I concluded last week’s Monday Musings by saying that I wasn’t finished with 1970. There are several posts I’m hoping to write, drawing from my 1970 research, but I’m starting with this one simply because it picks up on a comment I made last week.

That comment referenced George Johnston, and a review by John Lleonart of Barry Oakley’s A salute to the Great McCarthy in The Canberra Times (8 August). I wrote that Lleonart had some “niggles” about the book but concluded that Oakley had “given us in McCarthy a classic figure of Australian mores to rank with George Johnston’s My brother Jack“. I didn’t, however, share those niggles. He wasn’t the only one with “niggles” about the book he was reviewing, so I thought to write a post sharing some of the criticisms reviewers expressed, because they are enlightening about what was and wasn’t liked in writing and about the art of reviewing itself.

Lleonart starts his review by saying that “it’s a pity Barry Oakley shaped up for his new novel in the cultural cringe position”, and goes on to say that

Oakley could have scored both for Australian literature and the game had he followed the elementary rule that there are no beg pardons.

Instead of striding, chest out and blast you Jack after the ball, he tends to prop, apparently listening for the footsteps of intellectual hatchetmen.

But, these are not his main “niggles” (as he calls them). They include that, while “Oakley has a lot of natural ability with words … sometimes he carelessly drops into cliches”; that some of the characters are “cardboard”; and that the novel’s “social attitudes” look back to those of Lawson. Lleonart concludes, however, on the positives, which include not only the aforementioned reference to Johnston’s novel, but that our footballer protagonist McCarthy “finds in fiercely competitive sport a means of expression and, in its best moments, even a sense of the inner poetry of life.”

Suzanne Edgar, whose poetry collection The love procession I’ve reviewed here, wrote about two recent novels in The Canberra Times (March 7). She suggested that they had “appeared in answer to Thomas Keneally’s demand for acceptable middle-brow Australian fiction”. But,

The trouble is that only people who are serious about reading are likely to pay $3 and more for a hard cover book. If you pay that you are not usually after the sort of light-weight escapist stuff that can be had for 80c from any newsagent’s shelves.

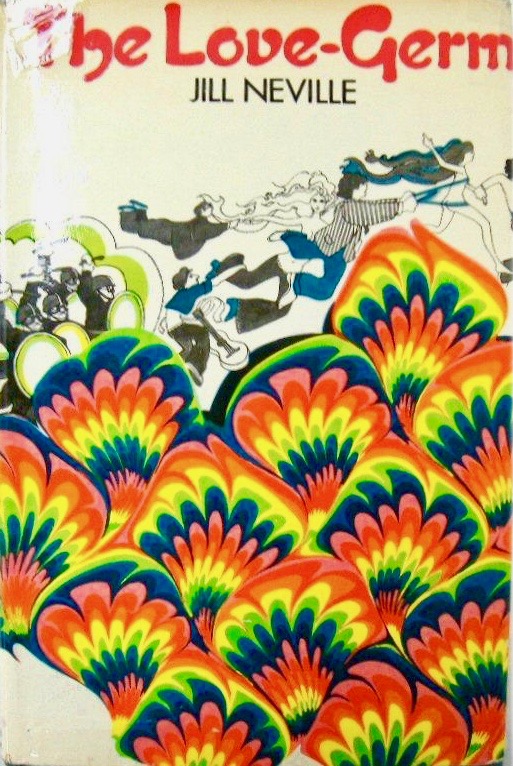

Unfortunately, Jill Neville’s The love germ and Keith Leopold’s My brow is wet are just “simple, uncomplicated bed-time stories”. Neville, Edgar continues, writes “like a slick and practised copy writer slinging words and fashionable ideas around with studied, gay abandon and not too much discretion; ‘desorified’ is one of her more flippant coinings”.

Leopold’s book, on the other hand, is “your academic’s pipe dream, the clever, but of course tongue-in-cheek crime story relieved by satiric treatment of Australian ivory towers. The sort of thing they would all like to write if they were not so busy publishing or perishing six days a week”. Edgar then goes on to say that “Mr Leopold’s unexceptional thesis is that there is dishonesty in all of us”. She gives a brief run-down of the plot – which sounds basic on the face of it – and concludes that it’s “amusing enough, but not really solid value for your money”. So, overall, entertaining enough reads but not worth buying in a $3 hardback. (That said, don’t you think that Weidenfeld and Nicolson’s 1969 hardback cover for The love germ is pretty gorgeous!)

Finally, there’s Margaret Masterman, also writing in The Canberra Times (May 30). She reviews Colin Theile’s adult novel, Labourers in the vineyard. The review is headed “Novel improves as it goes along”. Masterman starts by quoting from the novel, then writes:

After encountering this rhetorical blast on page two of Colin Thiele’s latest novel nothing would have persuaded me to read the remaining 245 pages had I not, as a reviewer, been paid to do so.

But, she is being paid, so she continues:

As Mr Thiele gets a firm grip on his narrative however, it becomes clear that such assaults upon the natural resources of the English language are only the occasional excesses of an eloquent and highly inventive writer, one moreover who is directed by a positive if imperfectly sustained artistic purpose.

She tries to place the novel within a wider literary tradition. She suggests that Thiele “conceived Labourers in the vineyard on the lines of the traditional regional novel”, and says that

Focusing his story on a long-established German settlement in the Barossa Valley … he aims as I see it to invest “the valley” with something of the imaginative presence of Scott’s border country, George Eliot’s midlands, Mauriac’s sands and pine forests around Bordeaux, and above all Thomas Hardy’s Wessex.

She then compares the novel with Hardy’s Wessex novels, writing that

Into a modest 247 pages he has organised a remarkable variety of fictional material, much of which is nostalgically familiar to lovers of the Wessex novels. His plot is highly contrived and marked by melodramatic coincidences. The moods and predicaments of his characters are closely related to their rural environment and commented on by a chorus of humorous rustics.

Masterman discusses the book at some depth, pointing out its strengths but also its failings. Seasonal festivals and country trials, for example, “are vigorously and sometimes brilliantly described” but Thiele fails to “infuse the countryside with any genuine imaginative significance”. Because of his detailed knowledge of the region, he does give his story “an illusion of reality”. Her conclusion, however, is qualified. She’d clearly much rather be reading Hardy!

I enjoyed Labourers in the vineyard as a lavish and well organised entertainment which stirred memories of the people, the woodlands, the heaths and milky vales of a great novelist whose works in these days are too often neglected.

These are just three examples I found in my research, but they nicely exemplify some of the things that are important to me when I think about my reading. What is the writing like? How does the novel fit within its perceived “genre” (defined loosely)? How relevant is the novel to the concerns of its day?

What do you think?

Another interesting spinoff from the 1970 Club. Appreciate your in-depth research. As I mentioned in one of my comments, forgot whether it’s here or in Ripples, I like the older years more. Now, I’m excited about the next year club: 1952. This one I think I’ll dive in.

Thanks Arti … you did say that somewhere. And yes, I love the 1952 year. Trove will be fun for it too … and I have a few books I want to read from that year!

Somewhat flippantly (my most frequent modus operandum), I can only say I’m greatly relieved that I’d never read a review like any of those and think you had written it, ST.

I think the fact that you are relieved is a compliment MR! I know some people think I am always positive but I feel I do have nuance in my reviews so that people can see differences in my responses to what I think about the books I read. In the end though if I review a book I do want to be kind. I like generosity as a value.

I do understand though that if you are a paid reviewer and are given books to review you can be caught. Edgar’s point was interesting … she was saying these are perfectly fine paperback reads but not value for the money you pay for a hardback. Which I guess leads us into another whole discussion!!

Picking up on a tiny point: I think that reviewer was completely wring about The Love Germ. It’s an excellent comic novel about the 1968 Paris uprisings in which gonorrhoea (or maybe chlamydia?) spreads among the students in parallel with revolutionary fervour. The fact that it’s funny doesn’t make it any less serious. The fact that I don’t remember any detail says more about my memory that it does about the book

completely wrong – but hand-wringingly so

Haha … I didn’t even notice that typo. I think I’d better leave it now…

Oh that’s interesting to hear Jonathan. That explains the title! I love the cover too. Sounds like the reviewer didn’t think it funny more perhaps than that she didn’t appreciate that humour can be serious?

I think you’re right. Jill Neville was slightly older than the students of 68, but a fascinated sympathetic ibserver

I’m intrigued to read it now Jonathan!

Oh, to live in a time when paperbacks were 80c and hardbacks were a thing 🤣

Haha kimbofo. I wondered if anyone would comment on that!

I’m interested that Keneally demanded acceptable Australian middle brow fiction, which after a promising start as a literary writer is what he has mostly delivered.

Yes, I know, I thought that was interesting too. I wonder his original statement can be found on TROVE (though of course if it was reported by SMH etc it’s not on Trove yet.)

Oh my, the cover for Love Germ is so quintessentially of its time!

Isn’t it though (as my son would say). It’s just gorgeous, I guess because I can relate so closely to that design style from my teens. Thanks, Marcie.

I giggled after reading this post because my poor mom (Biscuit!) was part of a book club that met in a bookstore, so members were kind of expected to buy the next month’s book from the store itself. Well, the club chose Britney Spears’s memoir, which was a hot release in the U.S., but it was initially printed only in hardcover. Each chapter was soooo short, that really, the book was likely 50 pages shorter than it really seemed. Therefore, when I read the comment about “only people who are serious about reading are likely to pay $3 and more for a hard cover book. If you pay that you are not usually after the sort of light-weight escapist stuff….” had me in stitches. My poor mom was so disappointed in getting cheated by Britney! I want say she paid $30 or more…

I’m glad this story spoke to you Melanie. I feel for Biscuit. It does sound like a bit of sleight of hand by the publisher to bulk up the book.

I read with interest your previous post and this one as I have sitting unread A Salute to the Great McCarthy along with another Oakley book of short stories called Walking Through Tigerland. Footy seems to be a theme I am guessing. I also have Behind the Front Fence : 30 Modern Australian Short Stories that he edited. There are a few interesting authors in that compilation, Janette Turner Hospital, Nick Earls, David Malouf and Jessica Anderson to name but a few.

I have read his Let’s Hear It For Prendergast and checked my 2 star review at GR that said “A satire on the literary community in late 60’s Melbourne. This was first published in 1970 but has not stood the test of time. It had some witty moments that gave me the occasional laugh but it dragged too often and in the end had a rather stupid conclusion.”

Oh thanks for all this fourtriplezed. That short story collection sounds great. I’ve certainly read all those authors.