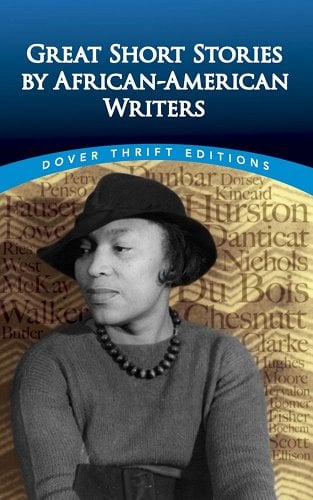

Paul Laurence Dunbar’s short story “The scapegoat” is the fourth in the anthology Great short stories by African-American writers, which my American friend Carolyn sent me. Compared with the previous author, Gertrude H. Dorsey Browne, Dunbar is much better known.

Paul Laurence Dunbar

The biographical note at the end of the anthology provides good background, and Wikipedia has a detailed article on him. Dunbar (1872-1906) was, says Wikipedia, “an American poet, novelist, and short story writer of the late 19th and early 20th centuries”, and “became the first African-American poet to earn national distinction and acceptance”. In fact, it is through his poetry, which is frequently anthologised, that I recognised him when he popped up in the book. He was born in Dayton, Ohio, to parents who had been slaves. Indeed, his father had escaped slavery before the Civil War ended, and fought with the Union Army.

Dunbar, says Wikipedia, wrote his first poem when he was six, and gave his first public recital at nine. Both sources say he was the only African-American in his high school. He was apparently well-accepted, being elected president of the school’s literary society, as well as being the editor of the school newspaper and a debate club member.

Wikipedia provides much detail about his work and publishing history, his health issues (particularly with tuberculosis which killed him), and his failed marriage to Alice Ruth Moore, whose story, “A carnival jangle” (my review), opened this anthology. He was a prolific writer, and was famous for his use of dialect, although he also wrote in standard English. Recognised in his own time, his influence and legacy continues. Maya Angelou titled her book I know why the caged bird sings, from a line in his poem “Sympathy“. But I will conclude with an assessment from his friend, the writer James Weldon Johnson (1871-1938), who wrote in his 1922 anthology, The book of American Negro poetry:

He was the first to rise to a height from which he could take a perspective view of his own race. He was the first to see objectively its humor, its superstitions, its short-comings; the first to feel sympathetically its heart-wounds, its yearnings, its aspirations, and to voice them all in a purely literary form.

We see some of this in the short story chosen for this anthology.

“The scapegoat”

“The scapegoat” is the opening story in Dunbar’s 1904-published collection The heart of Happy Hollow. My anthology describes it as “Dunbar’s story of an ambitious and intelligent young man who sees no reason to sell himself short or accept defeat”. This is accurate, but only half the story.

It is told in two parts, the first before the protagonist Mr Robinson Asbury goes to prison, and the second after his release. The opening paragraph, after referencing the saying that the law is “a stern mistress”, chronicles young Asbury’s fast rise from a bootblack, through porter and messenger in a barber shop, to owning his own shop. The second and third paragraphs describe the story’s setting, the “Negro quarter” of “the growing town of Cadgers”. Here Asbury sets up his barber shop, and attracts customers with his ‘significant sign, “Equal Rights Barber Shop”‘, which our third person narrator says

was quite unnecessary because there was only one race about to patronise the place but it was a delicate sop to the peoples vanity and it served its purpose.

Whatever the reason, he was successful, and his shop became “a sort of club”, where the men of the community gathered to socialise and discuss the news. As a result Asbury soon comes to the notice of “party managers” who, seeing his potential to win them black votes, give him money, power and patronage. This Asbury accepts, and his power and status in the community grows. He then decides he’d like to join the bar, which, with the help of the white Judge Davis, he does.

And so the story continues. With success, he does not “leave the quarter” to “move uptown” as expected, though Judge Davis is prescient:

“Asbury,” he said, “you are–you are–well, you ought to be white, that’s all. When we find a black man like you we send him to State’ prison. If you were white, you’d go to the Senate.”

By now, Asbury’s success is arousing jealousy among his peers, particularly at a local coloured law firm. Two, Bingo and Latchett (great names eh?), are alarmed by Asbury’s fast rise to the top, but his putting out his shingle is “the last straw”. They plan to pull him down, and engage the services of another to lead an opposing faction in the community. However, with the continued help of the “party managers”, Asbury holds the day.

Now politics is messy, and allegiances switch. Along the way Bingo comes over to Asbury’s side. There’s an election, and Asbury’s side wins, but our narrator says:

the first cry of the defeated party was, as usual, “Fraud! Fraud!”

Was there fraud? Certainly there’s intimation of skulduggery, but without evidence it’s decided a “scapegoat” must be found – a big man – and so Asbury is deserted by the party “Machine”, and by his peers including Bingo, and charged. After the jury finds him guilty, Asbury seeks leave to make his statement, which Judge Davis allows:

He gave the ins and outs of some of the misdemeanours of which he stood accused showed who were the men behind the throne. And still, pale and transfixed Judge Davis waited for his own sentence.

It doesn’t come, because Asbury recognises Davis as “my friend”, but he exposes “every other man who had been concerned in his downfall”. He is sent to prison, for the shortest sentence the Judge can give, and is away for ten months, just long enough for him not to have been forgotten and, in fact, to be recognised as “the greatest and smartest man in Cadgers”. (This rehabilitation of Asbury in the eyes of the community while he is absent is just one of the many astute insights Dunbar makes about the way humans think and behave.) Part Two details Asbury’s revenge, but you can read it for yourself at the link below.

“The scapegoat” is a well-written, well-structured story set primarily within the black community, though the “party managers” who want the “black vote” are clearly white. Its main theme concerns political ambition and corruption, and racial oppression. It shows Asbury’s peers working to bring him down, putting their own ambition ahead of the good of the community, and overlays this with oppression by the string-pulling “Machine” uptown. I particularly liked the measured, neutral tone Dunbar employs which, together with his frequent insights into political behaviour and human nature, enables this story to read almost like a fable, a morality tale that says something in particular about this community, about the unfortunate behaviour of people who should support each other, but also something universal about politics and oppression.

It’s unemotional, clever, true – and, unfortunately, still relevant.

Paul Laurence Dunbar

“The scapegoat” (first published in The heart of Happy Hollow, 1904)

in Christine Rudisel and Bob Blaisdell (ed.), Great short stories by African-American writers

Garden City: Dover Publications, 2015

pp. 45-56

ISBN: 9780486471396

Available online (you can find the whole collection at this site)

I can see nothing else to say than plus ça change …

Unfortunately, MR, I think you are right.

I am curious about the quote you’ve shared, the “unnecessary” specification of the “equal rights” barbershop. Whether you have the sense that the third-person narrator actually does believe it’s important to make this specification, or believes that it’s an empty gesture. I think that kind of small detail is outlandishly important in the context of a group that’s been persistently and relentlessly persecuted, even if the only audience is others in that community. The kind of quiet resistence that Saunders identifes in those Russian stories that Bill and Bron and I were reading over a few months earlier this year. But I know everyone has their own beliefs about what constitutes resistance and about what’s effective in the face of persecution.

Good question Marcie. This story is truly rich in what it doesn’t say – in a way. It leaves a lot open to interpretation I felt. And this sign is one of them. Is there a clue to its meaning in “it was a delicate sop to the peoples vanity”. I think the narrator is indicating Asbury’s political and business nous (he does what he thinks will work), but also his commitment to his community (because he never does leave it despite success). It makes them feel good that they are coming to a place that welcomes all, that doesn’t make them feel lesser, and Asbury recognises that. But it’s also probably an aspirational point. This is how Asbury thinks things should be? We come to an understanding of his character through what he does rather than in that the people of that quarter like to think they are open?

I think the action could be seen as quiet resistance, as in I’m not segregating my business. My sense is that the narrator is descriptive of and observational about humanity rather than judgemental.

Thank you for that fascinating information about the author’s life and particularly for that detail about his connection to Maya Angelou. My first impression of the short story was that it took place in an almost completely segregated world– which was why that description of the “equal rights” barbershop delivered such a punch. Yes, some things never change, but I still have a tiny bit of hope that they will….

Thanks Carolyn. It’s a really interesting story that I thought a lot about. Ashbury lives/works in a segregated area I think because we are told it’s the “Negro quarter”. Is the sign partly aspirational … encourage people to come in? Also indicative of Asbury’s beliefs?

I kept rereading this because I couldn’t be sure of the race point. The only white person mentioned is the Judge but it does seem that he is part of the “party managers” and “Machine” and that they are white. They want “the black vote”. Are we supposed to just know they are white because at the time that’s how it would have been? Or does Dunbar keep it obscure to make points about politics regardless of colour? I decided though that Dunbar was implying that Davis wasn’t the only white man but was also saying that political skulduggery isn’t confined to race.

When I lived in Ft Myers Florida, Paul Dunbar was celebrated there . As in the name of an area where African Americans lived. There was a Dunbar street. I once found some first published sheet music written by Dunbar. At least the lyrics, can’t remember about the music. I gave it to an African American friend of mine who was involved in their local museum. His name came up a lot.

In Florida Pam? That’s interesting, but I suppose we honour people in places that aren’t necessarily where they lived, so why am I surprised?

Wikipedia says he wrote the lyrics for the musical comedy In Dahomey. He may have written more too. I’m glad you gave it to a friend for a museum.

He must have had some connection to southwest Florida as his name was very popular. Most African American families began life in the south and then spread out more as slavery ended. Not sure.

Thanks Pam – and for your email explaining this Florida aspect.

I read this a few days ago but without a ready response. What struck me most was his cynical tone, as though politics was always ruled by Tammany Hall, which of course may be true. But I (naively no doubt) was expecting something more upbeat from such an early writer.

I agree that the tone stands out, Bill. I liked it l … I suppose it was cynical. I guess I just saw it as realistic or true! Consequently I wasn’t expecting anything more upbeat. It’s intriguing to me that you did because I think things were worse then. Not that they are great now.

That quote about what the folks would do if a person was black versus white is chilling, and it’s so blatantly prejudice. It just seems like someone would rub two brain cells together and realize how stupid they sound. I also noticed that part about the other black folks trying to pull the main character down. I’m not sure if you knew this, but the name for that is crab theory. We talk about it in both the Deaf community and the interpreting profession. Well, with interpreting, the phrase used more often is “eat our young,” but there is a lot of people putting each other down, which I sadly see in a Facebook group called Discover Interpreting. Lastly, I like the comment about Dunbar employing a neutral tone. I think there is another writer who excels at that: James Baldwin. Baldwin can write a character so unlike himself because he knows that person intimately, for instance in the short story “Going to Meet the Man” for which the narrator is a racist white police officer. I wonder if Bill has read that story, and what he thinks (because he doesn’t want to read fiction written by someone unlike the author him/herself).

Also, I’ve read ALL of Dunbar’s poems (the collection is free online) but non of his fiction!

Loved this response Melanie. What you call crab theory (which I hadn’t heard of) sounds like something well-known in Australia … but we call it Tall Poppy Syndrome, which is the desire to cut down anyone who rises above the rest of the field. There’s a Wikipedia article on it.

Thanks for the recommendation of Baldwin. I know him of course but have read very little of him. I should try some short stories.

Apparently, crabs in a bucket pull down any crab that tries to get out. I like the sound of Tall Poppy Syndrome. I can picture a plant but have never encountered a bucket full of crabs.

Haha Melanie … same here!