Back in 2019, the Canberra Writers Festival sent subscribers a report on the event. I don’t think they’ve done so since, which is a shame, as I loved reading (and writing about) it. This year, thanks to Colin Steele, who runs the ANU/Meet-the-Author series, I was able to see a report on the Festival that was published in the paywalled Books+Publishing*.

The report included some stats:

- the festival recorded more than 10,000 audience attendees, an increase of 55% on the 2024 festival.

- the 5-day program included 114 events, of which 50 sold out and 24 reached 75% of audience capacity.

CWF also presented its inaugural schools program, and a Kids and YA day which featured writers like Andy Griffiths, Jack Heath, and Craig Silvey. These were apparently successful enough that they see opportunities “to further develop programs for younger audiences”. Excellent, eh?

Books+Publishing quoted CWF festival director Andra Putnis, as saying:

“The Canberra Writers Festival continues to grow because it connects people through story – whether they’re exploring global issues and politics or their love of literature, poetry, crime, memoir or page-turning fiction. This year’s record numbers show that Canberrans have an appetite for joyful and challenging conversations…

Gathering to listen to each other’s stories is what art and humanity are all about, and this year Canberra truly showed up for it. We really can’t thank enough all the international, interstate and local artists that came together to truly shine and share their work.”

I did not attend most of the big note sessions, such as those featuring Trent Dalton and Heather Rose. Time available, cost and the inevitable clashes all affect decision-making. And I really wanted to attend some of what sounded to be meatier sessions, like Reckoning, Our worlds, our way, and Poems of love and rage (see my posts linked below).

For me, it was an excellent Festival. When, in 2016, Canberra “got” a writers festival again, many of us fiction readers were frustrated that fiction did not feature highly in the program. Gradually, and particularly through Beejay Silcox’s time as Artistic Director, the balance shifted, resulting in far more sessions feeding those of us who aren’t only interested in history, memoir, and crime written by journalists (all of which are fine, I hasten to add! It’s the balance that was frustrating, not the individual works and their authors.) This year, this balance continued, and I felt spoilt for choice, which brings me to…

The main challenge of this Festival, for festival-goers anyhow. I have written about this before – and it is probably not an uncommon issue – but it’s the geographic spread of venues, across both sides of the lake. This is largely because the venues are sponsored, and who turns down a sponsor? The Festival does a good job of theming the different locations, which helps, but choices still have to be made. My practice is to choose a venue for a day on the basis of one or two events I really want to attend and then plan my bookings around that. Last year, that meant one day at one location, and the other day at another. This year it meant both days at the same location. For those who did some venue-hopping, it was, luckily, a good weekend weather-wise.

A few more facts

The National Library of Australia Bookshop, which was one of the participating booksellers, reported their Top Ten sales during the Festival. These sales presumably drew mostly from those sessions held at the Library so may not reflect the Top Ten sold throughout the Festival’s multiple venues, but we all like lists don’t we:

- Trent Dalton, Gravity let me go (Fourth Estate)

- Heather Rose, A great act of love (A&U)

- Garry Disher, Mischance Creek (Text, bought for Mr Gums for Christmas – don’t worry, he knows!)

- Brigid Delaney, The seeker and the sage (A&U)

- Hannah Kent, Always home, Always homesick (Picador)

- Madeleine Watts, Elegy, Southwest (Ultimo)

- Kathleen Folbigg and Tracy Chapman, Inside Out (Penguin)

- Devoney Looser, Wild for Austen (Ultimo, bought an e-version so mine won’t have counted here)

- Lev Grossman, The bright sword (Penguin)

- Rachael Johns, The lucky sisters (Penguin)

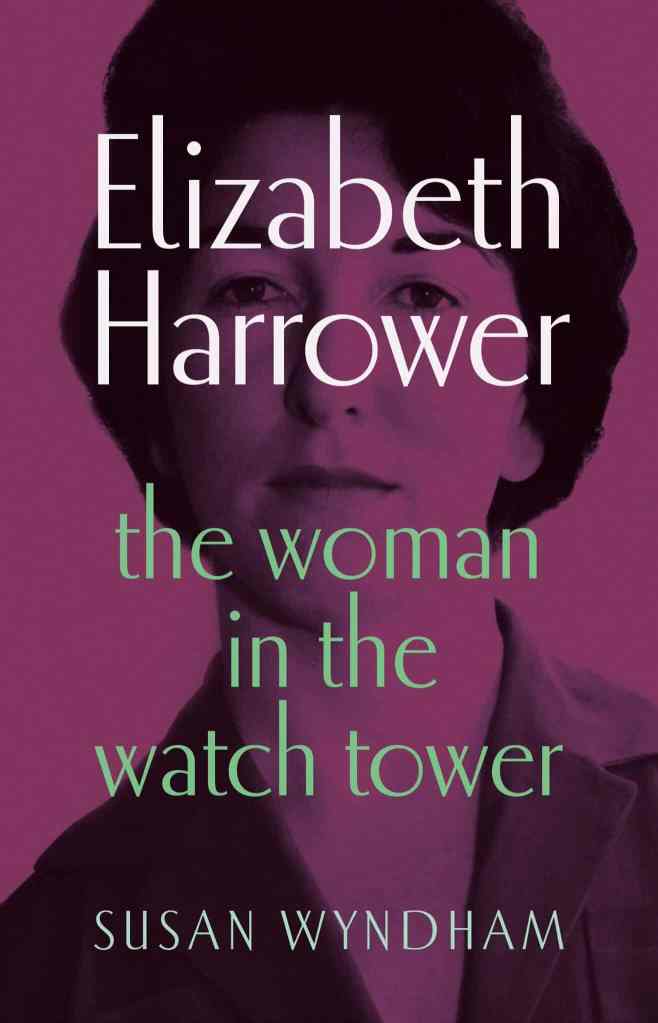

As you can see, I didn’t contribute much to this list, but I did buy some other books including Evelyn Araluen’s The rot, and some as gifts (so my lips are sealed). I already had some books relating to sessions I attended, including Darren Rix and Craig Cormick’s Wirra Wirra Wai and Susan Wyndham’s Elizabeth Harrower: The woman in the watchtower.

Back in 2019, I listed my posts in their order of popularity (that is, by number of hits), so I thought I’d do that again:

- All Things Austen: Jane Austen Anniversary Special (with Susannah Fullerton, Devoney Looser and Emily Maguire)

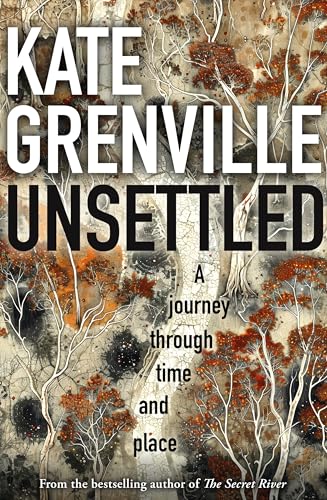

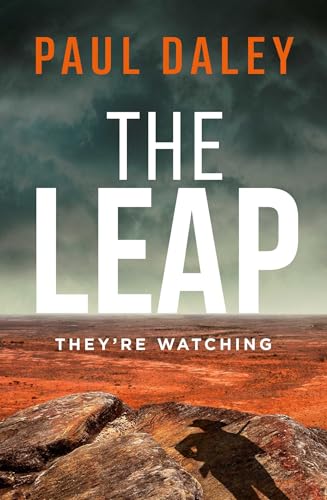

- Reckoning (with Craig Cormick, Paul Daley, Kate Grenville)

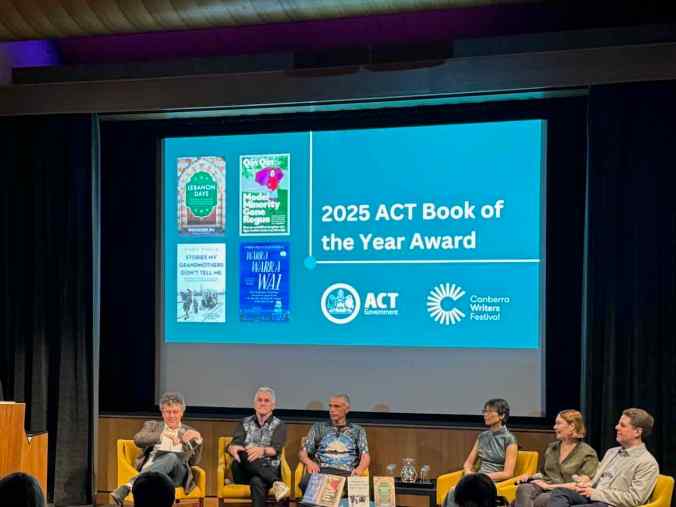

- (Tied) ACT Book of the Year (with Andra Putnis, Qin Qin, Darren Rix and Craig Cormick) AND Our Worlds, Our Way (with Evelyn Araluen, Lisa Fuller, and Jasmin McGaughey)

- Finding Elizabeth Harrower (with Susan Wyndham)

- Poems of Love and Rage (with Evelyn Araluen, Maxine Beneba Clarke and Omar Musa)

- What happened in the Outback (with Garry Disher and Gail Jones)

The posts ranked from 3rd to 6th were closely bunched, with the top and second ranked posts well out in front and somewhat separated from each other. You can tell something about my readers though, when you see that the crime-related session was my least popular post, while its participant Disher’s book (and Looser’s) were the only ones to make the Top Ten from the sessions I attended.

In conclusion …

Whatever the reason – programming, the weather, the truly engaged volunteers, and/or the fact that the cafe at my venue (the Library) stayed open for longer this year – there was a real buzz at this year’s festival. It was a joy to attend – and, I came away with some new insights and things to think about.

* This post draws partly from the Books+Publishing report (with the agreement of the Canberra Writers Festival).