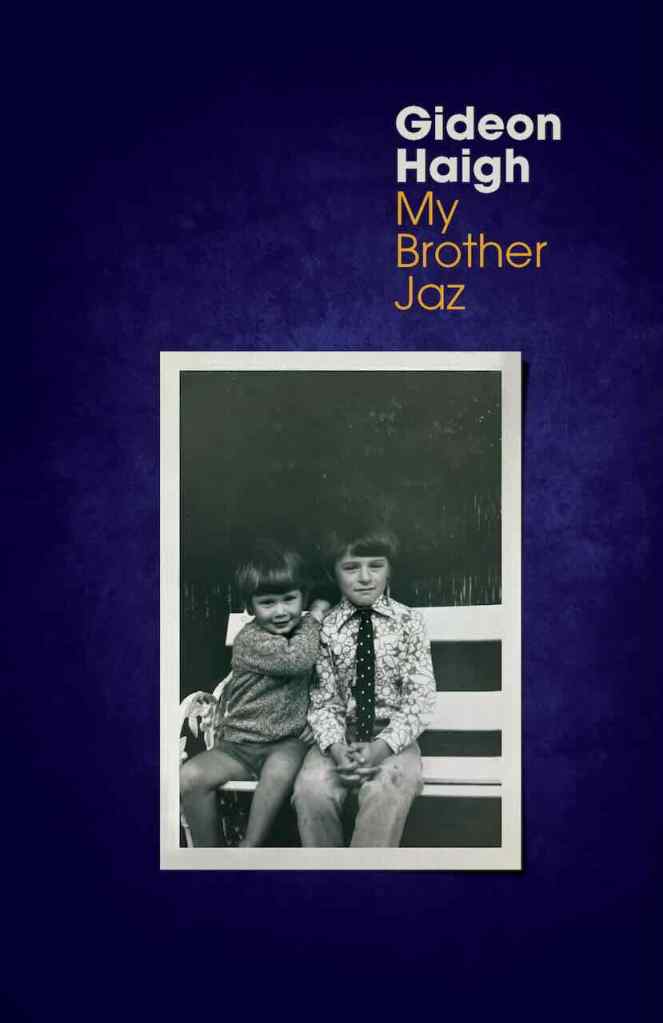

When I posted my first review of the year – for Marion Halligan’s Words for Lucy – I apologised for starting the year with a book about grief and loss. What I didn’t admit then was that my next review would also be for a work about grief and loss, Gideon Haigh’s extended essay, My brother Jaz. This does not herald a change in direction for me, but is just one of those little readerly coincidences – and anyhow, they are quite different books.

For a start, as is obvious from its title, Haigh’s book is about a sibling, not a child. It was also much longer in the making. Halligan’s book was published 18 years after her daughter’s death, and was something she’d been writing in some way or other all along. Words are also Haigh’s business, but he ran as far as he could from his grief, and it was only in 2024, nearly 37 years after his 17-year-old brother’s death, that Haigh finally wrote, as he says in his Afterword, “something I had always wanted to write, but had suspected I never would”.

Before I continue, I should introduce Haigh for those of you who don’t know him. Haigh (b. 1965) is an award-winning Australian journalist, best known for his sports (particularly, cricket) journalism, but also for his writing about business and a wide range of social and political issues. He has published over 50 books. I’ve not read any, but I am particularly attracted to The office: A hardworking history, which won the Douglas Stewart Nonfiction Prize in 2013. However, I digress …

Unlike Halligan who, to use modern parlance, leant into her grief in what I see as a self-healing way – as much as you can heal – Haigh did the opposite. He did everything he could to avoid it; he worked, he writes, “to flatten it into something I could roll over”. And it affected him. If he, just 21 at the time, was a workaholic then, he doubled down afterwards and work became his refuge, his life:

It was the part of me that was good; it was the only part of me I could live with, and that sense has quietly, naggingly persisted. Go on, read me; it’s all I have to offer. The rest you wouldn’t like. Trust me. You don’t want to find out.

If this sounds a bit self-pitying, don’t fear, that is not the tone of the book. It is simply a statement of fact, and is not wallowed in. It represents, however, a big turnaround from someone who admits early in the book that he was known for his “pronounced, and frankly unreasonable, aversion to autobiographical writing”. This aversion was despite the fact that, “at the same time, trauma, individual and intergenerational” was something he’d written about – and been moved by – for a long time. So, in this first part of his six-part essay, we meet someone who had experienced deep pain, but had shrunk from indulging in a certain “kind of confessional nonsense”, and yet who increasingly found himself “backing towards an effort to discharge this story” to see if it made him “feel differently”.

What changed? Time of course is part of it. Haigh shies from cliches, as he should, but grief will out. It just can’t be bottled up forever, no matter how hard he tried, and so in early 2024, during the Sydney Test Match no less, “something previously tight had loosened” and over 72 hours he wrote the bulk of this essay. A major impetus was the break up of a relationship. It was time for a “reckoning”, he writes on page 76, but much earlier, on page 47, he alludes to it:

Why did I even start this? The only reason I can think of is that it has to be done. It can’t remain unwritten, just as I could never leave Jaz unremembered. I have myself to change, and how am I to do this unless I examine this defining event in my life face on?

This idea of the examined life is something Halligan mentions too in her memoir. She writes near the end of her book that “I do believe that the unexamined life is not worth living, and that an enormous part of that is the recollected life”.

What I hope I’ve conveyed here is the way this essay is driven – underpinned – by a self-questioning tone, more than a self-absorbed one. Even as Haigh writes it, he is interrogating his reasons (and perhaps by extension anyone’s reasons) for writing about the self. That this is so is made evident by the way the narrative, though loosely chronological, is structured by the writing process rather than by the “story”:

“OK it’s getting on to dawn, and I’m going to click on ‘Jasper Haigh [inquest] Reports for the first time” (p. 29)

“It’s raining, but I’ve just returned from a walk. I often walk when I have something to turn over in my head.” (p. 33)

“I’m at the point right now where I just wonder what the hell I am doing.” (p. 47)

“I have picked this up again after putting it aside to draw breath, to consider what next … So, I’m going to stagger on, with the excuse that this is no memoir: this is less a geology of my life than a core sample.” (p. 61)

This approach helps us engage with a writer who prefers to push us away. It finds, in a way, the art in the artifice, and enables Haigh to write something that questions the memoir form while at the same time paying the respect that the best memoirs deserve. It’s a juggling act, and I think he pulls it off.

By the end, Haigh is not sure whether writing this work – this raw “reckoning” to re-find his emotional bearings – has achieved anything. It is, he believes, “too early to tell”, but I wouldn’t be so sure. He is a writer, and he has put on paper the defining event – the “core sample” – of his life. That has to mean something.

Gideon Haigh

My brother Jaz

Carlton: Melbourne University Press, 2024

87pp.

ISBN: 9780522880830

It’s interesting that this review is about the writer rather than about the book’s content.

Yes, I know what you’ve used is from the book … but I don’t resile from my comment.

Fair comment MR … but I don’t resile from writing about what interested me! And, in fact, in many ways the book’s content is the writer – his thoughts about what he was doing and why, with the why being very largely to do with him. I’ll be interested to see what others who have read it say.

We do hear about Jaz, but unlike your Stringer who had many decades of life, Jaz had less than two. The hole he left is huge but his life itself was short.

(Hmmm I hate labouring the obvious but perhaps sometimes I assume things are obvious that in fact aren’t?! You keep me on my toes!)

Oh darlin, it was not meant as a criticism, but a genuinely interested comment. (And I used to love Gideon’s cricket commentaries.)

Haha thanks, MR. I didn’t take it as intentionally negative, but it was an interesting observation that made me think. I love the way you “read” my reviews. Don’t ever stop commenting on how they come across to you.

I read this one just before Christmas. And I agree with MR’s comment (and your blog comments) that the book is definitely about the effect of Jaz’s death on Gideon, and less about Jaz himself. You’ve covered most of the aspects of the narrative that I found most poignant, but I was almost more sad at the loss of romantic partnership that helped bring the book into being. Maybe that’s me being inappropriately sentimental, but it’s clear that the avoidance of grief has taken a significant toll, and that Haigh is finally clear-sighted enough, and honest enough, to recognise this.

You might want to take a break from reviewing “grief memoirs” (for lack of a better abbreviation) for a while. But I made a deliberate point of reading this book before tackling Dani Netherclift’s “Vessels”, which covers similar territory but much more in the mode of a lyric essay. I would be really interested to see how you think the two approaches compare with one another. And meanwhile, I think I should dig out Marion Halligan’s book and continue my own comparisons.

Oops…WordPress doing tricksy things to me again…sorry.

That’s ok … I’ll delete the duplicate one!

Thanks Glen … well said. I should perhaps have been more explicit about the loss of his relationship with ”D” being the trigger for him finally realising he needed to do something about himself and recognising that his grief was a – the – “core” issue.

I haven’t heard of Dani Netherclift but I will make a note. I’ll be interested in your thoughts on the Halligan if you read it.

It’s Dani’s debut as a standalone book author, and definitely deserves a strong readership. Here’s a link for you and your other readers:

https://upswellpublishing.com/product/vessel

Oh, Upswell! I have a few of their books, and have preordered a couple this year. But then I need to find time to read them. Will note that one.

Ahh ! This reminds me strongly of “Frequency”, a movie I’ve loved since first seeing it. It’s based on a young man’s unexplored grief for the loss of his father, and how that affects everything he does. In fact it’s a feelgood movie in the long run, starring Dennis Quaid (still young and yummy – it was made yonks ago) and Jim Caviezel, excellently cast because he radiates sadness all the time !

Sorry …? Oh, off-topic ? Surely I never go off-topic, ST !!!!!

Not completely off topic MR!! You always have some link and I reckon grief is a fair enough one here. And, I never reject a good movie recommendation. I haven’t heard of this one.

It’s a murder mystery set in a science fiction b.g., and contemporary. [grin] Sounds horrible, I know; but it totally holds you and you end up thinking how wonderful it would be if …

Sounds intriguing … not sure whether it would be for me or not.

I doubt it …

Haha … I think you know me so I’ll take that as advice…

I spotted this slim volume at work and wondered about it, but as you can imagine, I have that feeling almost every hour when at work 😀

If I acted on it each time my library would be even more out of control than it is now. So for now, thank you for you reading these books that I hope to get to one day, and for reviewing them so gently and thoughtfully.

I can understand of course. This was one of those buys at the NLA Bookshop. I rarely do it but the Haigh name, my own experience of losing a sibling relatively young (though not as young as Jaz), and the fact that it was short got me over the line. If any one of those three had been different I doubt I would have bought it. (Unless the Haigh name were replaced by some other writer I hadn’t read and thought worth trying!)

I’m glad you got something out of my posts on these two books.

Always – I just don’t always have the time or the ability to think of anything worthwhile to comment on every post – but I do enjoy the different ways you consider the books you read.

I completely understand … and I have taken more, in recent times, to visiting my favourite blogs in little bursts, because I can’t keep up on a day to day basis.

Ha, that’s exactly what I’ve been doing today 🙂

I rather noticed… haha!

It’s really hard to sit with challenging feelings and accept that they are happening to you without wanting to do anything to ignore or cover them up. On top of that, I can’t imagine it being one of the hardest feelings ever, stemming from the death of a loved one. I’m only somewhat recently learning how to sit with emotions and not do something. I’ve always done something. That’s anxiety.

Thanks Melanie … there’s a real challenge I think in working out which emotions should be sat with and which ones need attention? I think sitting for a little while at least is the best start … and then you can assess whether that’s all you need to do or whether you really do need to act in some way? Does that make sense?

Yes, I think the point to sitting with the emotion is not to do something unhelpful, like stress, panic, drink, use drugs, eat, etc. The problem isn’t the same things as the emotion, so yes, once you’ve sat with the emotion, then you can attack the problem.

Thanks for confirming that Melanie …. That’s sort of what I guessed must be the case.

I enjoyed Gideon Haigh’s cricket writing, though Peter Roebuck was my favourite. I certainly believe that trauma must be talked (or written) through, but I don’t think I would read such an account without trauma of my own to compare it to.

Thanks Bill … I think you are right that these sorts of books mean the most to those who have experienced something similar, though I can sometimes be tempted if the person who has experienced the trauma interests me for some reason.

Cricket lover all my life and can hardly read it at all now. It just seems the same old chat. Mind you that may describe any sports reading for me so far unless it is social history. Never knew Gideon Haigh did anything other than cricket.

Thanks fourtriplezed. Agree re social history and sport … sport is a big thing and worth reading about in terms of its role and context isn’t it.

As for Haigh, I think it was that office book that brought him to my attention as not only a cricket expert!

Sneaky of you, to not suggest that you’d have another on the same theme, coming on the heels of the first. But it makes sense to read them in company, too. It’s not always true, I don’t think, that one wants to read on this theme because one has loved and lost; I used to read a lot on this theme when I was very young (and thought it the height of Romance and suffering and all that) but after I’d begun to have experiences of loss myself I more often steered clear. It could no longer be only someone else’s story after that.

Haha Marcie … I didn’t want to put people off my blog.

Interesting re your reaction. When my sister died in our thirties I was devastated and desperate to read other people’s experience, fiction or nonfiction, to help me work through it, to make sense, to find the like minds and the different minds, and there wasn’t much from a sibling POV. Still isn’t probably. It’s still mostly parent-child and spouse/partner stories that dominate this field I think, though I don’t actively seek these books out anymore so this is just my sense.

Aw, that makes sense. I have had that experience of desperately seeking an answer in books and not having been able to find anything which aligned with my experience; it feels doubly lonely, doesn’t it, because books have always been there for you but they don’t seem to contain THAT wisdom when you most need it.

Exactly!

I just read MBJ so glad to find these reflections. But Gideon was NOT born in 1959 – more like 1965/66.

Thanks Lizzie, and you are right. The date was linked to Haigh’s Wikipedia article, which indeed says 1965! Must have been a little conniption between brain and hands. It’s still linked to Wikipedia but on the right date.