And now for something completely different. If Griffyn Ensemble’s last concert, Do you believe? (my review), kept us on our intellectual toes from go to whoa, their third concert* of 2014, House on Fire, had our toes-a-tapping and feet-a-walking in a program that owed more to folk traditions than classical. Collaborating this time with Canberra pop-duo The Cashews (Alison Procter and Pete Lyons), they presented “a new program of original music” composed by them and The Cashews. The programme was inspired by Arthur Boyd’s imaginative, surreal exploration of “place and identity” and was performed at the National Gallery of Australia’s Gandel Hall to coincide with the Gallery’s Arthur Boyd: Agony and Ecstasy exhibition. Mr Gums and I made a day of it. We visited the exhibition, had lunch overlooking the gorgeous sculpture garden and lake, and then went to the afternoon concert.

When I describe this program as more folk than classical, though, I don’t mean to suggest it was simple. This is the Griffyns after all, and their intent was serious even if the presentation had a lighter – and yes, probably more musically accessible – touch.

The programme opened with an empty stage and the sounds of birds which became more intense as the Griffyns took up their places on the stage and started playing music that sounded like dawn – like birds congregating around a waterhole, as the sun comes up. This segued immediately to the Cashews who performed a beautiful acknowledgement of traditional owners. It was an inspired change from the usual spoken one. “I’ll begin where you began”, they sang, “with connection to this land … I acknowledge you”, concluding with “and pause to acknowledge all that is yours”*. Truly moving.

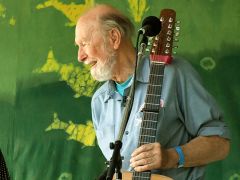

Pete Lyons then introduced the program, and acted as emcee for the rest of the concert. This was interesting given that it was a Griffyn Ensemble concert, but it spoke beautifully to the fact that this was a real collaboration. Lyons told us that the concert would explore such ideas as belonging and unbelonging, connectedness and unconnectedness, metamorphosis, space, landscape, and silence. All of these made sense to an Australian audience, particularly when also viewed through the prism of Arthur Boyd’s complex depiction of landscape and intense relationship with the environment.

I’d love to describe the whole programme but that would take too long. Unfortunately there was no printed program so I can’t list the pieces. In fact I don’t really know the names of them all, but there were 11 or 12 interspersed with commentary, some brief interviews with Griffyn musicians, and a little walk on the outside! The program ran for nearly 2 hours without an interval, but I don’t think anyone cared.

“Moving to a discordant beat”

I did wonder how well the two sets of performers would meld their very different sounds – one folk-pop and the other contemporary classical. I needn’t have worried. These are all seasoned musicians, flexible in their ability and eclectic in their interests. It was particularly interesting to hear Susan Ellis’ classically trained voice mix with Alison Procter’s lighter one. They had (of course) practised and it worked beautifully, invoking for me the way Arthur Boyd had blended so many competing influences and tensions in his work. In several of the pieces of music, this tension was also conveyed by interspersing lyrical sections with more discordant sounds. Surprising how discordant a harp can sound when it tries – and Laura Tanata certainly tried, to great effect.

I enjoyed Holly Downes’ double bass playing in the last concert, and again in this one. Chris Stone produced some gorgeous mournful tones on his violin. A particularly moving piece was the song that expressed the concert’s theme of House on Fire. It drew on Canberra’s tragic bushfire of 2003 and the fire at Arthur Boyd’s childhood home that destroyed his father and renowned potter Merric Boyd’s kiln. The piece opened with Susan Ellis and Laura Tanata, with the whole ensemble then joining in. It conveyed, in words and music, a sense of “moving to a discordant beat”, but also recognised that there is “strength in adversity”.

The Arthur Boyd “theme” played out in various ways throughout the concert. In another piece, “Metamorphosis”, Susan Ellis, in voice, and Holly Downes’ on double bass, led the ensemble in a piece that explored Boyd’s sense of being “out of kilter”. There was a lovely melancholy in the playing here, too, particularly in the opening double bass.

“Listen … I know exactly what I’m looking at”

As always, Kiri Sollis shone with her flute, but we were entertained to discover in one of the little “impromptu” interviews that this concert was a departure for her. Classically-trained Sollis is used, she said, to practising lots to get what’s on the page in front of her right. However, in this show, she didn’t have much on the page in front of her and had to draw on her improvisational skills. She mentioned the sense of liberation and the terror of “not having stuff on the page”, reminding us again of Boyd and his terrors! She, like Boyd, needn’t have worried.

We were informed at the beginning that there would be silence and a walk. The silence occurred around the halfway mark, and was introduced by Pete who talked of Boyd’s silence about his work. We can understand why, agreeing with Pete’s comment that Boyd’s imagery and metaphors are complex and not easily unravelled. Best, really, for each person to make of it what they will.

The walk occurred a little later in the concert and involved the audience following Susan Ellis (emulating the Pied Piper in voice) out of the Hall, across the lawn and into James Turrell’s “Skyspace”. Once there, we filed inside the cone in small groups and found three Griffyns sitting on the bench humming/chanting into the space. It was peaceful, harmonious – and reminded Mr Gums and me of some moving “art space” experiences in Japan, particularly from the Setouchi International Art Festival.

“Come walk with me”

The concert/show/performance (have you noticed that I don’t quite know what to call these events?) concluded on three pieces of music: “Umbilical Link” composed by Michael Sollis, with words by Alison Procter, “Landscape Escape”, and “Mountain Song”. “Umbilical Link” was inspired by Sollis’ walking around the suburb in which he grew up, and now lives in again. It’s about belonging, and it also connected to Boyd, to the fact that in the last two decades of his life he found a place he loved, Bundanon. In 1993 he gave Bundanon to the people of Australia because “you can’t own a landscape”.

Being Whispering Gums, I loved this line from “Umbilical Link”:

… big trees whispering moments from my histories.

“Landscape Escape”, a new song by the Cashews, referred specifically to Boyd’s finding Bundanon – “an intricate seduction on a canvas so vast”. The show then closed with an older Cashews’ work (I believe), “Mountain Song”, which neatly tied together the various themes that had been put to us – belonging, disconnection and discordance, respect for indigenous ownership, and a nurturing of the spirit. Australians will get the allusion in Lyons’ words, “the great divide is the great unification”. And with that, a few of the Griffyns picked up stones and sticks and playfully duelled with each other, percussively, before all took their well-deserved bows.

* For the second time this year, the programme was preceded by a support act, this time, appropriately, the local folk/folk-rock/hug pop group, Pocket Fox. We heard the last few songs and were impressed.

** I was trying to capture some lyrics as they were sung, so my quotations may not be exact.