Earlier this year I posted on Thomas King’s short story “Borders” from Bob Blaisdell’s anthology, Great short stories by contemporary Native American writers. The story was written in 1991, but as I noted in my post, it has also been adapted into a teleplay for the CBC, and turned into a graphic novel for younger readers. I was intrigued, and because I loved the story, I bought the graphic novel, on the assumption that we will share it with our grandchildren in a few years.

To recap a little from my original post. Wikipedia describes King as an “American-born Canadian writer and broadcast presenter who most often writes about First Nations”. Born in California in 1943, he “self-identifies as being of Cherokee, Greek, and German descent”, and has written novels, children’s books, and short stories. I also shared from Wikipedia a quote they include from King’s book, The inconvenient Indian, because it’s relevant to Borders:

“The issue has always been land. It will always be land, until there isn’t a square foot of land left in North America that is controlled by Native people”.

In that post I summarised the story, and I’ll repeat that here too. The narrative comprises two alternating storylines, both of which are told first person through the eyes of a young boy. One storyline concerns his much older sister, Laetitia, leaving home at the age of 17 to live in Salt Lake City, Utah, while the other tells of a trip he makes with his mother some five or so years later to visit this sister.

The crux of the story lies in what happens at the US-Canada border. Asked to give her “citizenship”, the mother insists “Blackfoot” and is denied entry. She refuses to offer anything else. As a result, she and her son get caught in a no-man’s land when, attempting to return to Canada, the same response to the same question results in her being refused entry there too. As one of the border officials tries to explain to her, “it’s a legal technicality, that’s all”. Of course, that’s not all. Blackfoot people ranged across the great northwest of America in what is now known as America and Canada. For our narrator’s mother, that land is her “citizenship”, not that she is American or Canadian, and she will not back down.

So, to the graphic novel. The illustrator is Natasha Donovan, who is described at the back of the book as “a Métis illustrator, originally from Vancouver, Canada”. She has illustrated, among other books, “the award-winning graphic novel Surviving the city, as well as the award-winning Mothers of Xsan children’s book series.”

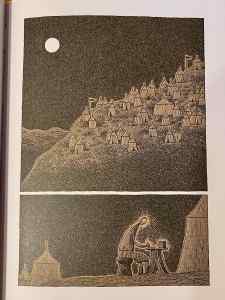

This graphic novel version of Borders is beautiful. It turns what is a perfectly suitable story for pre-adult readers into a book that should appeal to and engage these readers. It contains King’s full text as far as I can tell, enhanced (if I can use that word) with Donovan’s gorgeous drawings. Because it is designed for younger readers, the drawings are simple enough to appeal to younger readers, but they offer a subtle depth which make the story well worth reading in this form by older readers too. The original story is told in a spare style, which leaves the reader to imagine (work out) the ideas and emotions behind the words. In this graphic version, sometimes the illustrations replicate the words, but in many cases they value add. This is not to say that value-adding is necessary, as it’s a gem of a story, but that the drawings encourage the reader to stop, think, and consider what the words might be saying.

An example: of their second night stuck in border-limbo, our narrator says that “The second night in the car was not as much fun as the first, but my mother seemed in good spirits and, all in all, it was as much an adventure as an inconvenience”. The panel following this depicts chicken wire in the foreground with a flock of birds flying off in the background, conveying some of the tension between the constraint of borders and the idea of freedom. The next panel, also textless, shows mother and son companionably sitting on the boot of their car, eating their sandwiches. In the border-guard scenes, the narrator mentions their guns. Donovan picks this up, providing frequent close-ups of guns, gun belts and holsters when the guards are present, which suggests authority and, perhaps, menace without overplaying the idea of fear.

What I liked about this graphic version, too, is how much it encouraged me to “see” things from our young protagonist’s perspective. I saw it in the text, but it becomes more vivid and immediate in this version. We see him report what he is seeing, and his own thoughts; we see him inserting his boy-ish wishes and perspectives. There is a running theme, from the beginning, about food which marks his focus on the concrete, on his needs. He asks Mel, the duty-free shopkeeper, for a hamburger, which he doesn’t get, but the next day:

Mel came over and gave us a bag of peanut brittle and told us that justice was a damn hard thing to get, but that we shouldn’t give up.

I would have preferred lemon drops, but it was nice of Mel anyway.

In this way, King conveys the truth as experienced by our young boy, but the wider truth that is happening around him – the strength of the mother’s identity and her determination to preserve it. Occasionally, our young narrator perceives some of these truths too. He sees the pride – and yes, the not always positive stubbornness – displayed by his mother and sister, but concludes:

Pride is a good thing to have, you know. Laetitia had a lot of pride, and so did my mother. I figured that someday I’d have it too.

Hachette’s promo for the graphic novel version describes it as resonating “with themes of identity, justice, and belonging”. It is exactly that – and conveys so much that is both personal and political, making it a rich book for any age to think about and consider.

Thomas King (story) and Natasha Donovan (Illustrator)

Borders (text from the 1993 published version)

New York and Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 2021

[192pp.]

ISBN: 9780316593052