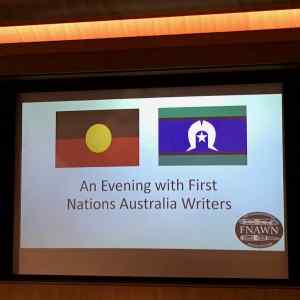

My first day of the Canberra Writers Festival ended with a bang – two hours with several of Australia’s top indigenous writers, organised by FNAWN (First Nations Australia Writers Network). It was a not-to-be-missed event, and was divided into two parts:

My first day of the Canberra Writers Festival ended with a bang – two hours with several of Australia’s top indigenous writers, organised by FNAWN (First Nations Australia Writers Network). It was a not-to-be-missed event, and was divided into two parts:

- “Because of her I can”: poetry readings with Ellen van Neerven, Yvette Holt, Jeanine Leane and Charmaine Papertalk Green

- Sovereign People – Sovereign Stories: a panel discussion with Kim Scott, Melissa Lucashenko, Alexis Wright, and moderated by Cathy Craigie

I liked this structure: the poets provided a emotive introduction to panel’s intellectually-focused discussion (not that the poems weren’t underpinned by intellect, mind you.)

“Because of her I can”

I’m just going to list the poets and their poems, as well as I can, as I did for the Canberra poets session earlier in the day. You may like to research them, though I’ve provided some links …

Jeanine Leane

Leane, whose unforgettable novel Purple threads I’ve reviewed here, started off – after acknowledging “the land never ceded” – with four poems:

- “Lady Mungo speaks“: first person poem about the egregious removal in a suitcase of Lady Mungo’s bones: “They spread me out like a jigsaw –/each piece an important part of their/puzzle of landscape and history.” Their puzzle!

- “Evening of the day”

- “River memory”: clever poem inspired by Gundagai’s Prince Alfred Bridge representing the idea of Australia’s “longest bridge, shortest history”, and subverting that to an indigenous perspective of “short bridge and long history”

- “Canberra 100 years on”

Yvette Holt

Holt, a David Unaipon Award winning poet and academic, also read four poems:

- “Progenitor”, an unpublished poem for her mother

- “Through my eyes” (from Anonymous premonition), suits this year’s NAIDOC theme

- ‘My mother’s tongue”, an unpublished poem about her mother who has dementia, exploring the issue of passing language between generations. I loved the line, “mother begins to scribble in her tongue in a language I do not understand”

- “Motherhood”, a poem dedicated to her daughter Cheyenne Holt, when she was 7

Ellen Van Neerven

Van Neerven is a younger writer who has appeared several times in my blog. She dedicated her poems to black women in her life whom “she loves”:

- “Orange crush”, for her mother: a found poem using lines from an inflight mag. (That got a laugh.)

- “Bold and beautiful”, for her nanna: a humorous poem playing on her nanna’s love of the soap opera

- “Home”, for her girlfriend Tia: a gorgeous love poem

- “Queens”, for “the black women here tonight”

Charmaine Papertalk Green

New-writer-for-me Green hails from Western Australia. She read published and unpublished poems to honour women in her family:

- “To the women of the land understand”: encouraging women to “remember your ancestors, remember your elders”

- “My mother belonged to me”: included lines in language.

- “Mothers letters”: I love writing letters, so loved this poem about her mother’s letters and the idea of “papertalking” but also that it’s “not just letters on paper”

- “Grandmothers”: about mining ruining country

- “Honey lips to bottlebrush”: about intergenerational cultural teaching.

You can hear her on ABC’s The Hub.

Jeanine Leane then returned to the podium, with the other poets, to pay tribute to Kerry Reed-Gilbert for her work with FNAWN, the Us Mob Writing Group, and in organising the Workshop coinciding with this Festival. She then read Oodgeroo Noonuccal’s poem “Song of hope.”

Sovereign People – Sovereign Stories

How lucky we were to have the above highly-respected poets, followed by, as moderator Cathy Craigie said, “three of Australia’s most dynamic writers”, Melissa Lucashenko, Kim Scott, and Alexis Wright (on the screen). The auditorium, which seats 300, must have been around three-quarters full, comprising indigenous and non-indigenous people from a range of ages. I hope they were pleased with the turnout. It certainly felt good to be part of it, which brings me to an important issue that came up in the Q&A and was also on my lips. It concerns what “white allies” can do. We can, of course, attend and support events like this, we can listen and learn from these events, and we can read the authors. It’s a challenge, though, I find to do this with the right tone – to not sound condescending, for example, when we try to “help” or empathise; to not assume we know or understand things we really don’t; to know how to communicate what we do know. It’s a fraught (though I recognise privileged) space to be in … but the important thing is to keep trying, isn’t it?

Anyhow, Cathy Craigie introduced the session, explaining that its focus was FNAWN’s theme for the week, intellectual sovereignty. She reminded us of the long history of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander writing in Australia – dating back to Bennelong’s letter to the Governor, and Maria Lock in the 1820s – and talked about the négritude movement in 1930s France, which promoted pride in racial identity.

The discussion then to-and-fro’d, with Craigie injecting questions regularly. I loved, again, the calm respect with which ideas were shared. There seemed to be a strong bond of “knowing” between the writers.

Melissa Lucashenko started by sharing some motivational quotes: “we are the authors of our lives” and James Baldwin’s statement that “freedom is not given, you take it.” She said Baldwin’s statement expressed an existential position – don’t wait, take power, and use it wisely.

Alexis Wright

Alexis Wright spoke about Tracker (the subject of her Stella-prize-winning book Tracker) and his focus on sovereignty. He was a visionary, she said, who wanted a stable Aboriginal economy, to ensure a secure culture, a secure future. She, like Lucashenko, emphasised the “sovereignty of the mind.”

She then talked about writing Tracker, which she calls a “collective biography”. She couldn’t do a conventional biography, she said, because he was a community man, because “his archive, his filing cabinet was in the minds of other people”.

There was much discussion about Tracker, who was clearly powerful, and significant in the indigenous community, albeit not everyone always agreed with him. Wright said he was a complicated person, with a sharp mind, which he was happy to express. He said, for example, that Native Title was “not big black stallion but a donkey”.

“Stories, songs, language are sovereign” (Scott)

Scott then talked a little about his latest novel Taboo. He said he tries hard not to think about politics and Aboriginal discourse when he writes his fiction, but he is interested in reclaiming older Noongar narratives and bringing in deeper resonance of place. “Stories, songs, language are sovereign” he said, and communities need to keep them strong so they’ll survive. There has been a long attempt to destroy stories and songs but we are moving from “denigration to celebration”.

Lucashenko raised the issue, currently being nutted out, regarding cultural restrictions on writing about other people’s country. I pricked up my ears of course at this, because it’s related to the cultural appropriation issue concerning white people writing black stories. Lucashenko said when she writes her own country she’s writing with rich knowledge. Writing about anywhere else would be superficial.

Wright was more circumspect about this restriction/limitation. Carpentaria, which is based in her country, was the book she wanted to write, but she is still learning about what she wants to write. Her 26 January story could, she said, be set anywhere.

Scott said he wrote Taboo in the “language of the default country”. He feels accountable to the past, to the fragile massacre area he comes from. He wants to build it up, strengthen its heritage. (He spoke about this in last year’s Ray Mathew lecture.) Perhaps we should all deepen our regions he said.

It was interesting here, because Scott clearly feels the need to strengthen Noongar culture, particularly his own area of it, while Lucashenko believes the culture in her country in northern NSW is strong. She lives in a progressive region, and they have “good white allies”. (See “white allies” discussion in the Q&A.)

Wright said that her country, her people, are strong, making it hard to encourage people into militant fighting for rights.

“Pay attention, tell the truth, write towards power” (Lucashenko)

At this point, Lucashenko teased out more about her notion of sovereignty – which she also expressed in the GR 60 session I attended: it doesn’t have to be politics but “can grow inside our heads.” She then said the job of the writer in these times is to pay attention, tell the truth, write towards power.

Scott suggested that sovereignty of mind involved (included) being accountable to ancestors and descendants. He talked about Australian Renaissance being “not digging up shards of pottery but texts buried in the landscape.”

The writers discussed language, words, and meanings – the importance of unpacking language – around this point. Lucashenko said that the Bundjalung word for river is also the word for story, making the river, in her novel Too much lip a powerful metaphor for stories. Wright said that river means many things in her country too.

Craigie asked whether there was a change in how people are seeing intellectual and cultural sovereignty. Lucashenko seemed positive about young people’s sense of sovereignty within themselves and in their relationship to country, but said the young need to be nurtured with vigilance. She believes the thing is to avoid being reactive, because reaction puts you in a powerless position. She also said it was important not to become distracted by people who “don’t understand us.” Focus, instead, she said, on learning your own civilisation.

Survival

In a way, the whole session was about survival, but around here it came into sharper focus. Wright agreed that young people understand sovereignty and can teach older people about being gutsy. She emphasised the importance of nourishing story, of making story and of keeping it straight. Indigenous people are going to need strong storytellers. We’ve been an oral culture, she said, and need to learn from how the ancestors survived.

Scott agreed that indigenous people need to look after themselves, to “learn the game” (at which point Craigie quoted an African writer on learning to assimilate without assimilating.)

Lucashenko argued that indigenous culture is a knowledge-seeking culture, which is how they have survived. Indigenous people have done what they needed, learnt what they needed – such as learning English – to survive. (This reminded me of my recent Arnhem Land trip, during which we learnt about interactions between indigenous Australians and the Macassans for a few centuries. Indigenous people learnt skills, such as making dugout canoes, and incorporated Macassan words into their languages.)

Lucashenko concluded that indigenous people need to cultivate confidence.

Q & A

One questioner asked an excellent question regarding being good white allies: How best do we consume indigenous stories while preserving their integrity:

- This is the nub, said Scott. There’s no easy answer, but: be conscious, and have a desire to listen. There is a real issue for Scott in getting the balance right to ensure indigenous people aren’t disempowered by non-indigenous people becoming more knowledgeable about culture than indigenous owners.

- Lucashenko said there’s a simple test: Who benefits? If the answer is not the indigenous person, then go away and think again.

There were more questions, but I’ll leave it here – with the reminder to myself to always ask:

Who benefits?

If you are an Australian, you will be aware of our recent Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse. That Commission only looked into one aspect of child sexual abuse in Australia. Arguably the bigger issue lies in the sexual abuse of children outside institutions – abuse of children by family members, by so-called family “friends” and others known to the child, and by, far less common, strangers. The bigger issue also encompasses child abuse that’s not sexual – physical abuse, emotional abuse, neglect, abandonment. This week, September 2 to 8, is National Child Protection Week. Co-ordinated by NAPCAN, it aims to encourage all Australians “to play their part to promote the safety and wellbeing of children and young people” in all ways.

If you are an Australian, you will be aware of our recent Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse. That Commission only looked into one aspect of child sexual abuse in Australia. Arguably the bigger issue lies in the sexual abuse of children outside institutions – abuse of children by family members, by so-called family “friends” and others known to the child, and by, far less common, strangers. The bigger issue also encompasses child abuse that’s not sexual – physical abuse, emotional abuse, neglect, abandonment. This week, September 2 to 8, is National Child Protection Week. Co-ordinated by NAPCAN, it aims to encourage all Australians “to play their part to promote the safety and wellbeing of children and young people” in all ways. Ali Cobby Eckermann, Too afraid to cry: indigenous poet, memoirist and novelist, Eckermann beautifully (if you can use the work “beautiful” in this situation) captures the impact on her of being sexually abused from a young age by an uncle. Not knowing having the words to describe what was happening to her, she can only describe her feelings: it felt like an “icy wind”. This becomes a metaphor for the abuse, for her memory of it, and for its impact on her psyche until she can no longer cry – “the ice block had turned to stone, and now there was no moisture left inside me”.

Ali Cobby Eckermann, Too afraid to cry: indigenous poet, memoirist and novelist, Eckermann beautifully (if you can use the work “beautiful” in this situation) captures the impact on her of being sexually abused from a young age by an uncle. Not knowing having the words to describe what was happening to her, she can only describe her feelings: it felt like an “icy wind”. This becomes a metaphor for the abuse, for her memory of it, and for its impact on her psyche until she can no longer cry – “the ice block had turned to stone, and now there was no moisture left inside me”. Kirsten Krauth, just_a_girl: a modern novel about a 15-year-old girl who thinks she’s more sophisticated than she is, with a mother who is struggling with her own problems. The result is a sexualised young girl at risk.

Kirsten Krauth, just_a_girl: a modern novel about a 15-year-old girl who thinks she’s more sophisticated than she is, with a mother who is struggling with her own problems. The result is a sexualised young girl at risk.

Jenny Ackland

Jenny Ackland