Once again, I am combining my Nonfiction November weeks because this month has been very busy personally as well as blog-wise.(I did Week 1, on its own, and then combined Weeks 2 and 3).

Nonfiction November is hosted by several bloggers, each one managing one of the weeks. This year, Week 4 – Worldview Shapers is hosted by Rebekah at She seeks nonfiction, and Week 5 – New to my TBR, by Lisa at Hopewell’s Library of Life.

Worldview Shapers

This week the questions relate to the fact that

One of the greatest things about reading nonfiction is learning all kinds of things about our world which you never would have known without it. There’s the intriguing, the beautiful, the appalling, and the profound. What nonfiction book or books have impacted the way you see the world in a powerful way? Is there one book that made you rethink everything? Do you think there is a book that should be required reading for everyone?

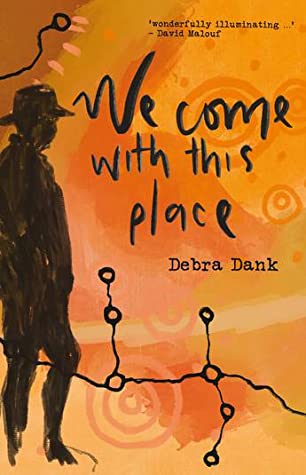

“Everyone” is a big call but I’m going to say it anyhow. I believe that, in the interests of truth-telling (or, is it, truth-receiving) that everyone in Australia should read more First Nations authors, fiction and non-fiction. I have read a few that I’d recommend, starting with this year’s standout read, Debra Danks’ We come with this place (my review), which I have already written about a couple of times this Nonfiction November. As I wrote in my last post, through it, I learnt new things about First Nations history and culture; I better understand this history and culture, particularly in terms of connection to Country; and, as a result, I can better explain and defend my support for First Nations’ people’s fight for fairness.

So, I thought I would add two more books on the topic that I have read in recent years, books that are readable, confronting but also generous in outlook, like Stan Grant’s Talking to my country (my review) and Anita Heiss’s Growing up Aboriginal in Australia (my review). I have read other First Nations nonfiction, but these two provide excellent introductions to the experience of living as a First Nations person in Australia.

Although written by an old-ish white man, my brother Ian Terry, I’d like to add to this list his book published this year, Uninnocent landscapes (my post, review to come), which is part of his truth-telling journey on the impact of colonialism on the Australian landscape, and thus, by extension, on First Nations Australians.

New to my TBR

Our instruction is obvious, to identify any nonfiction books that have made it onto our TBRs through the month (and noting the blogger who posted on that book).

I’m sorry, but I tried very hard not to be tempted as I have a pile of nonfiction books already on my TBR and I’ve read so very few of them this year. I was intrigued though by Patrick Bringley’s All the beauty in the world: A museum guard’s adventures in life, loss and art posted by Frances (Volatile Rune). I love going to museums and galleries, and often wonder about those people who stand guard in the various rooms. Do they like their job? Are they interested in the collections they are guarding? How do they cope with being on their feet for so long? Bringley apparently answers these questions, and many more, including some I hadn’t thought of.

I am also hoping to read in the next few months two recent Aussie nonfiction books, Anna Funder’s Wifedom (which Brona has reviewed), and Richard Flanagan’s just published Question 7. I think that’s more than enough to keep me out of mischief.

A big thanks to the bloggers who ran Nonfiction November this year. I wasn’t as assiduous as I could have been, but I did appreciate reading the bloggers I did get to, and I enjoyed taking part on my own blog in the little way I did.

Any Worldshapers for you? Or, new nonfiction must-reads?