My Jane Austen group is reading Persuasion – eleven years since we last did it – because 2017 is the 200th anniversary of its publication. Of course I’ve read it several times, so, as you’ll know from my other Austen re-reads, my aim here is to focus on reflections from this read rather than to write a traditional review.

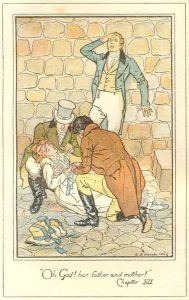

You’ll probably also know that my group often does slow reads of her novels, a volume at a time. Persuasion was published in two volumes, so last month we read Volume One. It finishes at Chapter 12, just after Louisa Musgrove has her fall at Lyme. This post is about this volume.

But first, I want to say something my relationship with Persuasion. I first read it in 1972 when the second TV miniseries was screened in Australia. I was reading it in tandem with the screening, and the night the last episode screened I sat up late to finish the last chapters. I’ll never forget my emotional response to it. I can’t remember whether the miniseries was a good one, but I sure thought the book was. Why?

Persuasion doesn’t have the sparkle of Pride and prejudice, nor the young spoofy humour of Northanger Abbey, nor even the heroine we love to laugh at in Emma, but it is quiet, emotional and deeply felt. Its heroine Anne, at 27 years old, is Austen’s oldest. She’s caring, intelligent, but put upon by her unappreciative family – and yet we don’t feel she’s a pushover. The novel’s romance, when it comes, feels right and well-earned. No-one ever says that Austen should not have married Anne to her man the way some do about some of her other heroines such as Marianne in Sense and sensibility, and Fanny in Mansfield Park. No, when it comes to Persuasion, Austen fans are generally in agreement: it’s a lovely book in which the hero and heroine belong together. But, it’s about so much more too …

I’m not going to provide a summary, so if you need to refresh yourselves on the plot and characters please check Wikipedia.

A specific setting

I’m not sure why it is, but on this my nth (i.e. too many to count) reading of Persuasion, I suddenly noticed that it was the only book, really, that gives us a very specific date and that is set pretty much exactly contemporaneous with when Austen was writing it. It starts in “this present time, (the summer of 1814)” and ends in the first quarter of 1815. This period pretty much covers the hiatus in the Napoleonic Wars when Napoleon was exiled to Elba – and is why Naval Officers are out and about, on land and available for appearing in Persuasion! Sir Walter’s friend and advisor, Mr Shepherd tells him:

This peace will be turning all our rich Navy Officers ashore. They will all be wanting a home.

It is the appearance of the Navy and Austen’s contrasting the substance of naval officers with the superficiality of the aristocracy that gives Persuasion its particular interest – beyond its lovely story, I mean. It is very much a book about social change. (I should say, here, that Austen was partial to the Navy, having two successful Naval brothers)

Two themes

Anyhow, this idea and that relating to persuasion are developed in Volume 1 through various themes, two of which I’ll discuss here.

Appearance and Social status

That social status is a major concern is heralded on the book’s first page when we are told about Sir Walter’s favourite book: “he was a man who, for his own amusement, never took up any book but the Baronetage”. The narrator tells us soon after that:

Vanity was the beginning and the end of Sir Walter Elliot’s character; vanity of person and of situation.

However, he has not been sensible with his money, and needs to rent out his home Kellynch-hall, hence my earlier quote. But, Sir Walter doesn’t like the Navy, and his reasons convey two of the novel’s themes – the focus on status and the cult of appearance. His response to the idea of renting his home to a Naval officer is:

Yes; it is in two points offensive to me; I have two strong grounds of objection to it. First, as being the means of bringing persons of obscure birth into undue distinction, and raising men to honours which their fathers and grandfathers never dreamt of; and secondly, as it cuts up a man’s youth and vigour most horribly; a sailor grows old sooner than any other man …

This is of course ironic, because the naval officer, Admiral Croft, to whom he eventually agrees to rent the place is a thoroughly decent man (who removes Sir Walter’s myriad “looking glasses” when he takes residence). Croft also, Anne “fears”, looks after the Kellynch estate and its people far better than her family did. However, for Sir Walter, the only thing that matters is status.

As the novel progresses, the difference between the Navy and the aristocracy is further developed, but more on that anon.

Anne’s sister Mary is highly aware of her status as a Baronet’s daughter, and the “precedence” due to her. That she stands on this demonstrates her superficiality and lack of decent human feeling. She complains when she goes to her in-laws’ home that her mother-in-law does not always give her precedence. One of her sisters-in-law complains to Anne:

I wish any body could give Mary a hint that it would be a great deal better if she were not so very tenacious; especially, if she would not be always putting herself forward to take place of mamma. Nobody doubts her right to have precedence of mamma, but it would be more becoming in her not to be always insisting on it.

Later, after Louisa’s fall at Lyme, when it is suggested that calm, capable Anne remain behind to care for Louisa, Mary objects:

When the plan was made known to Mary, however, there was an end of all peace in it. She was so wretched, and so vehement, complained so much of injustice in being expected to go away, instead of Anne;—Anne, who was nothing to Louisa, while she was her sister …

Here again is Mary’s misplaced sense of “precedence”. It is also a lovely example of Austen’s plotting, because only a few chapters earlier Mary had refused to stay home from a family party to look after her own injured little boy, preferring Anne do it. Austen had set us up nicely to see the superficiality of Mary’s desire to care for her sister-in-law. The more you read Austen, as I’ve said before, the more you see how fine her plotting is.

Strength of character versus Persuasion (or the influence of others)

Another ongoing issue in the novel concerns strength of character. Captain Wentworth reflects on Anne’s lack thereof in refusing their engagement when she was 19:

He had not forgiven Anne Elliot. She had used him ill; deserted and disappointed him; and worse, she had shewn a feebleness of character in doing so, which his own decided, confident temper could not endure. She had given him up to oblige others. It had been the effect of over-persuasion. It had been weakness and timidity.

A little later, he praises Louisa Musgrove’s strength of mind, but we, the reader, realise her pronouncements are theoretical. She had not been put to the test. She says:

What!—would I be turned back from doing a thing that I had determined to do, and that I knew to be right, by the airs and interference of such a person?—or, of any person I may say. No,—I have no idea of being so easily persuaded. When I have made up my mind, I have made it.

Meanwhile, Louisa shares gossip about Anne, suggesting that Lady Russell, who had discouraged Anne from marrying Captain Wentworth, had also discouraged her from marrying Charles Musgrove (which of course reinforces for Wentworth the idea of Anne’s weakness of character).

… and papa and mamma always think it was her great friend Lady Russell’s doing, that she did not.—They think Charles might not be learned and bookish enough to please Lady Russell, and that therefore, she persuaded Anne to refuse him.

In this case, though, the decision was all the then 22-year-old Anne’s – but Wentworth only hears the gossip.

Henrietta adds to the chorus about Lady Russell’s persuasive power:

I wish Lady Russell lived at Uppercross, and were intimate with Dr. Shirley. I have always heard of Lady Russell, as a woman of the greatest influence with every body! I always look upon her as able to persuade a person to any thing!

You can see Austen building up the plot here, leading us to see Wentworth as unlikely to be interested in Anne again.

Anne, though, sees that firmness of character can go too far, that Louisa’s wilfulness against the advice of others had resulted in her potentially life-threatening fall. She wonders

whether it ever occurred to him now, to question the justness of his own previous opinion as to the universal felicity and advantage of firmness of character; and whether it might not strike him, that, like all other qualities of the mind, it should have its proportions and limits. She thought it could scarcely escape him to feel, that a persuadable temper might sometimes be as much in favour of happiness, as a very resolute character.

Will he see it her way? We’ll have to read Volume 2 to find out!

There’s a lot more I could say, but I think I’ve said enough. Next post I plan to take up the Navy issue a bit more …