Last Monday, I shared the favourite Fiction and Poetry books that had been chosen by various critics and commentators in a select number of sources. I haven’t always shared the nonfiction choices, though I do think it’s worth doing – so this year I am! I won’t repeat the intro from last week, but I will re-share the sources, having edited them slightly to show those which included nonfiction … and remind you that I’ve only included the Aussie choices.

Here are the sources I used:

- ABC RN Bookshelf (radio broadcaster): Cassie McCullagh, Kate Evans and a panel of bookish guests, Jason Steger (arts journalist and former book editor); Jon Page (bookseller); Robert Goodman (reviewer and literary judge specialising in genre fiction): only shared their on air picks, not their extras which became long

- Australian Book Review (literary journal): selected across forms by ABR’s reviewers

- Australian Financial Review (newspaper, traditional and online): shared “the top picks …to add to your holiday reading pile.” (free briefly, but now paywalled.)

- The Conversation (online news source): experts from across the spectrum of The Conversation’s writing so a diverse list

- The Guardian (online news source): promotes its list as “Guardian Australia critics and staff pick out the best books of the year”.

- Readings (independent bookseller): has its staff “vote” for their favourite books of the year, and then lists the Top Ten in various categories, one of which is adult nonfiction, of which I have included the Australian results.

And here are the books …

Life-writing (Memoir/Autobiography/Biography/Diaries)

- Katherine Biber, The last outlaws (Patrick Mullins, ABR; Clare Wright, ABR)

- David Brooks, A.D. Hope: A memoir of a literary friendship (Tony Hughes-d-Aeth, ABR)

- Geraldine Brooks, Memorial days (Jenny Wiggins, AFR; Susan Wyndham, The Guardian; Readings)

- Bob Brown, Defiance (Readings)

- Candice Chung, Chinese parents don’t say I love you (Readings)

- Robert Dessaix, Chameleon (Tim Byrne, The Guardian) (on my TBR)

- Helen Garner, How to end a Story: Collected diaries (Ben Brooker, ABR; Stuart Kells, ABR; Jonathan Ricketson, ABR; Lucy Clark, The Guardian) (see my posts on vol 1 and vol 2 from this collected volume)

- Moreno Giovannoni, The immigrants (Joseph Cummins, The Guardian)

- Hannah Kent, Always home, always homesick (Kate Evans, ABC)

- Josie McSkimming, Gutsy girls (Amanda Lohrey, ABR)

- Sonia Orchard, Groomed (Clare Wright, ABR)

- Mandy Sayer, No dancing in the lift (Clare Wright, ABR)

- Lucy Sussex and Megan Brown, Outrageous fortunes: The adventures of Mary Fortune, crime-writer, and her criminal son George (Stuart Kells, ABR)

- Marjorie (Nunga) Williams, Old days (Julie Janson, ABR)

History and other nonfiction

- Geoffrey Blainey, The causes of war (rerelease) (Stuart Kells, ABR)

- Ariel Bogle and Cam Wilson, Conspiracy nation (Joseph Lew, AFR)

- Liam Byrne, No power greater: A history of union action in Australia (Marilyn Lake)

- Anne-Marie Condé, The Prime Minister’s potato: And other essays (Patrick Mullins, ABR) (on my TBR)

- Joel Deane, Catch and kill: The politics of power (rerelease) (Stuart Kells, ABR)

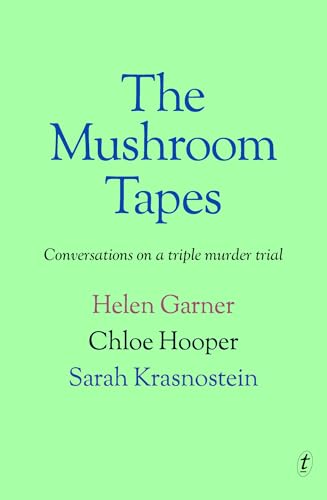

- Helen Garner, Chloe Hooper & Sarah Krasnostein, The Mushroom Tapes (Donna Lu, The Guardian; Readings)

- Juno Gemes, Until justice comes (Mark McKenna, ABR)

- Alyx Gorman, All women want (Sian Cain, The Guardian)

- Luke Kemp, Goliath’s curse: The history and future of societal collapse (Tom Doig, The Conversation; John Long, The Conversation)

- Richard King, Brave new wild: Can technology really save the planet? (Carody Culver, ABR; Clinton Fernandes, ABR)

- Shino Konishi, Malcolm Allbrook and Tom Griffiths (ed), Reframing Indigenous biography (Kate Fullager, ABR)

- Natalie Kyriacou, Nature’s last dance: Tales of wonder in an age of extinction (Euan Ritchie, The Conversation)

- Melissa Lucashenko, Not quite white in the head (Glyn Davis, ABR; Michael Williams, ABR; Readings)

- Ann McGrath and Jackie Huggins (ed), Deep history: Country and sovereignty (Kate Fullager, ABR)

- Tom McIlroy, Blue Poles: Jackson Pollock, Gough Whitlam and the painting that changed a nation (Esther Anatolis, ABR; Alex Now, AFR)

- Mark McKenna, Shortest history of Australia (Patrick Mullins, ABR)

- Djon Mundine, Windows and mirrors (Victoria Grieves Williams, ABR)

- Antonia Pont, A plain life: On thinking, feeling and deciding (Julienne van Loon, The Conversation)

- Margot Riley, Pix: The magazine that told Australia’s story (Kevin Foster, ABR)

- Sean Scalmer, A fair day’s work: The quest to win back time (Marilyn Lake, ABR)

- Emma Shortis, After America: Australia and the new world order (Marilyn Lake, ABR)

- Don Watson, The shortest history of the United States of America (Emma Shortis, The Conversation)

- Hugh White, Hard new world: Our post-American future (Marilyn Lake, ABR)

- Tyson Yunkaporta & Megan Kelleher, Snake talk (Readings)

Cookbooks

- Helen Goh, Baking & the meaning of life (Sian Cain, The Guardian)

- Rosheen Kaul, Secret sauce (Alyx Gorman, The Guardian)

- Thi Le, Viet Kieu: Recipes remembered from Vietnam (Yvonne C Lam, The Guardian)

Finally …

One children’s book, as far as I could tell, was chosen, and I’ve not included it anywhere else so here it is:

- Rae White, with Sha’an d’Anthes (illus.), All the colours of the rainbow (Esther Anatolis, ABR)

A few books were named by two people, with two books named by three, Geraldine Brooks’ Memorial days and Melissa Lucashenko’s Not quite white in the head, and one named by four, Helen Garner’s How to end a Story: Collected diaries. Is it a coincidence that these authors have also written fiction? Or that in terms of my reading wishes, they are up there, though several others are in my sights.

Is there any nonfiction in your sights for 2026? After all, Nonfiction November isn’t that far away if this year is any indication!