A regular part of my Jane Austen group’s monthly meeting is a show-and-tell which means of course that we share anything new we’ve acquired, seen or heard about relating to Jane Austen. At our February meeting, a member brought along a first edition (I think) of a book a friend had given him as a result of that friend’s downsizing. It pays to have your friends know your enthusiasms!

The book was G.E. Mitton’s Jane Austen and her times, 1775-1817 (1st ed. 1905). We were intrigued as none of us had heard of this book or its author. Who is Mitton? The assumption from some in the group was male, but others of us were not so sure – and we were right to be, because G.E. Mitton is Geraldine Edith Mitton (1868-1955). She was, according to Wikipedia which cites Who’s who from 1907, “an English novelist, biographer, editor, and guide-book writer”.

Wikipedia provides a brief biography for her – drawn primarily from a couple of obituaries – followed by a list of works. It’s not much, but provides some background. She was born in Bishop Auckland, Country Durham, the third daughter of Rev. Henry Arthur Mitton, who was a master of Sherburn Hospital. In her late twenties, Mitton moved to London, where in 1899 she was employed by the publishing company A & C Black, and worked on the editorial staff of Who’s who. In 1920, she became the third wife of colonial administrator Sir George Scott and collaborated with him on several novels set in Burma. (Wikipedia lists four collaborative novels.) Her biography of him, Scott of the Shan Hills (1936), was published the year after his death. Several of her books are available at Project Gutenberg.

I could research her further, and, who knows, I might one day, but she’s not the main point of this post. What I want to share is how she starts her book. Chapter 1 is titled “Preliminary and Discursive”, and it opens with:

Of Jane Austen’s life there is little to tell, and that little has been told more than once by writers whose relationship to her made them competent to do so. It is impossible to make even microscopic additions to the sum-total of the facts already known of that simple biography, and if by chance a few more original letters were discovered they could hardly alter the case, for in truth of her it may be said, “Story there is none to tell, sir.” To the very pertinent question which naturally follows, reply may thus be given.

Little did Mitton know! Despite the significant gaps in her biography, Austen is surely up there as a biographer’s subject. There have been many traditional biographies, including, in alphabetical order, those by David Cecil, yasmine Gooneratne, Park Honan, Elizabeth Jenkins, David Nokes, Carol Shield and Claire Tomalin. But, perhaps partly because of the gaps and partly because books about Austen are popular (and presumably sell well), her life has been written about from almost every imaginable angle, such as:

- through the places she lived (Lucy Worsley’s Jane Austen at home) and the objects she owned (Paula Byrne’s The real Jane Austen: A life in small things);

- through her beliefs and values (Helen Kelly’s Jane Austen: The secret radical and Paula Hollingworth’s The spirituality of Jane Austen);

- through her relationships (E.J. Clery’s Jane Austen: The banker’s sister, Irene Collins’ Jane Austen: The parson’s daughter and Jon Spence’s “imagined biography” Becoming Jane Austen);

- through (or by) her fans (Constance Hill’s Jane Austen: Her homes and her friends); and

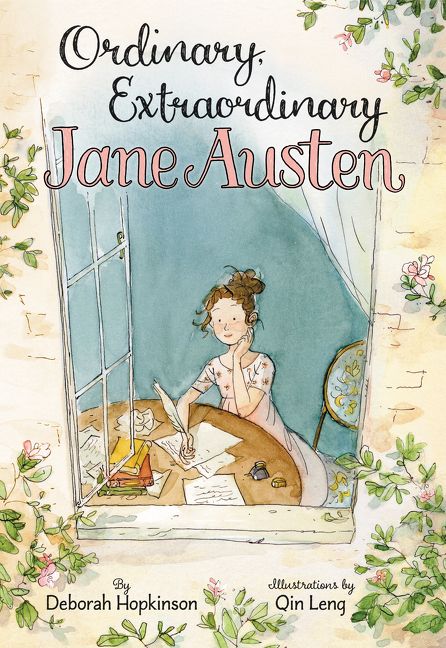

- for children (such as Deborah Hopkinson and Qin Leng’s picture book biography, Ordinary, extraordinary Jane Austen: The story of six novels, three notebooks, a writing box and one clever girl).

Need I continue?

But all that’s an aside. The opening paragraph then continues, and here is the main point of my post:

Jane Austen stands absolutely alone, unapproached, in a quality in which women are usually supposed to be deficient, a humorous and brilliant insight into the foibles of human nature, and a strong sense of the ludicrous. As a writer in The Times (November 25, 1904) neatly puts it, “Of its kind the comedy of Jane Austen is incomparable. It is utterly merciless. Prancing victims of their illusions, her men and women are utterly bare to our understanding, and their gyrations are irresistibly comic.”

Remember, this was written in 1905. Austen may not stand “absolutely alone” – and I would hope that women are no longer seen as “deficient” – in having “a humorous and brilliant insight into the foibles of human nature, and a strong sense of the ludicrous”, but I appreciate Mitton’s recognition of her wit. And that last sentence from The Times is close to perfect.

My Jane Austen group plans to discuss this subject later in the year, so you might see more on this topic, particularly regarding whether we see her comedy as “utterly merciless”. Meanwhile, you are more than welcome to share your thoughts.