasnostein are among Australia’s top writers of narrative nonfiction, and they have just produced a book about the Leongatha mushroom murders. Indeed, it’s only because they have written about it that I am interested in reading about this case. Of course I knew about it, but I didn’t follow it intensely because these tragic criminal cases that capture the public’s attention so often become unedifying spectacles in which emotion overtakes reason in much of the public discourse. And I don’t want to go there.

As always, Colin Steele did the introductions, including explaining that Chloe Hooper had had to pull out due to her young son being sick. He referenced Jen Webb’s recent article on The mushroom tapes in The Conversation, and quoted her statement that “If I were asked to pick three people to write about this dramatic, yet banal, crime story, I’d choose them”. Yes! He then handed the floor over to Beejay Silcox.

The conversation

I was disappointed not to see Chloe Hooper because I have seen Helen and Sarah in action before, and because Kate (booksaremyfavouriteandbest) loved the event she attended with the three of them. So, Chloe’s absence created a significant hole, but Helen and Sarah filled it wonderfully – and graciously. They were open, thoughtful, and, as Kate found, still discovering new things to talk about.

Beejay started by quoting Janet Malcolm, who, she clearly knows, is a favourite of Garner’s. Malcom has argued that what journalists do is “morally indefensible” because of the way they draw in and then report on their subjects. But, continued Beejay, good journalists will overcome this risk by not rushing in, by, I think she said, applying “a tilt” to the way they look at things. And these writers are “masters of the tilt”.

On working together

The conversation covered the sorts of things you would expect for a book like this, including our complicity as readers/spectators, why this case, the need to resist easy answers, their process, their thoughts on the trial, and where the trust in each other had come in.

Sarah noted that there is no division between Helen’s work and her person, which of course is what so many of us love about her, but which has also brought her criticism. They all respected each other – not surprisingly – so had no doubts about each other’s personal processes. Helen said they were like people who had been in and survived a car crash. They were friends for life now.

Beejay referred to the fact that each had shared what their opening line would have been had they written the book alone (though they wouldn’t have, they said). Their lines (pp. 4-5) capture something about their individual approaches. Helen’s, which plays on lines by Sir Walter Scott, sounds baroque, Shakespearean. It speaks of empathy and the question of where is the line that an ordinary person crosses to commit such a crime. Chloe’s is more sociological (as in, what in society created this), while Sarah’s is more legal. As Sarah said, each had her own tone and vibe, her own interest in what they were observing.

Sarah commented on how the case had “asserted itself into public discourse with velocity”.

There was more talk about how and why they decided to write this book. They admitted to bristling at the assumption from others that it was “their story”. They found the sensationalism repellent. (In a humorous interaction, Helen dobbed Sarah and Chloe in as readers of the Daily Mail, which she eschews, but didn’t mind their passing on its news!)

It was an exhausting process, given the trial lasted 10 weeks. Helen talked of how you cope with something like this, on defending yourself against awfulness and pain of the trial, how the mind turns off. They noticed early that the journalists had formed a gang, presumably their way of coping. Beejay suggested that humour is another way, and that Helen provided some of the book’s comic relief.

On the court – and their approach to understanding it

The court is a workplace, said Sarah, so alongside extraordinary grief and distress are all the administrative aspects, such as when to have lunch, managing a juror needing a toilet break. They shared examples of humour and drama in the witness box. Sarah described their work as an “ethnography of a micro-world”, one in which they tried to capture the humanity of court.

Observing that their book is more about watching, than about the judgement, Beejay asked what was important to see, that we normally wouldn’t. Helen’s answer came quickly. It was distress and suffering. You see the survivors. Helen said they dreaded people thinking they were taking suffering lightly. Sarah agreed, adding that one of the heaviest things is that this is not a story of exceptionalism but more of “there but for the grace of god …”

They talked about emotions versus the banality, the quotidian details, such as, for Helen, Erin’s toe in the hiking sandals she would wear. She commented on being nearly undone by the domestic nature of it all, such as survivor Ian talking about having “a nice bowl of porridge” in the morning with his wife of many years, and now she’s gone.

Beejay described the book as both spectacle and literature, and quoted Helen’s comment in it that “everything could become a metaphor here“. The discussion went roundabout here, but essentially they agreed that in a case like this, metaphor must be handled carefully. In fact, Helen suggested that the urge to get metaphorical doesn’t belong in nonfiction. Sarah shared something from documentary filmmaker Ken Burns. He said that to find a detail that stands for the whole is a gold nugget, but then realised that that detail (from his Vietnam War film) represented the piece of a man’s soul that had come at great cost – so “gold nugget” was not appropriate. So, said Sarah, you must handle metaphor carefully, as you are dealing with human meaning. Helen had never heard Sarah say this. They agreed that nonfiction deals with facts you must honour, that it is chained to reality in a certain way.

On Erin

This led to a conversation about Erin, how the public had turned her into “a character”, and how information that had come up in the pre-hearings (such as probable earlier attempts on her husband’s life) was deemed inadmissible in court because there was no evidence. This decision would enrage a family, Sarah said, but is necessary to protect the presumption of innocence. (There was humour in the conversation here because Daily Mail readers knew this information, but Helen didn’t – and had felt an idiot!)

But, who was Erin? Mostly, women kill to protect, so Sarah had gone into the hearings with this understanding, but as information came out she had to reassess her thinking.

Helen found Erin a strange person, but thought the court artists’ depiction of her as evil, witch-like, was appalling. Later, they described the way the media/the public feasted on her was a form of horror.

Sarah said that when Erin started speaking on the witness stand, she was articulate, funny, recognisable, but gradually, as she was questioned, this picture melted. It was hard to separate Erin’s self from the persona. The unpalatable parts of her personality were on display. The bad-tempered teacher-like tone she used in response to the prosecutor was a misstep. It’s a middle-class story, said Helen.

Re explaining Erin’s crossing that line into murder, Helen was surprised to find that the prosecution doesn’t have to find a motive. She doesn’t have an answer. Like most humans, Erin embodied various people, mother, crabby teacher … Sarah added that Erin is not legally insane but is a deeply disordered person, so how do you apply “order” to her? We want answers, but we can often be mysterious to ourselves. Erin is recognisable as a mother, but like many of us can also harbour a primal rage.

Q & A

On how such an intelligent, well-educated woman could think she could get away with it: Helen has a theory about murderers. They have a great desire to do it, and a fantasy about how they are going to do it, but this all stops at the lethal blow because they haven’t thought about what happens next. So, for example, Erin hadn’t concealed evidence of her ownership of the dehydrator. This was astonishing,

On ethical issues they considered during the process: There were many, including the children, the community, whether they should look at sites (like the home). Are you adding to harm or does not looking do harm too? They questioned whether they were looking out of human curiosity, were they just perving? Sarah said that Helen has a view about “utility”. Courts are public, so we should understand them, we should ask questions about what they are doing. Hannah Arrendt described such crimes or behaviour as “a rent in the social fabric”. The law is being acted in our name, so we have duty to know what the law is doing. Part of the “utility” is to add complexity to our understanding, to show that the law, and these cases, are not simple.

On the role of gender in how the case played out publicly: Gender absolutely played a role. Had the crime been committed by a man it would not have held the public’s attention for so long. This was a middle class mum, set around something domestic, the serving of a meal. Her behaviour was a violent inversion of a major archetype of what women are. The gleeful mocking tone employed by some commentators was an insult to victims. (And reminiscent of how Lindy Chamberlain was “feasted upon”.)

Finally…

Beejay described the book as “a love letter to doubt”, to which Helen responded that she is a fan of ambivalence. Yes! She is not the god of all knowing consciousness; she wants readers to be there, questioning along with her. Doubt comes in different forms. At times, Helen and Sarah would be sentimental and mushy, while Chloe would remonstrate, “Guys, she’s planning to poison them”. They agreed that their essential subject matter was the preservation of doubt.

Beejay concluded by asking them what they wished we all knew or felt. Sarah named the mockery, caricature, parody that was applied to the case. Why do people do this? These are people’s lives, and it affected a family and an entire community. Helen agreed, adding that “you want to preserve the tenderness in the story”. The old people who died kept disappearing from the story, but they were plain country people with faces of kindness, people who had helped Erin in need (which she recognised).

So, another excellent conversation with some meaningful takeaways encompassing how we respond to crimes like this, how we value writers who bring them to us in a considered thoughtful way, and how doubt and acknowledging complexity should be our mantras.

ANU/The Canberra Times Meet the Author

MC: Colin Steele

Lowitja O’Donoghue Cultural Centre, Australian National University

19 November 2025

Helen Garner

Helen Garner