About a third of the way into Kim Scott‘s novel That deadman dance is this:

We thought making friends was the best thing, and never knew that when we took your flour and sugar and tea and blankets that we’d lose everything of ours. We learned your words and songs and stories, and never knew you didn’t want to hear ours.

And, it just about says it all. In fact, I could almost finish the post here … but I won’t.

That deadman dance is the first Indigenous Australian novel I’ve read about the first contact between indigenous people and the British settlers. I’ve read non-Indigenous Australian authors on early contact, such as Kate Grenville‘s The secret river, and I’ve read Indigenous authors on other aspects of indigenous experience such as Alexis Wright‘s Carpentaria and Marie Munkara’s Every secret thing. Kim Scott adds another perspective … and does it oh so cleverly.

The plot is pretty straightforward. There are the Noongar, the original inhabitants of southwest Western Australia, and into their home/land/country arrive the British. First, the sensitive and respectful Dr Cross, and then a motley group including the entrepreneurial Chaine and his family, the ex-Sergeant Killam, the soon-to-be-free convict Skelly, the escaped sailor Jak Tar, and Governor Spender and his family. The novel tracks the first years of this little colony, from 1826 to 1844.

That sounds straightforward doesn’t it? And it is, but it’s the telling that is clever. The point of view shifts fluidly from person to person, though there is one main voice, and that is the young Noongar boy (later man), Bobby Wabalanginy. The chronology also shifts somewhat. The novel starts with a prologue (in Bobby’s voice) and then progresses through four parts: Part 1, 1833-1836; Part 2, 1826-1830; Part 3, 1836-1838; and Part 4, 1841-44. And within this not quite straight chronology are some foreshadowings which mix up the chronology just that little bit more. The foreshadowings remind us that this is an historical novel: the ending is not going to be fairytale and the Indigenous people will end up the losers. But they don’t spoil the story because the characters are strong and, while you know (essentially) what will happen, you want to know how the story pans out and why it pans out that way.

What I found really clever – and beautiful – about the book is the language and how Scott plays with words and images to tell a story about land, place and home, and what it means for the various characters. His language clues us immediately into the cross-cultural theme underpinning the book. Take, for example, the words “roze a wail” on the first page:

“Boby Wablngn” wrote “roze a wail”.

But there was no whale. Bobby was remembering …

“Rite wail”.

Bobby already knew what it was to be up close beside a right whale …

Whoa, I thought, there’s a lot going on here and I think I’m going to enjoy it. Although Bobby’s is not the only perspective we hear in the book, he is our guide. He is lively and intelligent, and crosses the two cultures with relative ease: just right for readers venturing into unfamiliar territory. He’s a great mimic, and creates dances and songs. The Dead Man Dance is the prime example. It’s inspired by the first white people (the “horizon people”) and evokes their regimented drills with rifles and their stiff-legged marching. There’s an irony to this dance of course: its name foretells while the dance itself conveys the willingness of the Noongar to incorporate (and enjoy) new ideas into their culture.

In fact there’s a lot of irony in the novel. Here is ex-Sergeant Killam:

Mr Killam was learning what it was to have someone move in on what you thought was your very own home. He thought that was the last straw. The very last.

And who was taking his land? Not the Noongar of course, but the Governor … and so power, as usual, wins.

The novel reiterates throughout the willingness – a willingness supported, I understand, by historical texts – of the Noongar to cooperate and adapt to new things in their land:

Bobby’s family knew one story of this place, and as deep as it is, it can accept such variations.

But, in the time-old story of colonisation, it was not to be. Even the respectful Dr Cross had his blinkers – “I’ve taken this land, Cross said. My land”. And so as the colony grew, women were taken, men were shot, kangaroos killed, waters fouled, whales whaled out, and so on. You know the story. When the Noongar took something in return such as flour, sheep, sugar, they were chased away, imprisoned, and worse.

I’d love to share some of the gorgeous descriptions in the book but I’ve probably written enough for now. You will, though, see some Delicious Descriptions in coming weeks from this book. I’ll finish with one final example of how Scott shows – without telling – cultural difference. It comes from a scene during an expedition led by Chaine to find land. They come across evidence of a campsite:

You could see where people camped – there was an old fire, diggings, even a faint path. Bobby was glad they’d left; he didn’t want to come across them without signalling their own presence first, but Chaine said, No, if we meet them we’ll deal with them, but no need to attract attention yet.

Need I say more*?

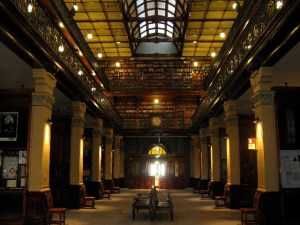

The book has garnered several awards and some excellent reviews, including those from my favourite Aussie bloggers: Lisa (ANZLitLovers), the Resident Judge, the Literary Dilettante, and Matt (A Novel Approach). Our reviews differ in approach – we are students, teachers, historians, and librarian/archivists – but we all agree that this is a book that’s a must to read.

Kim Scott

That deadman dance

Sydney: Picador, 2010

400pp.

ISBN: 9780330404235

* I should add, in case I have misled, that for all the truths this novel conveys about colonisation, it is not without vision and hope. It’s all in the way you read it.