Although it is quite a traditional memoir, style-wise, Jocelyn Moorhouse’s Unconditional love: A memoir of filmmaking and motherhood is particularly interesting for a couple of reasons. Firstly, she’s an artist who had a happy childhood. Who knew that could happen? Secondly, while most memoirs focus on one aspect of the writer’s life – such as their career (sport, for example), their trauma (childhood abuse, perhaps), their activity (like travel) – Moorhouse intertwines two ostensibly distinct parts of her life, her filmmaking career and her life as a mother.

Although it is quite a traditional memoir, style-wise, Jocelyn Moorhouse’s Unconditional love: A memoir of filmmaking and motherhood is particularly interesting for a couple of reasons. Firstly, she’s an artist who had a happy childhood. Who knew that could happen? Secondly, while most memoirs focus on one aspect of the writer’s life – such as their career (sport, for example), their trauma (childhood abuse, perhaps), their activity (like travel) – Moorhouse intertwines two ostensibly distinct parts of her life, her filmmaking career and her life as a mother.

Jocelyn Moorhouse will be known to many filmgoers as the director of the critically successful Proof, How to make an American quilt, and The dressmaker. She is also the wife of PJ Hogan who directed Muriel’s wedding, My best friend’s wedding, and Peter Pan. This is one amazing couple. Not only have they each made critically successful films, but they are lifetime creative and life partners, working on and/or supporting each other’s movies, negotiating the logistics of parenthood, and so on. They have made it work for over 30 years, in a way that few do. That’s impressive.

It could all, then, have been pretty idyllic, but life rarely turns out that way, and for Moorhouse and Hogan it didn’t. The reason is that of Moorhouse and Hogan’s four children, the middle two are autistic. This resulted in an 18-year hiatus in her filmmaking career, although during that time she kept her hand in, mostly working in some way with PJ on his projects. The book, then, tells both stories, the development of her career from her early studies in media and drama at Rusden State College and then at the Australian Film and Television School, where she met Hogan, and her very particular and demanding life as the mother of two autistic children.

She shares the emotions of giving birth to two gorgeous children only to have them regress around two years of age, as is apparently typical with autism, into unhappy, and therefore difficult children. I say unhappy because it is clear that the children suddenly find the world confusing and frustrating. Their language and communication skills regress so they resort to screaming and crying, and other difficult behaviours. Moorhouse talks about the shock of diagnosis, the therapies they try, including the ones that work (for them), and the logistics of running a family whose life is peripatetic and dependent on the next film job coming along.

Moorhouse, the experienced storyteller (and in fact problem-solver), tells her story carefully. It’s not until halfway through the novel that she brings us to her growing uneasiness about her second daughter, Lily, and Lily’s diagnosis. It’s a tough chapter, because it was a shock to her. She realises that her discussion of causes, not to mention possible preventions and cures, could upset some readers:

I am aware that some of the readers of this book may be autistic themselves and could possibly find this chapter upsetting. Please understand that I wasn’t rejecting Lily because of her autism. If you keep reading, you will discover that I love her autism and her brother’s too. But twenty years ago I was afraid for Lily’s future …

It is tricky to write about issues like this, without offending unintentionally. It’s a long “journey”, to use current terminology, that she and her family go on. And it’s a hard one. Late in the book she says that it took her years to realise that a lot of the pain she was feeling stemmed from “an internal war between my instinct to cling to the dreams about life, and my need to accept the truth”. By the end, she and PJ learn to rebuild their dreams for Lily and Jack, and she learns to balance her need to work against the family’s needs.

This brings me to her career. I enjoyed reading about that, about her own films and the insight she gave me into a film director’s work in general. I worked with film – from an archival point of view – and met various film industry people over the years, but I still learnt much about just what a director does from this book, such as the amount of script work they (might) do, the work involved in casting, choosing location and designing sets, and so on. Each director has his/her own way of doing things, it’s clear, but I greatly enjoyed reading about Moorhouse’s experiences – the wins and losses, the need to be philosophical about those that got away or didn’t go to plan.

Style-wise, Unconditional love is a straightforward chronological memoir, told in plain language, making it an accessible read. A lovely, though not unusual thing she does, is to begin each chapter with a quote. They come from diverse sources, including filmmakers (like Ingmar Ingmar Bergman and Frederico Fellini), writers (like Virginia Woolf and Maya Angelou), people who treat or have autism (like Oliver Sacks and Temple Grandin), and artists (like Marc Chagall). The opening quote, for the introduction, comes from Margaret Atwood, saying that, “in the end, we’ll all become stories”, which seems perfect for both a memoir and a filmmaker.

This is a generous memoir, rather than a tell-all one. There’s little name-dropping, though of course names are dropped because that’s the business she and Hogan are in. There are references to relationship and financial challenges – you’d be surprised if there weren’t any – but these aren’t dwelt upon. She also seems careful to not intrude unnecessarily on her children’s rights to their own lives, particularly as they get older.

Unconditional love is a book that will appeal to readers interested in Australian filmmakers, to those interested in families with autistic members, but most to anyone interested in a story that shares the challenges of a life but focuses more on the solutions.

Jocelyn Moorhouse

Jocelyn Moorhouse

Unconditional love: A memoir of filmmaking and motherhood

Melbourne: Text Publishing, 2019

296pp.

ISBN: 9781925773484

(Review copy courtesy Text Publishing)

Karen Viggers: Is passionate about Tasmania, wilderness, freedom, empowerment, forests, and friendship. Her novel is about three outsiders in a small timber town, and explores how people create bonds and belonging in such places.

Karen Viggers: Is passionate about Tasmania, wilderness, freedom, empowerment, forests, and friendship. Her novel is about three outsiders in a small timber town, and explores how people create bonds and belonging in such places. Nigel Featherstone: Wanted “to piss off Tony Abbott”. Seriously though (or, also seriously), the book resulted from a “strange decision” to apply for an ADFA (Australian Defence Force Academy) residency in 2013, despite having no interest in war. Of course, the residency did come with $10K! Featherstone’s overriding interest was to explore different expressions of masculinity under military pressure. Eventually, he found two books in the ADFA Library: Deserter, by American Charles Glass, which explored desertion as an act of courage, and Bad characters, by Australian Peter Stanley, which included the story of a soldier who, during World War 1, had been caught in a homosexual act, been found guilty, and never turned up to board the ship to take him home to prison! There’s my novel, he decided. Had he had any reaction from ADFA to the book, Alberici asked. No.

Nigel Featherstone: Wanted “to piss off Tony Abbott”. Seriously though (or, also seriously), the book resulted from a “strange decision” to apply for an ADFA (Australian Defence Force Academy) residency in 2013, despite having no interest in war. Of course, the residency did come with $10K! Featherstone’s overriding interest was to explore different expressions of masculinity under military pressure. Eventually, he found two books in the ADFA Library: Deserter, by American Charles Glass, which explored desertion as an act of courage, and Bad characters, by Australian Peter Stanley, which included the story of a soldier who, during World War 1, had been caught in a homosexual act, been found guilty, and never turned up to board the ship to take him home to prison! There’s my novel, he decided. Had he had any reaction from ADFA to the book, Alberici asked. No. Kathryn Hind: Believes her senses were heightened because she started writing in England, when she was missing Australia. She couldn’t do physical research so would “drop a pin on map”. She named real places. She didn’t feel she had to capture exact their reality, but the timings of Amelia’s journey had to be right. I love that she used online traveller reviews to inform herself. For example, a review of a hotel in a little town mentioned being kept awake by trains shaking the walls at night. She used that! She wanted to truly test Amelia to bring out her strength.

Kathryn Hind: Believes her senses were heightened because she started writing in England, when she was missing Australia. She couldn’t do physical research so would “drop a pin on map”. She named real places. She didn’t feel she had to capture exact their reality, but the timings of Amelia’s journey had to be right. I love that she used online traveller reviews to inform herself. For example, a review of a hotel in a little town mentioned being kept awake by trains shaking the walls at night. She used that! She wanted to truly test Amelia to bring out her strength. Then it was Patrick Mullins. He was tricky in terms of “place”, so Alberici asked him about the title. Mullins admitted that his publisher chose it – using Gough Whitlam’s description of McMahon’s scheming by telephone. Mullins’ own title is the subtitle. Alberici asked if he had any cooperation from the family. None, said Mullins, though he sent messages and did have coffee with one member. So, he couldn’t access the 70 boxes of McMahon’s papers at the Archives. He understood, he said. Children of politicians have crappy lives, and, anyhow, it freed him from feeling beholden to the family. Silly family, eh? Fortunately, he had access to one of McMahon’s autobiography ghostwriters who had seen the papers. The most startling revelation, he said, responding to another question from Alberici, was that McMahon was “more admirable than we would have thought”. He racked up several significant achievements, including taking us to the OECD, and showed impressive persistence/resilience.

Then it was Patrick Mullins. He was tricky in terms of “place”, so Alberici asked him about the title. Mullins admitted that his publisher chose it – using Gough Whitlam’s description of McMahon’s scheming by telephone. Mullins’ own title is the subtitle. Alberici asked if he had any cooperation from the family. None, said Mullins, though he sent messages and did have coffee with one member. So, he couldn’t access the 70 boxes of McMahon’s papers at the Archives. He understood, he said. Children of politicians have crappy lives, and, anyhow, it freed him from feeling beholden to the family. Silly family, eh? Fortunately, he had access to one of McMahon’s autobiography ghostwriters who had seen the papers. The most startling revelation, he said, responding to another question from Alberici, was that McMahon was “more admirable than we would have thought”. He racked up several significant achievements, including taking us to the OECD, and showed impressive persistence/resilience. PM’s Pick, featuring the multi-award-winning Brian Castro, was another must-attend session. The night before, while dining at Muse, I checked to see whether they had any Castro in their classy little bookshop. They did, including a second-hand copy of his fourth novel, After China. I snapped it up, and as I did, bookseller Dan reminded me that he’s “very literary”. I know, I said! He is also very reclusive, making this a not-to-be missed session. And it was free, my original payment being refunded when they found a sponsor. Woo hoo!

PM’s Pick, featuring the multi-award-winning Brian Castro, was another must-attend session. The night before, while dining at Muse, I checked to see whether they had any Castro in their classy little bookshop. They did, including a second-hand copy of his fourth novel, After China. I snapped it up, and as I did, bookseller Dan reminded me that he’s “very literary”. I know, I said! He is also very reclusive, making this a not-to-be missed session. And it was free, my original payment being refunded when they found a sponsor. Woo hoo! Castro conversed with local ABC radio presenter Genevieve Jacobs. It was a smallish audience, and a quiet conversation, but provided some fascinating insights.

Castro conversed with local ABC radio presenter Genevieve Jacobs. It was a smallish audience, and a quiet conversation, but provided some fascinating insights. Now, I should say a little about Blindness and rage. Inspired by Virgil, Dante (the 34 cantos of his Inferno), and Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin, it tells the story of writer Lucien Gracq who, told he is terminally ill, goes to Paris to finish the epic poem he’s writing and to die there. He joins a secret writers’ society, Le club des fugitifs, which only dying writers can join. It publishes an author’s last unfinished work, but not in his/her name. This reflects Castro’s own view that the work is all, the writer doesn’t matter! He doesn’t think fame helps anything.

Now, I should say a little about Blindness and rage. Inspired by Virgil, Dante (the 34 cantos of his Inferno), and Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin, it tells the story of writer Lucien Gracq who, told he is terminally ill, goes to Paris to finish the epic poem he’s writing and to die there. He joins a secret writers’ society, Le club des fugitifs, which only dying writers can join. It publishes an author’s last unfinished work, but not in his/her name. This reflects Castro’s own view that the work is all, the writer doesn’t matter! He doesn’t think fame helps anything. Today was the day I was able to devote to fiction writers. There were still clashes, but there was never any doubt that I would attend this Tara June Winch session, even though it meant missing a panel featuring Charlotte Wood, Brian Castro, and Simon Winchester. Why were these scheduled opposite each other?! The Festival-goers complaint! Anyhow, fortunately, as you’ll see, I did get to hear Brian Castro too; and I have seen Charlotte Wood before and did see Simon Winchester in

Today was the day I was able to devote to fiction writers. There were still clashes, but there was never any doubt that I would attend this Tara June Winch session, even though it meant missing a panel featuring Charlotte Wood, Brian Castro, and Simon Winchester. Why were these scheduled opposite each other?! The Festival-goers complaint! Anyhow, fortunately, as you’ll see, I did get to hear Brian Castro too; and I have seen Charlotte Wood before and did see Simon Winchester in  Winch explained The yield’s genesis. Ten years in the writing, it was inspired by a short course she did in Wiradjuri language run by Uncle Stan Grant Sr (father of Stan Grant whom I’ve

Winch explained The yield’s genesis. Ten years in the writing, it was inspired by a short course she did in Wiradjuri language run by Uncle Stan Grant Sr (father of Stan Grant whom I’ve  It’s a curious thing, isn’t it? When I write my book reviews, I spend very little time on the content, focusing mostly on themes, style and context, but when I write up festivals and other literary events I find it hard to be succinct about the content. Perhaps this is because I can always go back to the book to check something, while these events are fleeting. Once they’re gone, they’re gone, so I want to capture all I can. Of course, many events these days end up as podcasts, but you can’t be sure how long they’ll be there. Anyhow, that’s my excuse and I’m sticking to it …

It’s a curious thing, isn’t it? When I write my book reviews, I spend very little time on the content, focusing mostly on themes, style and context, but when I write up festivals and other literary events I find it hard to be succinct about the content. Perhaps this is because I can always go back to the book to check something, while these events are fleeting. Once they’re gone, they’re gone, so I want to capture all I can. Of course, many events these days end up as podcasts, but you can’t be sure how long they’ll be there. Anyhow, that’s my excuse and I’m sticking to it … Pomeranz began, it seemed to me, by wanting to focus more generally on book-to-film adaptations, but Beresford focused, not surprisingly I suppose given the session topic, on The women in black/Ladies in black.

Pomeranz began, it seemed to me, by wanting to focus more generally on book-to-film adaptations, but Beresford focused, not surprisingly I suppose given the session topic, on The women in black/Ladies in black. And then it was time to hop into the car, and drive over the lake for the sold-out session (as indeed was my first session of the day), Simon Winchester in conversation with Richard Fidler. There was no time for lunch!

And then it was time to hop into the car, and drive over the lake for the sold-out session (as indeed was my first session of the day), Simon Winchester in conversation with Richard Fidler. There was no time for lunch! First though – oh oh, will I still be able to keep this short – the book is cleverly (though probably still chronologically) structured according to increasing levels of precision (or, to put it another way, decreasing levels of tolerance.) So, Chapter 1 is Tolerance 0.1, Chapter 2 is 0.0001, right up to Chapter 9, the second last chapter, which is a mind-boggling: 0.000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 01! We are talking precision after all!

First though – oh oh, will I still be able to keep this short – the book is cleverly (though probably still chronologically) structured according to increasing levels of precision (or, to put it another way, decreasing levels of tolerance.) So, Chapter 1 is Tolerance 0.1, Chapter 2 is 0.0001, right up to Chapter 9, the second last chapter, which is a mind-boggling: 0.000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 01! We are talking precision after all! This session was recorded for ABC RN’s Big Ideas program, and the host of that show, Paul Barclay, moderated the panel. The panel members were

This session was recorded for ABC RN’s Big Ideas program, and the host of that show, Paul Barclay, moderated the panel. The panel members were The session was billed as follows: “Some of Canberra’s finest and most creative writers join forces in this irresistible ode to the national capital. Take a wild ride through a place as described by the vivid imaginations of some of this city’s best talents. Capital Culture brings stories not just of politics and power, but of ghosts and murder and mayhem, of humour and irreverence, and the rich underlying lode that makes Canberra such a fascinating city.”

The session was billed as follows: “Some of Canberra’s finest and most creative writers join forces in this irresistible ode to the national capital. Take a wild ride through a place as described by the vivid imaginations of some of this city’s best talents. Capital Culture brings stories not just of politics and power, but of ghosts and murder and mayhem, of humour and irreverence, and the rich underlying lode that makes Canberra such a fascinating city.”

Sarah Krasnostein’s The trauma cleaner: One woman’s extraordinary life in death, decay & disaster (Biography) (

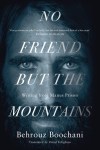

Sarah Krasnostein’s The trauma cleaner: One woman’s extraordinary life in death, decay & disaster (Biography) ( The overall winner, announced last Monday, 12 August, is Behrouz Boochani’s No friend but the mountains.

The overall winner, announced last Monday, 12 August, is Behrouz Boochani’s No friend but the mountains.