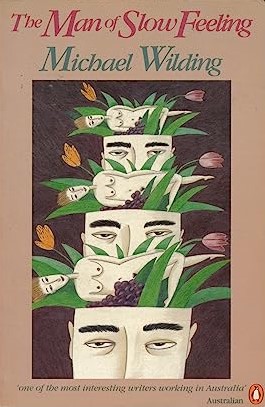

I have had to put aside the novel I was reading for Bill’s Gen 1-3 Aussie male writers week, as my reading group book called. I will get back to it, and post on it later, but in the meantime, I wanted to post something in the actual week.

So, I turned, as I have for other Reading Weeks, to The Penguin century of Australian stories, an excellent anthology edited by Carmel Bird. Given Bill’s week encompasses writers working from 1788 to the 1950s, Bird’s anthology offered almost too many choices. Besides the obvious Henry Lawson, there were Steele Rudd, Tom Collins, Vance Palmer, and more, ending with Judah Waten’s 1950 story, “The mother”. I considered several, but Gavin Casey captured my attention because in her Introduction to the anthology, Kerryn Goldsworthy, looking at the 1930s and 40s, commented that Gavin Casey’s “Dust” and John Morrison’s “Nightshift” exemplified the more overtly political stories of this era. She added that:

they are stories in simple, unadorned language … that focus on workers and workplace disasters, on the physical dangers lying in wait for working men and women.

I have been interested in this period – and its socialist-influenced political thinking – for some time, so it had to be Casey or Morrison. Casey it was because I have listed him in a couple of Monday Musings posts but knew nothing about him.

Who was Gavin Casey?

Casey (1907-1964) was an author and journalist, born in Kalgoorlie, Western Australia, to an Australian-born father and Scottish mother.

He doesn’t have a Wikipedia article but there is a useful biographical entry for him in the Australian dictionary of biography (ADB). Written by Anthony Ferguson, it says he had a sketchy education before obtaining a cadetship with the Kalgoorlie Electric Light Station. However, he left there to work in Perth as a motorcycle salesman, only to be “forced” back to Kalgoorlie in 1931 by the Depression. He then worked “as a surface-labourer and underground electrician at the mines, raced motorcycles and became a representative for the Perth Mirror“. He married in 1933, but “poverty plagued them, long after their return to Perth next year”.

By 1936, he was publishing short stories in the Australian Journal and the Bulletin, and in 1938 he was foundation secretary of the West Australian branch of the Fellowship of Australian Writers. His two short story collections – It’s harder for girls (1942), which won the 1942 S. H. Prior memorial prize and in which “Dust” appeared, and Birds of a feather (1943) – established his reputation. Ferguson writes:

Realistic in their treatment of place and incident, his stories showed—beneath the jollity and assurance of his characters—inner tensions, loneliness, unfulfilled hopes, and the lack of communication between men and women.

You may not be surprised to hear that his first marriage failed!

Overall, he wrote seven novels plus short stories and nonfiction works. His novels include Snowball (1958), which “examined the interaction between Aborigines and Whites in a country town”, and Amid the plenty (1962), which “traced a family’s struggle against adversity”. There is more about him in the ADB (linked above).

Ferguson doesn’t specifically address the political interests Goldsworthy references. Instead, he concludes that critics liken Casey’s earlier works to Lawson, seeing “a consistent emphasis on hardship that is tempered, for the male at least, by the conviviality of mates”. Ferguson also praises both for “their perceptiveness” and “their execution”.

The reality of Casey is a bit more nuanced, I understand. For a start, his men are not bush-men but suburban workingmen. Consequently, I plan to write more on him in a Monday Musings Forgotten Writers post, soon. Meanwhile, on with “Dust”.

“Dust”

“Dust” features male characters only, and there are some mates but, while they are important, they are not central. “Dust” also must draw on Casey’s experience of working in Kalgoorlie’s mining industry. It’s a short, short story, and is simply, but clearly constructed. It starts with a physical description of dust swooping through the township, over housetops and hospital buildings, and “leaving a red trail wherever in went”. It sounds – almost – neutral, but there are hints of something else. Why, of all the buildings in town, are “hospital buildings” singled out with the “housetops”, and does the “red trail” left behind signifiy anything?

Well, yes it does, as we learn in the next paragraph. Although this dust comes from “honest dirt” and can do damage like lifting roofs off, it is “avoidable” and is nothing like the “stale, still, malicious menace that polluted the atmosphere of far underground”. Ah, we think, so the “dust” we are talking about is something far more sinister than that flying around the open air.

And here is where the hospital buildings come in. Protagonist Parker and his miner friends are waiting for their six-monthly chest x-rays checking for the miners’ dust lung disease which killed his father. Things have changed since his father’s times, Parker knows. Not only are there the periodic medical examinations, but there are mechanisms to keep the dust down, and a system of “tickets” and pensions for affected miners. But, the risk is still there, and Parker’s anxiety increases as he watches his mates go in one by one, while he waits his turn.

This is a story about worker health and safety – but told from a personal not political perspective. It’s left to the reader to draw the political conclusions. However, it is also a highly relatable story about humans, health, and risky choices and behaviour, because it seems that Parker does have a choice. I won’t spoil it for you, but simply say that the ending made me smile – ruefully.

Gavin Casey

“Dust” (orig. 1936)

in Carmel Bird (ed.), The Penguin century of Australian stories

Camberwell: Penguin Books, 2006 (first ed. 2000)

pp. 86-90