In yesterday’s post on Percival Everett’s James, I didn’t discuss the issue of naming. I should have, however, as it is a significant aspect of the novel, so much so that the novel ends on exactly that point. Throughout the novel, James, who is called “Jim” by the “massas” (aka masters) if they bother to call him anything, clarifies that he is James:

“I am James.”

“James what?”

“Just James.”

[end of novel]

Names, as we know, can be tools used for power and control, to dehumanise people. It happens in the most subtle ways, as well as in sanctioned ways. Throughout the colonial project, for example, naming has been used a tool of ownership and submission, but it has also been used to dehumanise and control in all sorts of other legitimated ways, such as in the practice of giving prisoners numbers and calling them by that number.

I was horrified to witness a misuse of a name during our recent trip to Far North Queensland with a company called Outback Spirit. This company makes a practice of using local guides wherever possible, and in remote regions those guides are often First Nations People. It is such a privilege to spend time with those who know the country so well and are prepared to share their knowledge with us. And so it was on our little expedition to stand on the top of mainland Australia.

Our guide was Tom, who identified himself as a Gudang man (with several other familial connections in the region). On our return from Pajinka (their preferred name for the top or point), he lead us across the rocks to the beach and thence our bus. I was in the group right behind him, when we met three middle-aged guys on the way up. The one in front saw Tom and gestured for him to stop. Then, without asking permission, he took a photo (as if Tom was some exotic!) Tom was impressively gracious and, when the guy finished, introduced himself as Tom and welcomed them to country. They seemed to appreciate this – but twice in the very brief conversation that followed, the photographer addressed Tom as “Tommy”. Really? I could be generous and assume that he was one of those people who automatically uses a diminutive form of a name when they are introduced to another person, and I will never know, but it felt so wrong. Whatever the man’s intentions were in using “Tommy” – and whether they were conscious or not – it was a shocking reminder to me of how far we have to go.

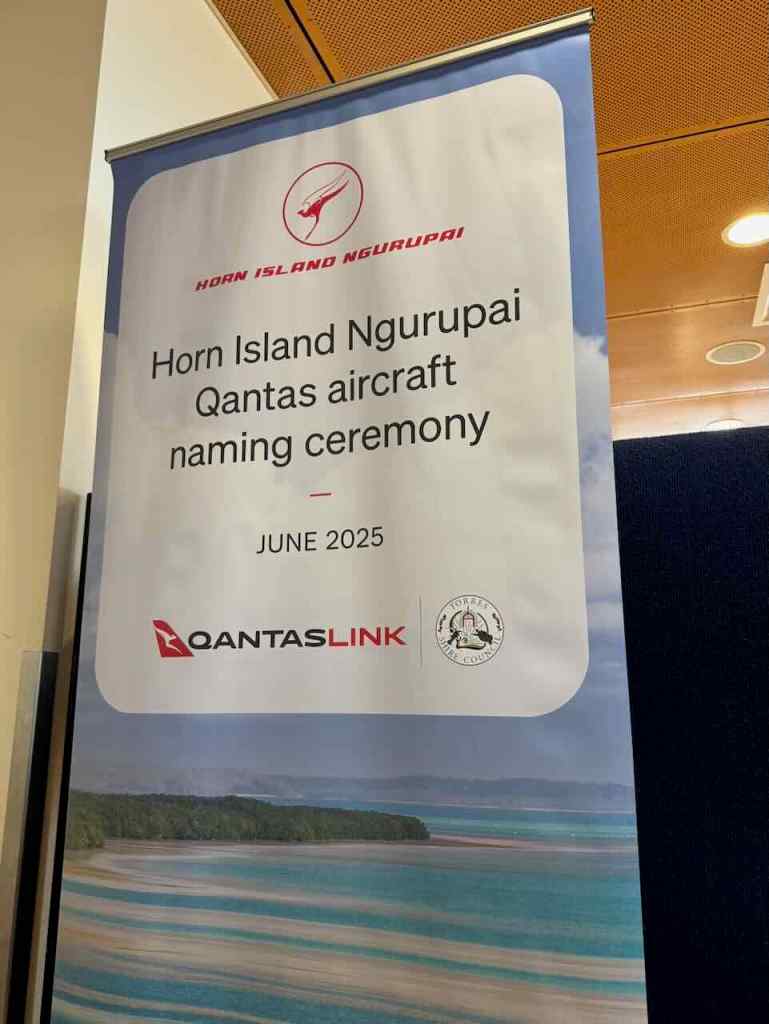

This issue of names and naming – of people and places – of course comes up in First Nations politics. I was interested that in Cape York there was far less use of local names for places (towns, rivers, and so on) than I expected. I asked Tom about it, and he simply said that it was coming. Interestingly, the week we were up there, Qantas had announced that it had renamed one of its Dash-8 aeroplanes, “Horn Island Ngurupai”. According to the National Indigenous Times this was done at the request of the Torres Shire Council. It seems rather little to me, but the Torres Shire Council chief executive Dalassia Yorkston is quoted in the article as saying that

“Even though our request was a simple one, it was a powerful one,” she continued. “Because it showed that beyond Horn Island we not only recognise that English name but we recognise the Kaurareg people, the Kaurareg nation, the traditional name.”

Back in 2012, I wrote a Monday Musings on the importance of place and researching local names in Noongar/Nyungar culture

Of course, naming frequently appears in First Nations writing. One example I’ve shared in this blog was in the opening paragraph of Ambelin Kwaymullina’s short story, “Fifteen days on Mars”, when our first person narrator says, pointedly,

It had been almost a year since we came to Mars. That was what I called this place although it had another name. It was Kensington Park or Windsor Estate or something like that but I couldn’t have said what because I could never remember it.

I love the way she turns this white-person excuse of “not remembering” unfamiliar names on its head.

Many First Nations novelists have used names to make political points. The names for people and places in Alexis Wright’s Carpentaria is another good example of using satire to make a point, with the town of Desperance and characters like “Normal Phantom” and “Mozzie Fishman”.

One of the issues that confronts non-Indigenous people is how (and whether) to write about Indigenous Peoples. I found a useful guide by Macquarie University, published in 2021, on “writing and speaking about Indigenous People in Australia”. It’s written primarily for those writing academic papers, and it recognises that language changes, but looks to be still relevant now and is worth checking out for anyone who is interested in their own writing practice.

I know I’ve just touched several surfaces in this post, but I wanted to capture some ideas while I could. I can always build on them later.

Thoughts or examples, anyone?

I always appreciate it when someone asks how to pronounce my name because so many people jump in and mangle it (it’s just a French spelling of one of the most common names in English–Jean/John) but you wouldn’t believe the variations I get on Jeanine. I do sometime feel that the mangling is an implicit criticism of me having a “difficult” name…and my name was chosen by someone else, so if there’s any difficulty, it’s not of my making.

I must admit Jeanne that I have wondered about the pronunciation of your name. In my head I’ve been pronouncing it the French way (as best as I can speak my schoolgirl French that is!) I’m sorry if people are critical of your name (given you didn’t choose as you say). For me, I would just be unsure how to pronounce it, and I’m pretty sure I’d ask you? The think I most hate is when I do this, I really can’t get the pronunciation because the language and its intonations are unusual to me. It really distresses me, because I want to get people’s names right.

I enjoy hearing it pronounced the French way but since I’m American I usually expect to hear it as we say the name of the pants–jeen.

I understand. Our son and partner liked the Irish name Niamh for their daughter, but they are spelt it phonetically as Neve, so there would be no confusion and she would be forever explaining herself. The joke is that when I do voice-to-text, the translation software nearly always writes it as Niamh! You can’t win!

Knowing how close to your heart is this topic – well, the wider version – I can well understand your finding relevance in the book.

Thanks MR … it’s interesting how different experiences align sometimes, isn’t it?

I agree with your thoughts. Names are used in a variety of ways especially those of us with a longer name. I go by Pam but whenever someone is stern with me I turn into Pamela. If it;s really bad my middle name gets thrown in. I also think the Australian language with the addition of all the ie or y endings on every other word gets thrown into the language too. We take a sickie, go to breky and on it goes. I’m surprised the photo was taken of Tom up close without his permission. That would bother me more than calling the man Tommy.. I don’t know, such an interesting conversation can be had around names.

Thanks Pam, I’m enjoying all these thoughts and perspectives, and yes re the Aussie abbreviations. I didn’t realised how much I used them myself until I started writing regularly to my American friend. It’s interesting how organisations like The Salvation Army and St Vincent de Paul’s have pretty much formally adopted Salvos and Vinnies now, haven’t they?

But that photograph situation was shocking to me. It’s probably something he has experienced a lot. It must take a hugely generous spirit to continue on…wanting to share their culture with us.

Totally agree about changing someone’s name – it is not okay. I figure they introduce with the name they want to be known as!

Thanks for the link to the writing guide – a useful reference.

That’s what I figure too … Kate. And, I’m glad you like the link. I was pleased to find it and thought it was worth sharing.

I’m not for a moment comparing my naming issues to First Nations battle for even tiny acts of correct naming. But: whenever a cafe worker or receptionist asks how to spell my name, or indeed spells it correctly, I thank them for the courtesy. Some acquaintances shorten it to John, which I hear as part of Australian culture where a full name registers as formal and distant. Because of peculiarities of my history, I feel it the other way: to call me ‘John’ is to fit me into your mold; ‘Jonathan’ is what my friends call me, and respects who I actually am. Yet there a handful of friends call me Jonny-boy, Jonno or other variations that I accept in the spirit in which they’re offered.

Thanks for these insights Jonathan. I try to listen to how people introduce themselves and use that from then on, but I think some Australians do just assume the diminutive form without thinking. And then, there are people who use some other form of your name as your relationship develops, like you Jonno, etc, and I think that’s to be treasured really (or, as you say, to be accepted in the spirit in which they are offered). It’s a complex business. But what these men did – in whatever spirit they did it – was culturally blind. In a situation like that you definitely do not use a diminutive or familiar form do you.

You’re completely right.

Thanks Jonathan!

A farmer I was working for when I was 18 was called Jack – and isn’t interesting that bosses are almost always not ‘Mr’ – and I just once called him John and he went right off. He was christened Jack and Jack was what he would be called.

I dislike the practice of giving migrants ‘English’ names, though you can hardly blame the migrants for going along with it, but my pet hate is men who accept nicknames like Boof (Boofhead) and Whacker. I just can’t bring myself to use them.

Oh yes, Bill, I have come across a few Jacks who are Jack (including my uncle. I have no idea whether people assumed he was a John. His name was Norman Jack, always known as Jack, because his father was William Norman, always known as Norman or Norm).

I agree re migrants, but I have also noticed that come do it themselves – some I suspect to fit in, and some because we can’t cope! Perhaps some of them prefer to have a name others can say rather than spend their lives having their name pronounced incorrectly (sometimes in a way that might even mean something else without our realising it. The tiniest change in intonation that we don’t hear can change the meaning of a being word, for example, to something unpleasant or insulting or just wrong.)

I love that you can’t use those derogatory nicknames, though I suspect some of them are intended affectionately or ironically (as in the boofhead is the exact opposite?)

When meeting new people my James will introduce himself as James and, usually older men, will immediately call him Jim. He will correct them and they will ignore him. So frustrating.

Naming is incredibly important. Some place names around the Twin Cities are being changed back to their original Dakota names and oh, has there ever been push back about it from a certain segment of people! But I think most people, when they learn about the whys, are understanding and supportive of the change.

My Mum would get that a bit too Stefanie … she was Jessie and people would often call her Jess which she hated and would correct them. I’m different … people can call me Susan, Sue, Susie, Sooz, whatever. But some with my name care a great deal about which version of the name they are or want to be called.

Reverting to original names is happening quite a bit in Australia too … and I’m sure with different levels of acceptance depending on the location and situation. Our national broadcaster is making a practice of identifying the “country” (Aboriginal country) they are broadcasting from. It’s a powerful way of ingraining it into our consciousnesses – the foodie names and/or the fact that there was an original name.

Strangely people always ask me what I want to be called and I reply that I don’t mind Stef or even Stefie, but they never ask how to correctly spell my name and will happily do it incorrectly even after I tell them “f” not “ph.” 😀

I’m really glad about the trend in reverting to original names. A few years ago the name of a large and popular lake was changed from the name of Calhoun, a racist slave-holder, back to Bde Maka Ska. There was huge support for the change and a beautiful piece of artwork by a native artist was installed by the lake with signage to provide information and context. Sadly, the historical society renaming a fort that sits on stolen land and where there was a mass hanging, did not go as well. Nonetheless, I think more and more people want to do the right thing which is heartening.

Names! There’s nearly always a catch! Your “f” is imprinted on my brain. About the time I “met” you I “met” a “ph” Stephanie blogger. It made it really easy for me to differentiate you both.

Thanks for sharing art Calhoun story. This is happening in Australian too as I’ve said – but in fits and starts. Support – or not – can be driven by local politics can’t it.

Such an interesting post, Sue!

As a Kim and NOT a Kimberley (I don’t even have a middle name), everyone likes to make my name longer, so I get Kimbo, Kimmy, Kimster etc. I answer to all of them and honestly don’t care. My sister, however, had a longer name that everyone shortens without her approval! The only person who can call her by her diminutive is immediate family. She gets very cross otherwise.

As a journo, I was always taught to ask people how they wish to be referred — and I tend to use that “rule” when I meet new people.

Anglicising names is a case in point. I was quite surprised by the Guardian reporting on the arrest of Liam Óg Ó hAnnaidh, from the Irish language hip hop group Kneecap (who I love), and choosing to use an anglicised version of his name (which he does not use). I thought this was rude and almost an act of political oppression. I wouldn’t have been surprised if the BBC reported it that way, but expect better of the Guardian. (BTW, the BBC always use his Irish language name.)

Thanks Kimbofo (see, I use that because it’s your wordpress moniker and the way I first met you), I know a Sue who is a Sue and has no middle name. Although I’m a Susan with middle names, she and I have a little in-joke where we refer to each other by our Sue plus last names, hyphenated when we write it. Like you I don’t care what people call me. Our grandchildren have single syllable names, and in the family we tend to lengthen them exactly the way people do yours. Our son and daughter have two-syllable names that have no common shortenings and in the family we often lengthen those too.

Your journo rule, is the one I go by when I am introduced people. It seems the right thing to do. That’s an interesting and disappointing story re The Guardian. A lack of subeditor doing the check do you think?

(PS I hope you don’t mind the kimbofo! There are a couple of bloggers who call me Gummie. I like it as it feels friendly.)

The first thing I thought of was the Gulf of Mexico being renamed the Gulf of America. What a silly pissing contest that is, though, if we use all of our best brain cells, we can agree that both the U.S. and Mexico are in North America. However, I am aware that when the president and his friends say “America,” they mean U.S., hence my comment about the pissing contest.

Connected naming to your recent novel, James, slaves’ last names were changed based on who owned them, thus stripping them of their own lineage in connection with names. Then, you get Malcolm X and other Nation of Islam people who replaced their last names with X because last names derived from a history of slavery (Malcolm’s last name was originally Little, meaning somewhere in the past, a white person named Little owned Malcolm’s ancestors). The X functions as a placeholder for when they learn their true identities and histories.

Oh yes, the Gulf of America! Good catch Melanie in terms of our discussion. I sometimes use America for the US, but mostly I try to say the US or USA, but if I use the adjective American, I do mean those from the USA because otherwise we have Canadian, Mexican etc. It’s complicated for the US I think.

And thanks for reminding us of the whole Malcolm X issue.

It’s such a rich topic. A Canadian novel I recently finished is titled with the Czech word for love, but it’s left vague, so that you can’t really tell whether it’s named for the emotion or for a pet name that one would call their significant other. And in the story, it’s clear that the narrator has fallen so hard for her boyfriend that she can’t tell where things begin or end either, and forgets so many other aspects of her identity while she follows his every move around the globe, all that she knows is how much she is in love…to the point where it feels like that actually IS her name.

As another tangent, Thomas King’s mystery series was, in the beginning, published under the name Hartley Goodweather, featuring his protagonist Thumps Dreadfulwater: it was quite the mystery at the time (and a delightful send-up) with even his author photo taken under the shadow of a hat-brim but, since, those early mysteries have been republished under his proper name (as a Cherokee-Greek writer, which you know, having enjoyed his Borders so much).

Thanks Marcie for both these stories.

I didn’t know that about Thomas King. It’s interesting when authors do this. There are so many different reasons for doing it too – to hide gender, to hide race/ethnicity/to separate out different genres of writing, etc. I love Thumps Dreadfulwater!

Various thoughts:

My surname, a not uncommon patronymic, is spelled variously across national borders in Europe. At least one of my teachers in high school adopted the wrong one, and never addressed me otherwise.

Quite a while ago, NYRB Classics brought back into print Names on the Land by George Stewart, about American place names. Once on a boring trip, I tried the exercise of sorting American state names into those of European origin and those of local origin. The latter are in a majority. The tricky part of the exercise is ordering your states as you go to keep from forgetting one or two. (I go north to south, then east to west.)

Those who have read Flann O’Brien’s The Poor Mouth will surely remember “Yer name is Jams O’Donnell”, as the Irish children acquire standard names at the schoolhouse.

Philosophers argue about names. Saul Kripke wrote Naming and Necessity to take on Frege’s and Russell’s theory of definite descriptions. Later on, in Whose Justice? Which Rationality, Alasdair MacIntyre offered arguments against Kripke’s arguments.

Thanks George. I am enjoying the variety of thoughts this post has generated. I don’t know that Flann O’Brien work, but how many education systems did things like this!

I guess I’m not surprised that philosophers have discussed the issue, nor that their thoughts and opinions vary. I don’t know Kripke at all.

I use “U S of A” in all writings and conversation.

Sounds eminently sensible fourtriplezed.

Fascinating discussion Sue. I think names are important, but Australians do like to add ‘o’, ‘ie’, ‘ster’ etc to names as a sign of affection/belonging usually, so I can kind of understand how that happened on your trip. But taking someone’s picture up close without asking and/or having a conversation first astounds me!

I accept all versions of my name except for Bronnie/Bronny. I had a teacher who called me that in 4th grade and I hated it with a passion. It has turned out well as Mr Books also has a cousin called Bronwyn and she is happy to be Bronny, while I get Bron, Brona, Bronsie and even for one brief period of my life The Bronster!

Thanks Brona … yes I can understand it too but it just felt blind at best and so very wrong at worst.

I love the Bronster. Mr Gums’ mother was Mickey to her daughter – nothing like her real name of Dorothy – so became Grandma Mickey. Our son created a cartoon superhero type figure for her called The Mickster.

That’s so lovely, seeing your grandmother as a superhero.

We’ve been wondering what grandparent names will come our way eventually – at the moment I’m pushing for Nonna Brona 😀

I love Nonna Bronna! Rhyming (or even rhythmical) names are so joyful.