In my recent post on Carmel Bird’s bibliomemoir, Telltale, I hinted that there could be another post in this book. There could, indeed, be many, but I must move on, and I must not spoil the book for others. However, given many blog-readers enjoy personal posts, I’ve decided to share a few of my particular delights in the book. I found myself frequently writing “Yes” in the margins …

“I’m glad, now, that I have always defaced books”

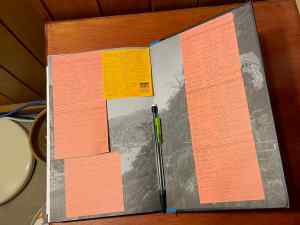

… because, like Carmel Bird, I have, since I was a student, “defaced” my books. Not only that, but my defacements seem to be of a similar ilk to hers. For example, I sometimes add an old envelope, or post-it notes, inside back covers to carry more notes. Like her, I love books with several empty pages at the back to accommodate note-taking.

Carmel Bird also loves indexes – and I love the fact that Telltale has a beautiful index, because such a book should, but often doesn’t. But, what really tickled me was her comment early in the book that “I also make a rough index on the empty pages at the ends of books I read” (or, as she also writes, “pencilled lists of key elements”). Yes! Sometimes, my indexes are more like notes, but other times my notes are more like indexes. Mostly, though, I do a bit of both, with exactly what depending on the book and on my response to it. This latter point is implied in Bird’s statement that:

In 2020, paying so much attention to books, I took particular notice of the differences in the ‘indexes’I had made at different times, how on each re-reading I had noticed different details.

Here, she not only shares her reading practice but also comments on reader behaviour, on the fact that each time we read a book we find something new. That can be for various reasons. On subsequent readings we already know the book at some level and so are ready to see more in it; on subsequent readings the world will have changed so the things we notice can also change according to the zeitgeist; and then, of course, the biggie, on subsequent readings, we ourselves have changed so we see the world differently. I love that Bird’s indexes reflect this – and that she saw it.

But, there’s a downside to all this “defacement”, which Bird also discusses. Writing about discarding books – the how and why – she says, “when I have annotated a book, it is not much use to anybody but myself, so selling it or giving it away are not possible solutions”. I know what she means, though I contest that hers would not be of use to anyone else. Who wouldn’t enjoy owning a book so defaced by her?

There is, however, a point at which she and I depart. When reading an outsize paperback becomes “too difficult … to manage comfortably” she will attack it “vertically down the spine with an electric carving knife” to divide it into manageable portions. I know some travellers tear out sections of travel guides they no longer need, but librarian-me finds destruction a step too far. Sorry Carmel, I understand, but …

“oh what a lovely word”

Like many authors, Carmel Bird loves words. It’s on show in all her work, but in Telltale, it’s front and centre. In her opening chapter, she writes that

Uncle Remus uses terms such as ‘lippity-clippity’. This is the kind of singing, onomatopoeic language I sometimes invent when writing.

And, so she does, even in this nonfiction bibliomemoir. Did it come from reading Uncle Remus “all that time ago”, she ponders. Was it “embedded” in her brain, back then, without her “even realising”? Probably.

Throughout Telltale, Bird discusses words – how they have changed over time (in meaning, for example, or in acceptability), how they look, where they come from, how they sound. As the daughter of a lexicographer, I would be interested in this. As a lover of Jane Austen whose wit and irony I adore, I would be interested in this. And, as one who loves writing that plays well in the mouth and sounds great to the ear, I would be interested in this. If you love words too, this book will be an absolute delight for you.

Other delights

As I said when opening this post, I really mustn’t spoil this book for others, so I’ll just add a few other delights:

- her discussions of the many books and stories she chooses to share – those she found on her shelves that she felt illuminated her life and writing. I’ve mentioned very few of these because, really, this is the thing that most readers will want to discover and enjoy. Get to it … Meanwhile, I will name just two here. One is Dickens’ Bleak House which she writes “might” be her favourite Dickens. It might be mine too. The other is Marjorie Barnard’s “The persimmon tree” which she describes as “extraordinarily powerful”. Barnard’s “The persimmon tree and other stories” is one of the only short story collections I’ve read more than once. I concur!

- silly little things like the fact that she loves green (as do I) and that she learnt that “lovely” word “tessellated” at the tessellated pavement at Tasmania’s Eaglehawk Neck (as did I).

- she loves the internet and allowed herself to use it for this book. She was the first fiction writer in Australia to have a website. Like most of us, she prefers printed books, but she also sees the advantage of electronic books (including the ease of searching them – as an index-lover would!)

Finally, early in the book, Bird discusses memory:

As is often the case with memory, while some of physical details are clear, the principal element that has been retained is the feeling. Perhaps the feeling is the meaning.

Yes! This makes sense to me. I can rarely remember plots or denouements, but for the books that are special to me, I can remember how they made me feel – uplifted, melancholic, inspired, distressed, excited, angry, and so on. These feelings are surely associated with what the author intended us to take away, and therefore they must reflect the meaning?

Here, I will, reluctantly, leave Telltale, but I’ll do so on one of its three epigraphs, the one from her own character:

‘memory

is the carpet-bag

mire of quag

filled with light-dark truth-lies

image innation

and butterflies’CARILLO MEAN,

Remembrance of Wings Past

How can you not love this?