While some of the forgotten writers I have shared in this series are in the category of interesting-to- know-about-but-not-necessarily-to-read, others probably are worth checking out again. Jessie Urquhart is one of these latter, though I’ve not read any of her novels, so don’t quote me!

However, there are articles for her in Wikipedia and the AustLit database, and I have mentioned her on my blog before, so this must all count for something in her favour. My reference was in a Monday Musings on Australian women writers of the 1930s in which I discussed an article by Zora Cross. She talked about, among other things, writers who had achieved success abroad without leaving home. One of those she named was Jessie Urquhart, who, she says, “will not, I think, do her best work until, like Alice Grant Rosman, she relinquishes journalism for fiction”. I commented at the time that this was interesting from someone who, herself, combined fiction and poetry writing with journalism. I also wondered whether Urquhart needed her journalistic work to survive. (I suspect she did.)

I also wrote earlier this year about Urquhart on the Australian Women Writers (AWW) blog, as did Elizabeth Lhuede last year. This post draws from both posts and a little extra research. In my post, I shared a 1924-published short story titled “The waiting”. It is an urban story about a very patient woman. It’s not a new story, but Urquhart writes it well. … check it out at AWW. You might also like to read the story Elizabeth posted, “Hodden Grey”, which is a rural story. Like many writers of her time, Urquhart turned her head to many ideas and forms.

Jessie Urquhart

Novelist, short story writer and journalist Jessie Urquhart (1890-1948) was born in Sydney in 1890, the younger daughter of William and Elizabeth Barsby Urquhart. Her father, who was a Comptroller-General of NSW prisons, had emigrated from Scotland in 1884. She joined the Society of Women Writers and was secretary for 1932-33. She had an older sister, Eliza (1885–1968) with whom she emigrated to England in 1934 (years after Zora Cross’s article!) There is much we don’t know about her life, though her father’s obituary does say that neither of the sisters married.

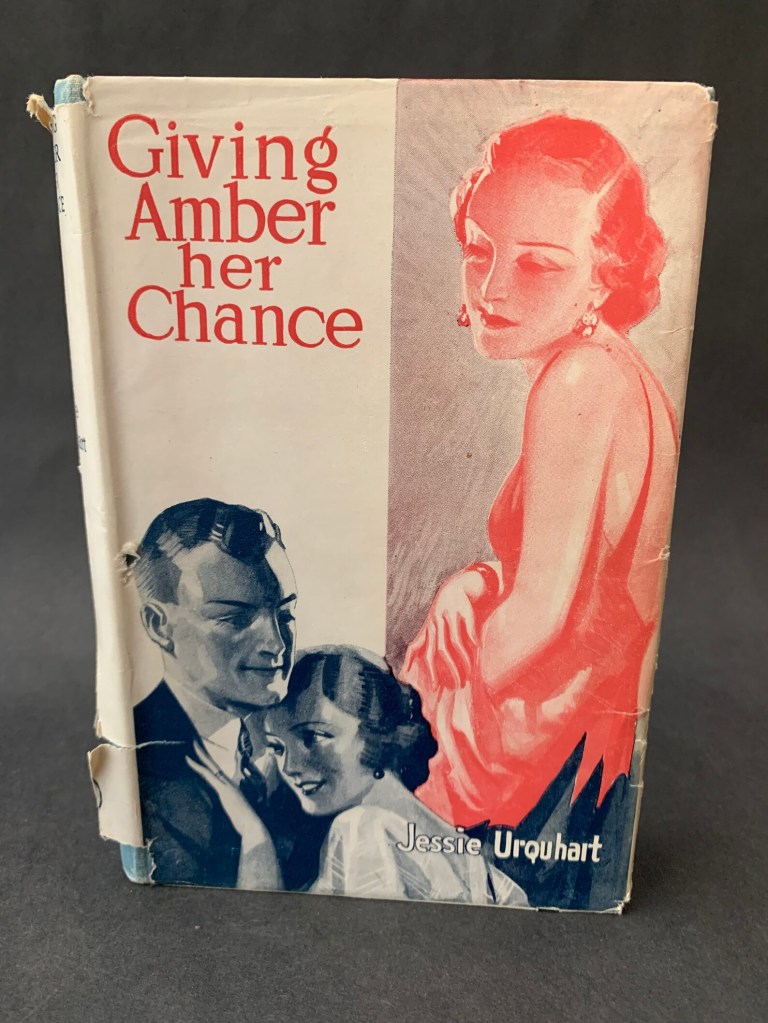

In an article titled “Women in the World” in 1932, The Australian Women’s Mirror includes a paragraph on Urquhart, because they were about the serialise her story Giving Amber her chance. They say she “started writing very young, and in her teens had a novel, Wayside, published; she is now a Sydney journalist. Short stories and articles from her pen have appeared in the Mirror, her latest contribution being “The Woman Prisoner” (W.M. 8/3/32), based on her knowledge of the Long Bay women’s reformatory.”

Elizabeth’s thorough research found that Urquhart had turned to short story writing and journalism, in the 1920s, with most work published in The Sydney Mail, but she was also published in The Sydney Morning Herald, The Australian Woman’s Mirror, The Australian Women’s Weekly, The Sun and Queensland Figaro. Elizabeth read (and enjoyed) many of her stories, and wrote that they cover “a broad range of settings and topics, giving glimpses into the lives of modern Australian urban and rural women and men, encompassing the adventures of spies, adulterers, thieves and deserters; the faithful and unfaithful alike”.

According to Elizabeth, Urquhart’s first publications actually appeared when she was in her twenties, including a series of sketches titled Gum leaves which was published in The Scottish Australasian. The Goulburn Penny Post quoted the paper’s editor, who said that:

The sketches represent her initial effort, and indicate that she has the gift of vivid description and the art of storytelling in a marked degree. All the delineations show power and a creative facility which promises well. Some are indeed gems. [The author shows] promise of a successful literary career.

Her novel Wayside appeared in 1919, and is probably based on these sketches. (She was not a teen in 1919, so I’m not sure about The Australian Women’s Mirror’s facts.)

Anyhow, according to Elizabeth, Urquhart had “a year’s study abroad” sometime in the late 1920s or early 1930s, and wrote more articles on her return. She lived in Bellevue Hill, Sydney, and continued to publish what Elizabeth nicely characterises as “her quirky short fiction”. She also wrote more novels. Giving Amber a chance, serialised in 1932 in The Australian women’s mirror, was published in book form in 1934. The Hebridean was serialised in 1933, but was not published in book form though, wrote Elizabeth, it was “arguably” the better novel. She liked “its setting and its depiction of class tensions” and believes – a propos my introduction to this post – that it deserves to be more widely read.

Another novel, Maryplace: the story of three women and three men, was published in 1934, but unlike the previous novels does not appear to have been serialised. Elizabeth found a contemporary review, which she liked for the sense it gives of the debates surrounding Australian writing at this time, including a reading public “mistrustful of its own novelists”. The author of the review writes that Maryplace is

a story which takes the art of the Australian novel to a new plane of modernity of treatment and universality of appeal.

In style, in theme, and in the power of characterisation and analysis this book is far above the work of the average of our novelists. It is deserving of the highest recommendation. Despite the fact that the scenes of Maryplace, with the exception of one period, are laid in a New South Wales country town, the story will be of equal interest to any reader of novels anywhere. That, after all, is the real art of the novel, and it is one which is not so frequently cultivated by our writers that we can afford to ignore it when we encounter it.

The reviewer believes there’s been too much self-conscious talk about “an Australian story-art”, that all literature is naturally a product of the country which produces it and the life and times in which it is produced. In other words, says R.N.C.,

All stories have their roots in the soil. They will be true of a nation and be part of a national contribution to art without ceaseless striving to label them and brand them as ‘Australian’ on every page and in every paragraph.

Urquhart’s story, R.N.C continues, has the “unselfconsciousness that gives her book a real Australian atmosphere and setting” but that also “makes it a story of absorbing human interest and power so as to be a world novel for the world”. (I like R.N.C.’s thinking.)

The novel apparently deals with the class tensions, and a changing order which sees “the local butcher or grocer” no longer willing to deliver their goods to “the back door”. This is part, says R.N.C. of “any fast changing democracy, and Miss Urquhart in her Maryplace has drawn it with pitiless detachment, giving to her theme sympathy and understanding but the touch of irony and satire which it demands”.

After she went to England in 1934, Urquhart’s stories continued to appear in the Australian press, but whether she published elsewhere is not clear. She was clearly still active in writing circles in 1941, because she was chosen as Australia’s delegate to the PEN conference in London. She and her sister survived bombing during the war, and Jessie sent regular reports about life in London to The Sydney Morning Herald.

In 1944, the Herald reported that “gossip of London theatres, the Boomerang Club, books and their authors comes from Miss Jessie Urquhart, formerly of Sydney, who went to England before the outbreak of war”. It says that “during the first great blitz, she was an A.R.P. telephone worker” but was now “a reader for Hutchinson’s Publishing firm”. She and Eliza had been “staying with novelist Henrietta Leslie in Hertfordshire for the past three months”. Wikipedia tells me that Leslie was a “British suffragette, writer and pacifist”, which makes sense when you read in the next sentence that Jessie had “just been re-elected to the committee of the Free Hungarian Club Committee” which was chaired by Hungarian writer and exile, Paul Tabori.

She is an interesting woman, and would surely be a great subject for one of Australia’s literary biographers!

Anyhow, in 1945, another Sydney Morning Herald paragraph advised that Jessie and Eliza Urquhart would “probably visit Australia” again in 1946, and that they had reported that London was “beginning to recapture its old smartness”. I suspect Jessie never did get back to Australia, as she died in a nursing home in St John’s Wood, London, in April 1948. Eliza died in 1972.

Sources

- Zora Cross, “Australian women who write: Many fine novelists and poets“, The Sydney Morning Herald (Women’s Supplement), 4 April 1925 [Accessed: 18 November 2024]

- R.N.C., “Australian woman’s powerful novel“, Sunday Mail (Qld), 30 December 1934 [Accessed: 18 November 2024]

- Social News and Events, (1944, November 1). The Sydney Morning Herald , 1 November 1944, p. 6. [Accesed: 18 November 2024]

- Social News and Events, The Sydney Morning Herald, 29 August 1945, p. 6. [Accessed: 18 November 2024]

- Jessie Urquhart, AustLit.

- Jessie Urquhart, Wikipedia [Accessed: 18 November 2024]

- “Women in the world”, The Australian Women’s Mirror, 5 April 1932 [Accessed 18 November 2024]

Neither of those two stories is exactly cheery … But they’re both absolutely readable.

I’m thrilled you read them MR. They show what a good writer she is don’t they… and that review of her novel is so interesting.

She did seem to have a mind in advance of her times, as it were. (Yeah, I could write that better, but it’s early, ST …)

And I understood your point and that’s rude important thing.

It seems like a particularly notable fact that she had a novel published when she was in her teens, with not only the question of being female but also her youth being potential “reasons” (as unreasonable as that is) to unfairly dismiss her wholesale back then.

It does Marcie … only trouble is, I’m not sure that she did publish it in her teens… as far as I can tell she was born in 1890 and it was published in 1919. If I can do my sums correctly that doesn’t make her a teen.

Still, regardless I think it was an achievement given those times.

I do not know the Urquharts at all, so loved this. Our idea of what was (or even if there was) Australian literature changed very rapidly from the 1890s on, and your reviewer was probably responding to the boosterism of the Bulletin years.

A side issue: Leslie was a “British suffragette, writer and pacifist”. I checked, because the Pankhursts/suffragettes were pro war (and Miles Franklin who was largely anti was in a different suffragist organisation). Further down the wiki article it clarifies that Leslie broke with the Pankhursts on the outbreak of WWI.

Thanks Bill, glad you loved my highlighting these women, and thanks for checking into Leslie a bit more. I assume you hadn’t heard of her either?

I was also going to comment on the second about what makes an Australia novel. What I take from the author’s quote is that there is a snootiness with which some circles define the literature of a country, but I agree with the author. You cannot separate yourself from where you are from, as what you know and the culture you’ve learned are ingrained. I wonder if what the author says is also in defense of indigenous writers, too, or if they weren’t even a thought at the time.

Thanks for this Melanie. Love that you engaged with this question. My feeling is that the reviewer is referring to the ongoing debate about what is Australian literature. I didn’t sense a snootiness so much as the ongoing fear that Australian literature was either being disregarded OR trying too hard to be Australian. I felt the reviewer was saying – but I might be wrong – relax, if you write from a place you will by definition write of the place, but that what makes writing great is that the wider concerns are more universal. In other words, focus on your ideas because the Australianness will we there as you are Australian.

As for Indigenous authors I’d say it was most likely the latter. I don’t think they were (much) thought of back then.

I would read that Lit bio too!

Thanks Brona. We should all put out feelers to those biographers we read!