Yesterday, as I was trying to untangle a curly identification for my next Australian Women Writers blog post, I came across an interesting article in The Brisbane Courier. Published on 15 October 1927, and penned by one W.M., the 1300-word article is titled “Queensland Women Writers: Poets and Novelists“. Of course, it caught my attention, and not only because buried within was an important clue for my puzzle (about which I might write next Monday).

Although I’ve written several Trove-inspired posts about Australian literature in the 1920s and 30s, this one caught my attention for two reasons – it is focused on just one state (Queensland) and is limited to women writers. I don’t know whether W.M. wrote separately about Queensland’s men writers, because it’s hard to search on by-lines like “W.M.” I did try to identify him. He may be William Marquis Kyle, whom I came across via an announcement for a lecture to be given by “Mr. W.M. Kyle, M.A.” He was appointed Professor of Philosophy at the University of Queensland in 1938. The best record I found for him included that “he gave public lectures, wrote and reviewed newspaper articles and was well known as a broadcaster”. So, on this slim basis, I am going to refer to “W.M.” as he/him.

Queensland women writers

W.M. commences by talking about poetry, arguing that

When we contemplate the work of Australian writers, we can hardly fail to be impressed with the large proportion who have chosen poetry rather than prose as their medium. May it not be that a young nation, like a young writer, turns to poetry as more fitting than prose to express wonder and joy in a country which inspires emotions and sensations most appropriately uttered in lyrical form?

He goes on to say that whether his reasoning is true or not, “there is a larger amount of creditable verse than prose in the imaginative literature of Australia” and this is “apparent in any survey of the women writers of Queensland and their work”. But, he says, two novelists do occupy the first and last positions in his chronological list of Queensland women writers: Mrs Campbell Praed and Mrs Dorothy Cottrell. Both have appeared on my blog before.

W.M.’s article starts with brief paragraphs on the older writers. They are (links go to their Wikipedia pages):

- Mrs Campbell Praed (or, Rosa Campbell Praed)

- Mrs M.H. Foott (or, Mary Hannay Foott)

- Mrs M. Forrest (or, Mabel Forrest)

- Mrs Coungeau (or, Emily Coungeau)

- Sumner Locke (the mother of the better-known Sumner Locke Elliot)

- Mrs Emily Bulcock (who is commemorated in Canberra, through the street name, Emily Bulcock Crescent)

For these six writers, W.M. identifies a work or two, and adds some assessment or description. I’m not sure why he allows Sumner Locke her own name, given she married Henry Logan Elliott. Perhaps it’s that most if not all her works were published before she married, and she died the following year. Anyhow, he praises her, saying “her style was forcible and direct, as shown in her novels”.

He has positive words for all these writers. Of Rosa Praed, he says:

Her style was simple and illustrative, and she had the faculty of making her characters “live.” Her descriptions of the social life of early Brisbane, centring in Government House, show that in many respects the social life of the present time still resembles that of 30 years ago.

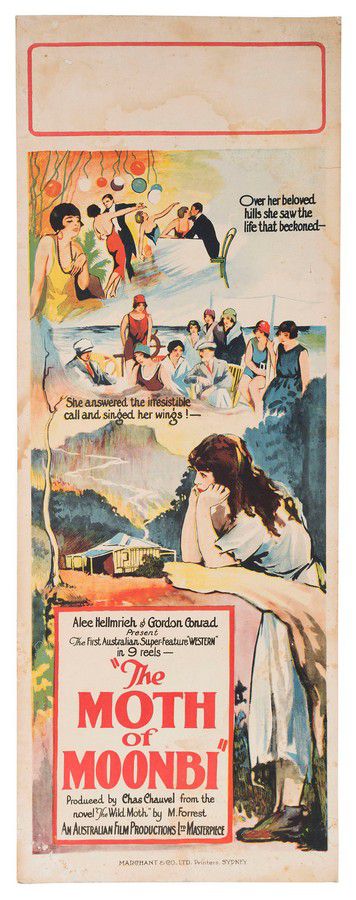

Mary Hannay Foott’s “poetic style was simple, but distinguished by considerable lyrical power”, and he praises her versatility. Mabel Forrest’s early promise, evident in a story published when she was 10, “has been fulfilled by an exceptionally large output of poetry, short stories, descriptive articles, and novels”. And, while her novels “contain many descriptive passages of outstanding charm and sincerity, upon her verse rests her claim to rank among the foremost writers of Australia to-day.” Her novel The wild moth was adapted to screen by Charles Chauvel in The moth of Moonbi.

Emily Coungeau had, he says, “a mind attuned to the beauty of Nature and the best in human hearts” which enabled her “to produce verse of much charm and sensibility”. Emily Bulcock’s poetry, on the other hand, was characterised by a “strong spiritual note”.

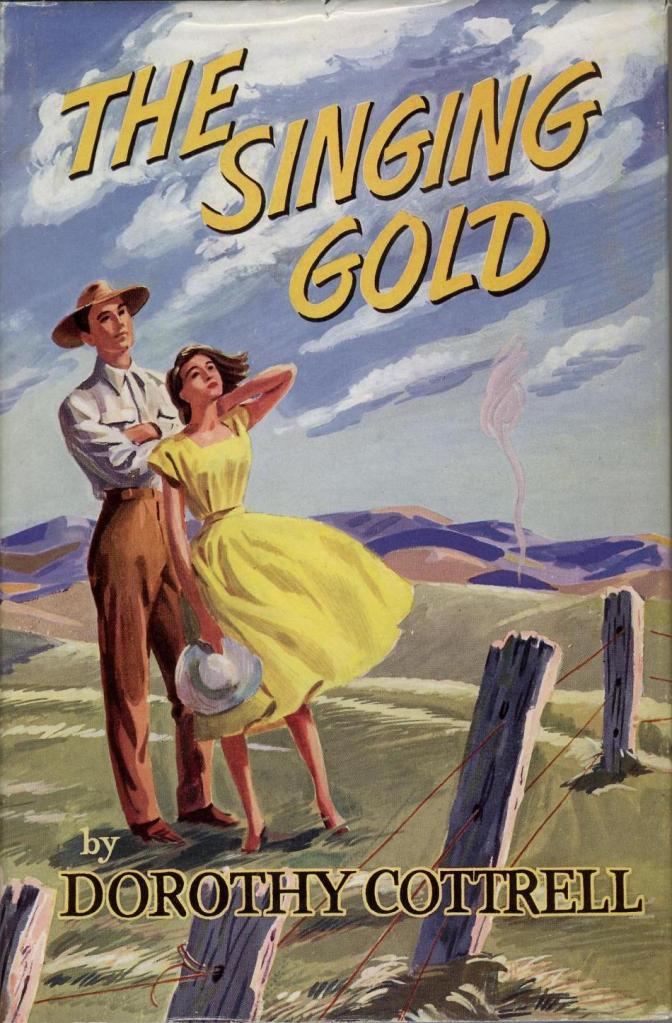

The rest of the writers, listed under the heading “Other writers”, are given one sentence or less, with the exception of the first in the list, Zora Cross. Her reputation has lasted more than most of the above. The reason for the short shrift given to her seems to be that she made her home in Sydney, so, not really a Queensland writer it seems! Few of the others are remembered today, except perhaps for the last on his list, the aforementioned Mrs Dorothy Cottrell. She, he writes, “is hailed by American publishers as a writer of exceptional power”. Her novel The singing gold was first serialised in The ladies home journal. The cover here is the 1956 edition (obvious from the fashion!) which suggests she remained popular for some time. A later story of hers became Ken Hall’s 1936 film, Orphan of the wilderness.

However, I will comment on one other. Wikipedia and the ADB have an entry for Nelle Tritton (1899-1946) whom Wikipedia writes as Lydia “Nellé” Tritton, and ADB as Lydia Ellen (Nell) Tritton. She had an interesting life. She was born in Brisbane in 1899, but in her mid-20s, she went to London and toured Europe, gained “a reputation for knowledge of international affairs”, and married a former officer of Russia’s White Army. The marriage ended in 1936, and in 1939, she married the exiled Russian prime minister Alexander Kerensky in Pennsylvania. ADB writes of their time in America that “their life, when they were together, was idyllic, with numerous visitors and games of croquet”. W.M. tells us none of this – much of which happened after 1927 – but it’s interesting that he’s included her, given she was barely in Australia. All he says of her is that “while still in her teens” she wrote a booklet of “Poems”. Curious – but fascinating.

W.M. concludes that, from his brief survey, “it is evident that the work of Queensland writers has reached a standard which justifies and claims adequate attention from the reading public”, and he quotes literary critic Bertram Stevens, who had died in 1922 but had apparently said:

Australia has now come of age, and is becoming conscious of its strength and its possibilities. Its writers to-day are, as a rule, self-reliant and hopeful. They have faith in their own country; they write of it as they see it, and of their work and their joys and fears in simple direct language.