I said in last week’s Monday Musing, which was dedicated to (Kaggsy’s Bookish Rambling) and Simon’s (Stuck in a Book) 1952 “Year Club”, that I wouldn’t write about the ongoing issue of journalists and academics feeling the need to defend Australian literature, because I’ve discussed it before. However, I did read an interesting article on the wider issue that I thought worth sharing. Yes, I know the week officially ended yesterday, 27 April!

Bartlett on Aussie culture

The article I’m talking about came from someone called Norman Bartlett. Born in England in 1908, he migrated to Western Australia with his parents in 1911, so he grew up Australian (albeit he did live in England again with his mother and sister between 1919 and 1924). According to the NLA’s Finding Aid for his papers, he studied journalism, obtained an Arts degree, and served with the RAAF in World War 2. In 1952, he was literary editor and leader writer for Sydney Daily Telegraph and Sunday Telegraph. The article in question was written in reflection of the 1951 Golden Jubilee of the Commonwealth of Australia.

Titled “Let’s take stock of Australian culture”, it appeared in the Daily Telegraph (5 January). Bartlett’s fundamental question was whether Australia had “grown up as a nation”. This meant, he argued, much more than things like “Dominion status, industrial development, the fighting reputation of the A.I.F., a record wool cheque, and prowess at tennis, cricket, and, with reservations, Rugby, football”. Yes, indeed! Rather, it means

maturity in art and literature; a distinct and original “way of life”; a quickened awareness of what being an Australian means; and why being an Australian is different from being an Englishman, an American, or a European.

A national culture is much more than a cultivated minority’s appreciation of good books, pictures, music, and architecture.

It is the way we — the majority — feel, think, act, talk, wear our clothes, play our games, and fight our wars.

When our literature, art, music, architecture, and philosophy reflect our national idioms and attitudes they become part of our national culture. Thus, a truly national culture is the expression of a particular people living in a particular place for a long time.

Of course, he doesn’t consider the nation’s original inhabitants in any of this, particularly when he says “originally, Australians were colonials. That is, slips from older stock transplanted into an initially alien soil”. I will just leave that thought, because we are talking 1952 and I think the best thing for us to do is to recognise this context in all he says.

His article aimed to analyse “whether we’ve taken root; whether we are making a collective, intelligent attempt to adjust ourselves to our environment; whether our environment reflects itself in our speech, attitudes, art, music, and literature”. He argues that by the late 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries, writers and artists were moving away from “writing and painting in the English style”. They were “beginning to wake up to the fact that Australians had grown different from the parent British stem”. Not only were writers like Henry Lawson, Joseph Furphy (“Tom Collins”), “Banjo” Paterson, A. H. Davis (“Steele Rudd”) expressing this difference in their stories and verse, but they were writing in “everyday idioms of the Australian people”, as Mark Twain had done in America.

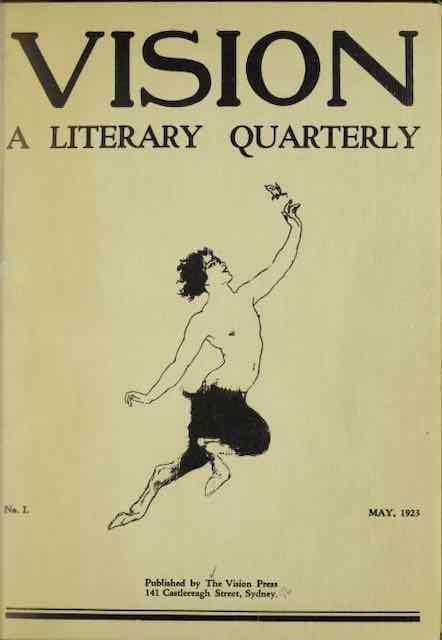

He quotes American critic, C. Hartley Grattan, who argued that a fundamental characteristic of ‘this budding Australian literature was an “aggressive insistence on the worth and unique importance of the common man”.’ But, Bartlett says, with “the growth of a more sophisticated city life, many writers began to feel that aggressive semi-socialistic nationalism [as seen in many of the above-named writers] wasn’t enough”. Writers and artists like the Lindsays and Kenneth Slessor wanted to “liberate the Australian imagination from droughts, gum trees, drovers, and the wide-open spaces”. In 1923, they created a literary magazine called Vision, but soon, says Bartlett, the Lindsays’ romanticism, with its “bookish carnivalia rosy with the fumes of canary wine and cheerful with the seductions of full-breasted wantons … blunted itself on Australian realism”. Love this!

By the Jubilee, increasingly more Australian writers were “realising that life is where you look for it”. He said writers like Kylie Tennant, Frank Dalby Davison, and Xavier Herbert showed there was ‘still plenty of kick in the Australian “bush” tradition”‘ while those like Ruth Park, Dymphna Cusack, M. Barnard Eldershaw, and Dal Stivens, were “more interested in the cities”. He separates out Eleanor Dark, who, despite setting some of her novels in country towns, had “a sophisticated interest in character rather than place”. Overall, he argued, that Australia’s contemporary fiction writers were “more analytical than exultant about the Australian way of life”.

Bartlett also wrote about poetry, visual arts, music and, briefly, dance. You can read these thoughts at the link provided above. He concludes by stating that “Australians are a reading people”, who spent significantly more on books than Americans and Canadians. This rather quantitative conclusion doesn’t answer much in terms of his framing question. However, I liked his discussion of how the bush and city strands were playing out in mid-20th century Australian literature, and his assessment of contemporary writers being more “analytical than exultant” is what I’d like from our artists of all persuasions. What do you think?

Very interesting bloke; very interesting thoughts !

Canary wine ?

The quote “more analytical than exultant about the Australian way of life” is, I think, absolutely spot on: it’s who we are.

I thought so too, MR, and well expressed aren’t they.

Canary Wine was/is a sweet wine from the Canary Islands but I think it might also have been a generic term for sweet fortified wines.

You mean there were once people who drank stuff like Brandivino on purpose ??

Canary wines were fortified white wines from the Canary Islands, popular in England during the 16th and 17th centuries, and much favoured by royalty and the upper classes.

Learning something new every day is what I like ! 🙂

Haha … sounds like.

Interesting reflections. How a notion i forged and grows its roots. And i was reminded of those Australians whol eft and re-invorated the ‘mother’ country – the Germaine Greer and Clive James generation.

And then not judging the past – in this case 1952 – through our own equally distorted lenses .

I don’t know the answer to these questions and don’t know enough to even hazard an intelligent view: Is Australia coming into carving its own distinctive self? Or has it lost its way and must regain its footing. I see Australians batting this back and forth all the time on various platforms.

I think you have a point Josie – though I feel, and hope, it’s two steps forward and one step back. I think we have become more confident in out own culture, but as culture keeps changing and as the world keeps changing, then I think so does our confidence. We are always anxious bout the influence of “bigger” cultures on us, aren’t we.

And yes, good point re Greer, James and co, though I think they departed in the 60s?

Hi Sue, I don’t know the answer, but I think after the war Australians became more confident in themselves and Australia. Yet, as the same time I think authors had to travel overseas to be recognised and published. Australia also became more urbanised in the 50’s. The economy grew; manufacturing grew and offered jobs in the cities. And, stories grew not only from the rural areas, but also now more from the cities. Thus, as Australia took on its own identity from the mother country, Australian authors were probably more analytical and exultant in their writings.

Thanks Meg … these are good thoughts. It’s fascinating to think about isn’t it?

I always think of Australians as laid back, rugged, and independent. As a people, you seem more “character driven” than plot driven. I can’t imagine asking an Aussie, “where do you see yourself in five years,” because that would miss the point of being alive and whether your mate “Tits McGee,” or whatever, will come round and help you get that alligator out of your back yard, cuz the bastard is back again.

Haha Melanie, I love your characterisation of us … and there could be some truth in that character versus plot driven idea. Our mantra is not, I guess, you can be what you want to be so now go get it.

Such an interesting read, particularly the thoughts on what constitutes national culture! I hadn’t come across Bartlett before, so thank you for the introduction.

Thanks very much Jacqui. It was that in particular – his ideas about national culture – that made me write this post.

It’s hard not to go down the “defense of” Australian/Canadian lit though, isn’t it. Such a cornerstone of literary “identity”. I think, too, of Margaret Atwood’s Surfacing (1972), about relationships and wilderness, but also about differences between America and Canada and how perspectives and worldviews vary/contrast. and whether/how Canadian novelists told a different kind of story (from England, from other colonial countries). I think it’s interesting that anyone would simply remove a writer from the urbanVrural divide because they were actually more character-driven novels (Dark’s) and I wonder whether someone who’s read more Dark than I have (probably most people, as I’ve only read The Little Company!) would think that’s a valid distinction.

It is… I must read Surfacing! It’s such an interesting challenge to identify the essence of that different kind of story – something Bill in particular talks about a lot, the influences that can drive it (such as the bush influence here, and myths about what “the bush” meant). As for Dark, yes, very good question Marcie. I did think that distinction was a little curious, and a bit stronger than is probably valid, but I haven’t read enough of those contemporary bush writers to argue the case.