Introducing last week’s Monday Musings, I mentioned that the article I was sharing in that post contained a clue to a curly identification I was working on for my upcoming Australian Women Writers blog post. I said that I might share that puzzle this week, and that is what I am doing.

I will get to that soon, but as I also explained last week, that very article that I shared came with its own identification puzzle. That article was signed W.M., and best I cold find was W.M. Kyle, M.A. (or, William Marquis Kyle). He was a loose fit, because while he was a contemporaneous Queenslander, and did write newspaper articles, his interests seemed more philosophy than literature. Fortunately, some of my regular commenters took up the challenge. (How great is this!)

Melanie (Grab the Lapels) posited William Montgomerie Fleming but, while his dates fit, he seems unlikely in terms of his location and focus. I’m glad, though, to add him to my knowledge bank. Meg, however, came up with Winifred Moore, whom she found in Women Journalists in Australian History in a discussion about “the confinement of women journalists to the women’s pages”. Meg wrote that this article said that “under the direction of Winifred Moore from the 1920s, the Brisbane Courier’s ‘Home Circle’ section included a political column of sorts, profiling public personalities in Australia and abroad, alongside the usual recipes and serialised novels.” (You can read more about Moore at the Australian Women’s Register.)

So, of course, I researched Winifred Moore a little more (pun unintended). She wrote the “Home Circle” pages under the pseudonym of “Verity”. But, I also found references to a paper she had given on women writers in 1927 (three years after the article I posted on last week) . So, thanks to Meg, I think there is a good chance that she may be our W.M. I plan to share more on her later. Meanwhile, the original puzzle …

The mysterious J.M. Stevens

I had chosen a story by J.M. Stevens to be my May post for the Australian Women Writer’s Challenge, but, as we find all too frequently, identifying our writers can prove tricky. So it was for J.M. Stevens.

A major source for Australian writers is the (fire-walled) AustLit database and I was delighted to find that J.M. Stevens did have an entry there. It gave me some of her background, including her parentage, and identified an apparently better-known sister as Maymie Ada Hamlyn-Harris, who was a writer and convenor of the Lyceum Club literary circle. It also said that Stevens married John Frederick Stevens around 1917 which means, of course, that her last name stayed the same.

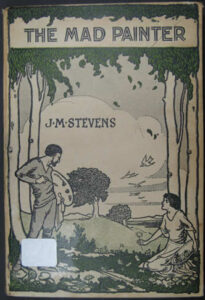

Austlit gives her dates as 1887 to 30 May 1944, and uses J.M. Stevens as their name heading for her. They add that she also wrote under other names: Joan Marguerite Stevens, Janie M. Stevens, Joan M. Stevens. The University of Melbourne’s Colonial Australian Popular Fiction digital archive agrees with Austlit’s dates, but uses Janie M. Stevens as their name heading. They list one book for her, The mad painter and other bush sketches, by J.M. Stevens.

All well and good. It seemed pretty straightforward, but I like to find more if I can and this is where things came a bit unstuck because on 31 May 1944, Brisbane’s The Telegraph reported on the death of Mrs Joan M. Stevens. It says:

Mrs Joan M. Stevens, whose death look place yesterday afternoon at her home, Bylaugh, Glenny Street, Toowong, had been an invalid for many years. She was the fifth daughter of the late Mr E. J. Stevens MLC and the late Mrs Stevens, and had lived practically the whole of her life in Brisbane and Southport. Mrs Stevens was gifted musically, showed considerable talent as a painter and like several members of her family possessed distinct literary gifts, two of her books having been accepted for publication in the south. The late Mrs Stevens, who was the wife of Mr John F. Stevens, is survived by her husband, one daughter, three sons, and one granddaughter. Mrs Stevens was the third sister in the same family to die within six months; Miss Alys Stevens died in November last in Melbourne, and her eldest sister, Miss J. M. Stevens, died in Brisbane a few weeks ago.

So, this seems like “our” J.M. Stevens – same death date, and married to Mr John F. Stevens. But, they also mention a sister, “Miss J.M. Stevens”. Oh oh! Who is this? Three months later, on 17 August, this same newspaper announced the posthumous publication of a novel This game of murder, and says it

was written by the late Joan M. Stevens (Mrs J. F. Stevens), whose death took place a short time ago. The late Mrs Stevens, who was the fifth daughter of the late Mr E. J. Stevens, MLC, a former managing director of the “Courier,” belonged to a literary family. Her sisters included the late Miss J. M. Stevens, the writer of short stories and nature studies, whose death occurred earlier in the year. Another sister is Mrs M. Hamlyn-Harris, who has published several books of verse.

Now, AustLit had said that J.M. Stevens (remember, aka Joan M. Stevens and Janie M. Stevens) was a freelance journalist, with articles and short stories appearing in the leading magazines and weeklies in Australia and New Zealand in the earlier part of her life. In her later years, it says, she wrote a long series of nature studies for the Sunday Mail.

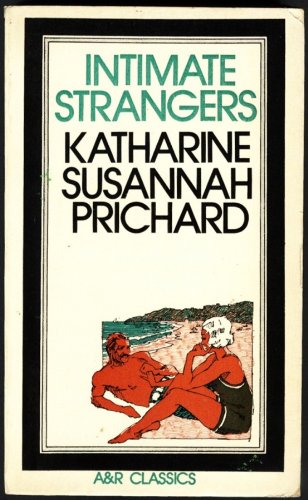

I was starting to feel confused. We have a Mrs. J.M. Stevens and a Miss J.M. Stevens. We have a Joan M. Stevens and a Janie M. Stevens. And it seems that despite AustLit’s entry, they are not the same person, but sisters who both wrote. We know that Joan wrote This game of murder, but who wrote The mad painter and other bush sketches? The cover says J.M. Stevens. It sounds like a nature-related work – the sort of writing that Miss J.M. Stevens did. Certainly Brisbane’s The Week writing about this book on 7 January 1927 describes its author as “Miss Stevens … nature lover and also something [of] a humorist”.

Then I found it! The Brisbane Courier, in an article on Queensland writers on 15 October 1927 identifies Janie Stevens as The mad painter’s author. So, clearly we have two sisters here with the initials J.M. One (Miss Janie) wrote The mad painter, and the other (Mrs Joan) wrote This game of murder. The life dates (at least, the death date) given by AustLit for J.M. Stevens and the Colonial Australian Popular Fiction archive for Janie Stevens, are for Joan. I have shared all this with the AustLit researchers who are always happy to receive feedback. Their challenge now, besides confirming my deduction, will be to identify who wrote which of the newspaper articles ascribed to J.M. Stevens!

I really should be doing more reading …