Another preamble

What I didn’t say in my first post on this year’s festival is that the venue where I attended the sessions today is a favourite of mine – and not only because it’s where I spent most of my working career. This year, some strands of the festival are being held at the National Film and Sound Archive, which has two beautiful theatres – the big Arc theatre and the gorgeous, cosy Theatrette. I love the Theatrette, which was carefully refurbished around a decade ago to meet modern needs but retain its heritage art deco style and fittings.

History repeating

I chose this session because it featured two authors I have read, and was about historical fiction which – I’m going to say it – in its more literary form, interests me greatly. The session was described in the program as:

Catherine McKinnon has woven her new book around Robert Oppenheimer and his wife Kitty – the ultimate nuclear family; Emily Maguire’s new novel is an audacious portrait of an audacious woman – a mystery from the Middle Ages. Rebecca Harkins-Cross joins these dauntless storytellers to discuss the narrative lure of historical legends, and what the past can tell us about our present.

I have read Catherine McKinnon’s clever Storyland (my review) which took us from the early days of the Australian colony far into a dystopian future, and Emily Maguire’s not-quite crime fiction, An isolated incident (my review). (Interestingly, my 2022 post on an essay by Emily on Elizabeth Harrower’s short story, “The fun of the fair”, is among my most popular posts this year.)

Anyhow, Rebecca Harkins-Cross commenced by acknowledging the traditional owners of the land on which we were meeting, then shared a quote from McKinnon’s book:

When Robert [Oppenheimer] works, there is seemingly no intrusion from the past into the present. But this, he knows, is illusory. The past shapes the present, creates the future. If thoughts are a trinity of past, present and future, losing the past means obscuring the future. (p 21)*

On its own, this idea is not especially new or dramatic, but it nicely framed the discussion we were about to have.

She then went on to briefly summarise Emily Maguire’s and Catherine McKinnon’s new books, Rapture and To sing of war. Rapture is set in the ninth century and tells the story of a young girl who, at the age of 18, to avoid the usual life for a woman as wife or nun, enlists the help of a lovesick Benedictine monk to disguise herself as a man and secure a place at a monastery. This story was inspired by Pope Joan.

To sing of war, on the other hand, is a polyphonic story set in December 1944 – in New Guinea, with a young Australian nurse who meets her first love, Virgil Nicholson; in Los Alamos, with two young physicists Mim Carver and Fred Johnson who join Robert Oppenheimer and his team “to build a weapon that will stop all war”; and in Miyajima, with Hiroko Narushima who helps her husband’s grandmother run a ryokan.

These two novels are set far apart in place and time but they have, said Rebecca, some unexpected parallels – plucky women confronting a patriarchal society, an interest in the natural world and the sustenance it can offer, and the lives of ordinary people.

She then asked her first question which concerned the idea that with every novel writers often say they have to start anew. Is this how Emily and Catherine felt?

Emily said yes, because her previous novels are contemporary, so while she wanted to write this story it was a challenge. Her method was to stop thinking about it as historical fiction but to focus on the main character and her experience – because she is living in her “now” – and then sort out the necessary details.

Catherine also said yes, that with every new project you feel like a baby again. She looked to Pat Barker’s Regeneration trilogy, not because it’s the same subject, but for how Barker made her era feel like now.

This led Rebecca to ask Emily whether any historical fiction writers were a guiding light for her? Hilary Mantel looms large, she said, and she loves her work, but she wanted to write something shorter, tighter, something pacy. She turned most to Angela Carter, not an historical fiction writer, for how she handles this and for the carnality of her language. She also looked to Danielle Dutton’s Margaret the First, not for her language but for her pacing.

On why their topics

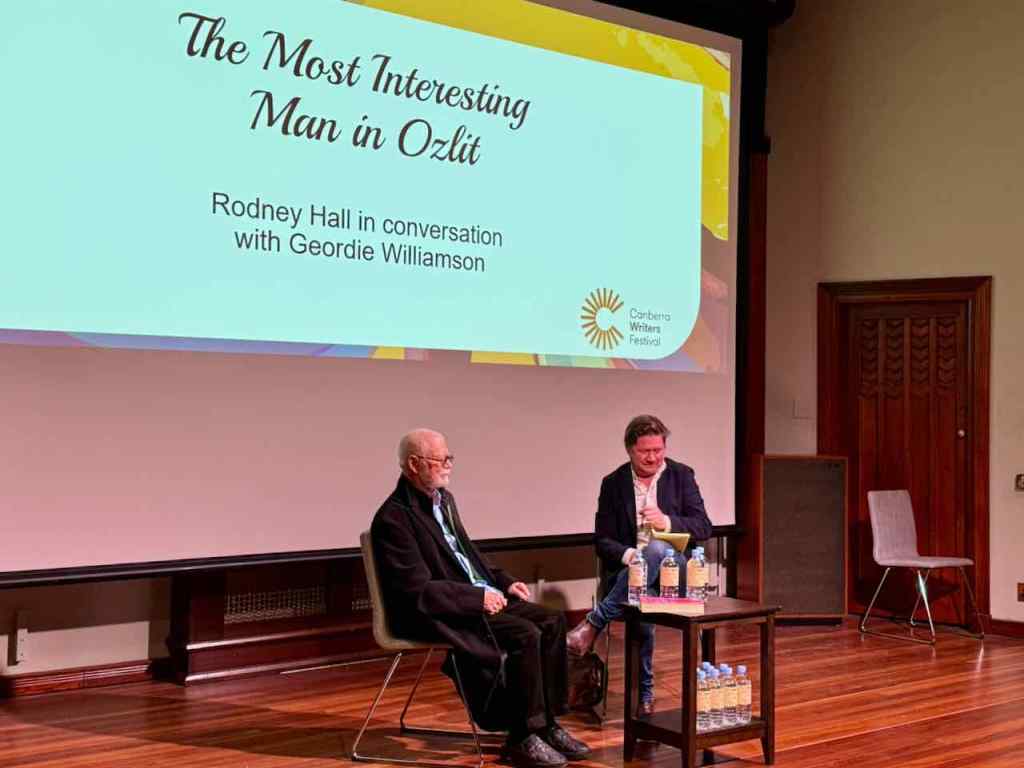

Rebecca, who mixed her questions up for the different authors, then asked Catherine why she’d chosen her particular period and those series of events. Catherine was interested in understanding our governments and the decisions they make. Also in what happens to the land we are on. In World War II, a global war, who were we trusting to make decisions? (This reminded me of Rodney Hall in the morning session and his point about what was being hatched that would affect us later.) She was also interested in who became leaders, in the decisions being made by young people, in the bomb and its impact on the land – and more. Her interest is cultural.

Turning then to Emily, Rebecca wanted to know why she’d chosen the story of the female pope which is now accepted as apocryphal. Emily had come across the story due to her interest in early Christianity, and how it had grown from a small desert cult to a big power. She was interested in this story which most people believed from 1200 to 1600 until the Reformation protestants started questioning Roman Catholicism and its promotion of this story.

But, continued Rebecca, why this particular story? It’s a trickster story, said Emily, and she’s interested in Christianity and the idea of belief vs faith. Her Agnes is a genuine believer. Emily is interested in people’s own beliefs regardless of what the institution is telling them, and in Agnes being in a position where she had to either deny her faith or her femaleness.

At this point Emily did a reading, from early on when Agnes recognises the “bloody service [aka breeding] required of girls”. (This reminded me of Jane Austen who, centuries later, shows, in her letters, acute awareness of what motherhood means for women, including death. She was not impressed or keen!) Emily talked about how she got into Agnes’ character, which included trying to read what she would have been reading – things like the lives of saints. Many of these were violent, including that of her namesake, St Agnes, whose body and purity were deemed more important than her life.

On research

Back to Catherine, Rebecca about her research. She did the common thing – too much! And started by including too much in her book. She went to New Guinea, and spoke to people whose families experienced the war, and researched the botany. She went to Japan – to Hiroshima and the Peace Park and Museum, and to Nagasaki. She read and spoke to people there. She went to America, where she followed the Oppenheimers’ life, and then specifically to Los Alamos and Alamogordo, looking at the desert landscape. She wanted to connect the horror of war with the beauty of the landscape.

She then did a reading, from the opening of the novel.

Rebecca asked Emily how she’d approached research as a novelist, that is, how she balanced doing enough research while leaving space for the imagination.

Emily’s challenge was needing to balance the myth and history surrounding her origin story – Pope Joan. She managed it by keeping tightly focused on the character, on what kind of person is she. She also kept in her head Elie Weisel’s comment that there’s a difference between a book that is 200 pages at the beginning and one that starts at 800 pages and ends up at 200. She started with a much longer draft, which had a lot of scaffolding which she gradually tore down as it was no longer needed. When the novel was well along, she gave it to her first reader, and asked whether there were bits that didn’t make sense because she’d taken too much out, and, conversely, if there was information still in that wasn’t needed.

On their writing choices

Asked about finding Agnes’ voice, Emily said she’d started first person, but it felt right when she turned to “deep third person”. She tried to keep the language to words with Germanic and Latin origins, and she was careful about concepts, metaphors, similes. Something can’t feel “electric”, or can’t “evolve”, for example, in the ninth century!

One choosing her polyphonic structure, Catherine said that the polyphonic or braided novel has been around for a long time. Look at Chaucer’s Canterbury tales. Certain stories call for it, like her interest in small lives in a global world. She wanted a young woman in Los Alamos. She wanted to retrieve New Guinean history because at the time the people were not named. And so on. Her challenge was to find a way to keep the reader interested while jumping from story to story.

And, on history

This led to a question about history and revisionism. What had been written out of the history books that they wanted to return? Emily wanted to show that women could be intellectual forces, be present, be visible, that, just like the present, different women could have different interests and ideas. She wanted to imagine these women into being. I appreciated this response because readers often see such individuals is anachronistic, but I’m with Emily. Intellectual women, feminist women, and so on, don’t pop out of thin air. They have just been hidden.

Similarly, Catherine wanted to bring woman to the fore as thinkers, as scientists, etc, not only as nurses. She wanted to tell of ordinary people, to share queer stories. In other words, she likes finding the hidden stories, and searching out what is kept secret (in societies, and personally). What are the inner emotions, drivers, experiences that frame actions?

Q & A

On Catherine’s inspirations for her characters: Mim was based on a few women who were chemists and mathematicians; Fred was based on a real person called Ted Hall, who worried about America having a monopoly on bomb after war.

On negotiating telling one’s story against big presences like Hilary Mantel’s grand, involving historical novels, and Prometheus Unbound (which was adapted into the film Oppenheimer):

- Catherine didn’t know the film was coming out, but she did use American Prometheus in her research. However, you look for the story you want to tell now – at what is it about now that you want to speak to, at what is it about humans that is interesting to us now. American Prometheus , she felt, was about how people could be picked up and then dropped, but she is interested, for example, in how decisionmaking can be petty. Writers have control over what they see, over their version of it.

- Emily said that “anxiety of influence” is part of being an author, but she has a set of touchstones – such as Angela Carter for this book – of things you admire but that aren’t doing what you are doing. Other Pope Joan stories, for example, have “truth” agendas, but that wasn’t her interest/angle.

I enjoy hearing historical fiction writers talking about what they do because it’s a challenging but, worthwhile, endeavour. This thoughtful session was capped off by my having a delightful private chat with author Robyn Cadwallader (my posts), who had also been in the audience, about some of her historical fiction writing experiences.

* Thanks to Robyn for providing this quote.

Canberra Writers Festival, 2024

History repeating

Friday 25 October 2024, 12:30-1:30pm