For my third post in my Monday Musings 1923 series, I’m moving away from publisher initiatives, like the NSW Bookstall Co and the Platypus Series, to something a bit different. It’s an intriguing story about what one paper called “inter-Imperial amity”. It goes like this …

Mr. George H. Locke (1870-1937) – as the newspapers of the day referred to him – was, at the time, the Chief Librarian of the Public Library of Toronto. He was significant enough to have a Wikipedia page, which tells us that he had that role from 1908 to his death. Wikipedia also says that he was the second Canadian to be president of the American Library Association (ALA). The Toronto Public Library website tells us a little more. He was their second chief librarian, and his memorial plaque credits him with having “transformed a small institution into one of the most respected library systems on the continent.” They say he was the first Canadian to be president of the ALA – but who’s counting! The important point is that he was an active librarian who not only “promoted library training and professionalism” but was intellectually engaged in the world of letters.

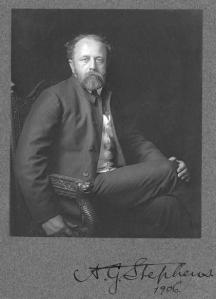

All very well, I hear you saying, but what’s that got to do with us? Well, in 1923, he commissioned Mr. A.G. Stephens (1865-1933) to “choose the best 100 imaginative Australian and New Zealand books for exhibition in the Toronto library” (as reported by many newspapers of the day, like Brisbane’s The Queenslander, 3 March 1923). His aim, the newspapers say, was “to inform Canadian readers of the literary aspirations and performances of Australian and New Zealand authors”. This is an inspired and inspiring librarian!

Now, A.G. Stephens, who also has a Wikipedia page, is well known to those steeped in the history of Australian literary criticism and publishing. He was famous for his “Red Page” literary column in The Bulletin, which he ran for over a decade until 1906. Stuart Lee, who wrote Stephens’ ADB article, says of this column:

Stephens’ common practice was to spark controversy by attacking an established writer, such as Burns, Thackeray, Kipling, or Tennyson, thereby enticing correspondents as varied as Chris Brennan or George Burns to attack and counter-attack, sometimes over weeks. It was heady stuff.

After leaving The Bulletin, Stephens worked as a freelance writer and editor. Some of the newspaper articles reporting on Mr. Locke’s initiative, also reference Stephens’ being the editor of the literary magazine, The Bookfellow. He had edited 5 issues of it in 1899, and then revived it as a weekly for a few months in 1907. After that more issues were published, at intervals, until 1925. Overall, Stephens was recognised for his criticism, literary journalism and literary biography. After he died, critic Nettie Palmer, writes Stuart Lee, complained about ‘the appalling lack of public response’ to the news of his death, while Mary Gilmore wrote in an obituary, that “only those who were intellectually shaped by his hand, only those who stood on the strong steps of his work, know with what a sense of loss the words were uttered, ‘A. G. Stephens is gone’.” All this suggests that he was a person well-placed to fulfil Locke’s commission.

So, back to the commission. I found very little detail about it. Most of the papers announcing it merely explained what it was – which is what I’ve told you already. A few made the point – as did The Queenslander above – that ‘The “hundred best books” task has not been attempted in Australia before. An initial difficulty is that many of our best books are out of print, and have to be painstakingly sought for.’

But, here’s the thing, on 3 August 1923, a few months after the commission was announced, The Sydney Morning Herald reminded readers of the commission, and then wrote

The collection has now been made, and the books have been despatched to Canada.

Nothing more! Back to the drawing board for me. After trying various search strategies – which produced a few comments on the list – I finally found the full annotated list. It’s way too long to share in this post – and it needs a lot of editing in Trove for it to be shareable. In the meantime, I’ll whet your appetite with this response to the list by critic and poet Louis Esson (1878-1943) in Melbourne’s The Herald (1 September 1923):

Mr Stephens has now published his list of a hundred representative books. As might have been expected, they make a rather arbitrary and unsatisfactory collection. Half of them at least might have been omitted with advantage. Mr Stephens has an exaggerated opinion of the value of the writings and critical opinions of Mr A. G. Stephens. Fifteen of his hundred representative books have been either written or edited by himself. A number of feeble writers have been included while more important writers like Bernard O’Dowd, Frank Wilmot, Vance Palmer, Francis Adams, Walter Murdoch, Katharine Susannah Prichard, Price Warung and others are inadequately represented or not selected at all. Mr Stephens, no doubt, has done his best. He has a perfect right to his own opinion; but readers in Canada and Australia must be on their guard against accepting A.G.S.’s list as being in any way critical or authoritative.

Esson isn’t the only one who commented on Stephens including himself.

If you are interested, watch this space … the list is not quite what I expected, based on those early announcements. I’ll try to share it next week.

Picture Credit: Alfred Stephens, 1906, Public Domain, from National Library of Australia.

Other posts in the series: 1. Bookstall Co (update); 2. Platypus Series