Presented in partnership with Sydney Review of Books and Radio National’s The Bookshelf

This was my final session of the festival, and it felt the perfect choice after five sessions focussing on authors and their novels. The program described it this way:

Derided, disparaged and cursed to the heavens, book critics are depicted as literature’s grand villains – as frustrated creators and gleeful wreckers. But what do critics really do? And why are they necessary for a healthy literary ecosystem? James Jiang, Beejay Silcox and Christos Tsiolkas – a trio of Aussie critics – make the case for criticism. In conversation with Kate Evans and Cassie McCullagh (recorded for Radio National’s The Bookshelf).

Again there was no Q&A, because it was being recorded.

The session was conducted jointly by Kate Evans and Cassie McCullagh though the participants didn’t need much guidance as this was a topic they cared deeply about.

Cassie did the acknowledgment of country. The participants were introduced – author Christos Tsiolkas (who has appeared several times on my blog), Editor of the Sydney Review of Books James Jiang, and critic and Canberra Writers Festival Artistic Director Beejay Silcox. Then the discussion commenced. I considered using my usual headings approach but the discussion was so engaged and free flowing, that I decided breaking it up would lose some of the connections. So, I’ve bolded a few ideas here and there as a guide. And, I’ve put my own reflections in parentheses.

Kate leapt right with a question to Beejay about what happens when she “sees the whites of the eyes” of someone she has critiqued. This indeed had happened, Beejay responded, as she had loved one book by Christos and not another! But, if she can’t be honest she shouldn’t be doing the job. She doesn’t feel uncomfortable facing people if she has done her job properly, thoughtfully, respectfully.

Christos admitted that it can be difficult to receive criticism, but he also writes criticism. However, it’s film criticism, because as an Australian novelist he feels he can’t be objective about other Australian novelists. He has critiqued novelists no longer with us, such as Patrick White.

Beejay had been writing criticism out of Australia for seven years before she appeared on the scene, so she didn’t have that issue of being known. (In fact, some thought her name was a pseudonym being used by an author, and Christos was one of the suggestions for that author!)

James, who is ex-academia, believes reviewing living authors offers a “massive opportunity” because you can guide the development of the art into the future. Critical thought, in other words, gets sucked up into the culture at large.

Kate and Cassie, who use reviewers on their radio program, were interested in how you choose who reviews what. Debut authors can sometimes want to make a name for themselves and, for example, love to attack the sacred cows. So, their practice is to give these authors books from other countries to review. They are also conscious of hidden agendas they’d like to avoid, like friends or lovers who had fallen out! (I suspect that working for a national broadcaster that people love to criticise requires a different mindset.)

James, on the other hand, doesn’t mind a gung-ho critic. But he feels that increasingly in Australian letters there is the official story and the backroom chat, with the latter often not appearing in social media. He would like transparency, and wants these informal ideas to make their way into formal criticism.

Christos took this idea up, arguing that criticism is a conversation, an argument, but he likes to know the perspective of the critic, where they are coming from. He thinks Australians are scared of having the debate. He also thinks that to be a good reviewer you need to be a good writer. This came up a few times through the discussion, the idea that good criticism is a work in its own right.

Picking up the idea that Australians are scared of the debate, Beejay suggested that we are a comfortable country but criticism is inherently uncomfortable. She’s been told she is brave, but she’s not. She knows what bravery is and it’s not her. Rather, she is being honest. She worries for our culture if what she does is seen as “brave”. Criticism should open doors, but it is often mistaken for closing things down. (Thinking about bravery versus honesty, I wonder if it’s more about confidence. Confidence in what you think, confidence that you can present it clearly, and confidence that you can defend it.)

Christos talked about loving the American film critic Pauline Kael. She starts by asking what is the work doing, and how is it doing it. But, she has criticised – negatively – films that he loves. So, immediately he is in a conversation with her about why he loves the work, perhaps even despite her criticisms.

Writing schools, Christos said, should teach criticism and how to deal with criticism, because there is a sting to a critical review. He quoted Hemingway’s advice to young writers – don’t compare yourself to the present because you don’t know what will hold, compare yourself to the past. (This is probably good advice for critics too! So many works we read now won’t hold, for reasons that, admittedly, aren’t always due to quality.)

At this point, Kate asked what is good criticism. For her it is not about guiding her on whether to read a book or not. In fact, she said, let’s define criticism!

James suggested that criticism was ultimately a form of ekphrasis. The most interesting reviews are those that “recreate the object of scrutiny”, that “conjure the object”, for the reader. In other words, criticism explores the work itself rather than whether it is better or worse than some other work. So, probed Cassie, it’s not about evaluation but context? Not in a discrete way, James said, but you are evaluating all along. Every process of description contains evaluation. But it’s not plonking some assessment at the beginning or end. (I wrote YES! here, because I often worry that I don’t pronounce enough on my feelings about a book. Today’s session has encouraged me to continue with my preference for trying to work out what a book is doing, rather than focusing on whether I like it.)

Christos suggested that the best way to show you care about the art is to ask why it doesn’t work.

Kate then got to the nub of the word “criticism” which people tend to understand as something negative rather than something more analytical. Beejay took this up, saying that people want to ask about the negative, the “bloody”, but she also looks for awe. It’s about opening a book and being prepared to be drawn in, of watching a mind at work. (This is what most intrigues me when I’m reading: What is the mind behind this doing? Where is it going? Why is it doing this?) Her greatest fear is that she will lose the capacity for awe, to be amazed.

Christos said that it can be hard to write about what gives you the awe. (It can be hard to write about the opposite too, though, methinks?) Beejay suggested that the best critics bring doubt, not certainty. They offer “a (their) theory” about the work.

Christos talked about having trust in the critic (and he gave an example of a music critic he trusts, who works in an area he knows little about).

Asked about bringing in expertise, James made the interesting statement that he wants to estrange experts from their expertise. He talked about the difficulties of public writing – and used The Conversation as an example. Experts tend to dilute their writing for the public so that it ends up being “high advertising” for the university. He wants to get away from that. Good public writing might change the style – from academic – to make it interesting, to engage the reader, but shouldn’t dilute the content. SRB will accept essays from 3000 to 10000 words. He gave the example of a 10000-word essay by a poet on the poetics of videogames. There was a mismatch between the subject (video games) and perspective (a poet) but the the result was something good.

On this expertise issue, Beejay commented that many feel they need to have read everything relevant to be able to comment, but she doesn’t believe that’s so. Christos suggested it was partly generational, and came out of the post-modern era. He had to wash it all off when he left university. (I understand this.)

Beejay on the other hand was a lawyer, not an academic. She left the law, and thought academia was solipsistic, not willing to have conversation. She found criticism by accident. Books saved her life, and now she’s giving back to them. She’s jaded about academia.

James, however, grew up with working class parents, and was looking for where he could go to have the conversations he wanted. He found it in an English seminar. The classroom environment taught him to edit his own writing. (Kate commented that Michelle de Kretser’s latest novel, Theory and practice, feeds well into this discussion.)

The conversation then moved on to the focus on the latest thing, and how to not be “just recent”. Christos said the best festival panels for him are those where they discuss influences and books loved. We need to find space for this because there is the danger that some of what we focus on is just fashion, and that we are being influenced by the language around us. He wishes there were more spaces for reflective pieces. (Being involved in the Australian Women Writers blog, and a Jane Austen group, I don’t disagree with any of this!)

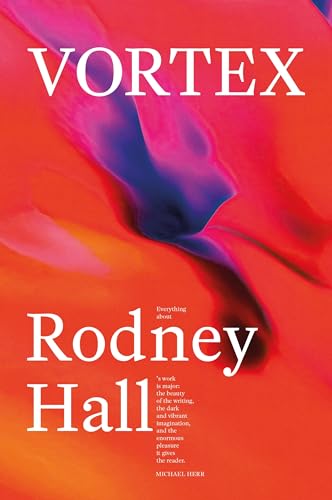

Beejay loves reading favourite writers on how they became who they are. She criticises Australia because she loves it, but we are anglophone and protestant. We have an incredible critical legacy and we forget it. Rodney Hall, for example, has a large body of work but only one book, besides his latest, can be bought in bookshops. Critics can keep older work alive, and the more alive our discourse, the more alive our culture.

Christos agreed, and talked about a community radio session that focuses on the things we love. (The damage done by academia is that there’s no love.)

Cassie wondered about pulling punches, and talked about being told to pull one. Beejay had never pulled punches, but she knows which punches she wants to make. James offered a different angle, suggesting that some things are interestingly bad, whereas others can be good but dull. There’s much good but dull publishing he suggested. Christos talked about being told he should have pulled a punch when reviewing a promising young woman because what she was doing was important. What he’d written was “fair but not right”!

Returning, it seemed, to the idea of evaluation, Kate grapples with “stars”. She’s not good with binaries, but if you’re not binary, are you being nuanced or wishy-washy. (I feel her pain!) Beejay suggested that how she feels is almost irrelevant to the reader, it’s how she thinks that’s important. Feeling can impact thinking, but she has written positive reviews about things she didn’t care for.

Cassie then asked about spoilers. For Christos, to do justice to a work, to get to a conversation about it, he assumes you are interested in the whole, in how it works. James gave the example of classical tragedies. We all know how they are going to end. But then, he said, he is more of a voice and style rather than a plot person. (Yes!) Criticism is an ethical activity, and you need to be brave about owning your idea. (I think I might have missed how this related to spoilers.) Beejay talked about having the trust of her reader and working out when to share what. Criticism is the tip of the iceberg. There is a lot of effort and care beneath it. (This discussion of spoilers missed a significant point that wasn’t addressed at all during the discussion which is whether there is a different between Review and Criticism. I feel there is, and that in reviews spoilers are generally not what readers want, whereas with criticism it’s as Christos said, it’s about the whole and you can’t do that without talking about the end.)

And that was that … have you made it to the end? If so, do you have any thoughts to share?

Canberra Writers Festival, 2024

The case for critics

The Arc Theatre, NFSA

Sunday 27 October 2024, 12-1pm