Once again it’s Karen’s (Kaggsy’s Bookish Rambling) and Simon’s (Stuck in a Book) “Year Club” week. This week, it is 1970, and it runs from today, 14th to 20th October. As for the last 6 clubs, I am devoting my Monday Musings to the week.

Despite the excitement and idealism of the 1960s, 1970 Australia was strongly conservative, politically speaking, with some notorious conservative leaders (like Joh Bjelke-Petersen, Sir Henry Bolte, and Robert Askin) being premiers of their respective states. But, there were exceptions. The socially progressive Don Dunstan became premier of South Australia during the year, and, while our Prime Minister, John Gorton, was a conservative, he was recognised as a supporter of the arts.

The war in Vietnam was still underway but was becoming increasingly unpopular. This was the year Australia decided to go metric for weights and measures, and, more relevant to this post, it was also the year that Germaine Greer’s The female eunuch (which I read the following year) was published.

A brief 1970 literary recap

Books were of course published across all forms, but my focus is Australian fiction, so here is a selection of novels published in 1970:

- Jessica Anderson, The last man’s head

- Richard Beilby, No medals for Aphrodite

- Richard Butler, Sharkbait

- Diane Cilento, Hybrid

- Jon Cleary, Helga’s web

- J.M. (John Mill) Couper, The thundering good today

- Geoffrey Dutton, Tamara

- Catherine Gaskin, Fiona

- Shirley Hazzard, The Bay of Noon

- Edward Lindall, A gathering of eagles

- William Marshall, The age of death

- Cynthia Nolan, A bride for St Thomas

- Barry Oakley, A salute to the Great Macarthy AND Let’s hear it for Prendergast

- Dal Stivens, A horse of air

- Colin Thiele, Labourers in the vineyard

- Ron Tullipan, Daylight robbery

- Barbara Vernon, Bellbird (based on the ABC television series)

- F.B. Vickers, No man is himself

- Patrick White, The vivisector

A few of these writers are still respected and read today; a few are known but read less frequently; while some have fallen out of public consciousness (to my knowledge, anyhow!)

Of those I didn’t know, a couple caught my attention for their subject matter. F.B. Vickers is one. Trove describes No man is himself as “A novel set in the north west of Western Australia concerning an officer in charge of Native Welfare who is sympathetic to Aborigines but involved in personal difficulties with the white community and his wife.” The other is Edward Lindall whose A gathering of eagles is also set in Western Australia, and has a First Nations character. Google Books describes it as a “thriller set in the remote barren wasteland of north western Australia; an outcast Aboriginal woman, Ilkara, assists the survivors of a murderous plot to outwit their would-be killers.” The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction says Lindall was the pseudonym used by Edward Ernest Smith (1915-1978). He is also listed at a Classic Crime Fiction site.

Writers born this year include novelists Julia Leigh and Caroline Overington, and those who died include Herz Bergner (whose Between sea and sky I’ve reviewed), children’s fiction writer Nan Chauncy, Frank Dalby Davison (who was part of “the triumvirate” with Marjorie Barnard and Flora Eldershaw), and George Johnston.

There were not many literary awards, yet, though the state awards we know were getting close. And, several of the main awards made in 1970 weren’t to fiction. The ALS Gold Medal, for example, went to historian Manning Clark, and the Colin Roderick Award to Margaret Lawrie’s Myths and legends of Torres Strait.

There were some fiction awards, however, including of course, the Miles Franklin Award, which went to Dal Stevens’ A horse of air. The trade union-supported Mary Gilmore Award (my post on this award) was made to Keith Antill for Moon in the ground. It’s an Australian science fiction story set around the secretive Pine Gap near Alice Springs. The “$1,000 Rothman’s award for the best Australian novel of 1969” was awarded in 1970 to George Johnston‘s “semi-autobiography Clean straw for nothing” (from Trove).

The state of the art

As for previous club years, I checked Trove to see what newspapers were saying about Australian fiction. This was a little trickier for 1970 because, due to copyright, many newspapers from this time have not yet been digitised. However, some papers, most notably The Canberra Times and Tribune, along with some regional ones, have made their content available to Trove. To them I am most grateful.

George Johnston

If one name loomed large in my my 1970 Trove research, it was George Johnston, and not just because he died in July. There were, of course, the obituaries, but, unrelated to his death, is his being used as a benchmark by commentators. For example, John Lleonart, reviewing Barry Oakley’s A salute to the Great McCarthy in The Canberra Times (8 August), has some “niggles” about the book but concludes that “Oakley has given us in McCarthy a classic figure of Australian mores to rank with George Johnston’s My brother Jack“.

Meanwhile, in discussions about the need for more Australian content on television, the television miniseries of My brother Jack was suggested as a benchmark for good Australian television content. Frances Kelly, writing in The Canberra Times (August 26), discusses the economic and artistic challenges to producing more “good” Australian content, and suggests one solution could be for Australia to

follow the BBC’s lead and begin work on adaptations. There are many fine Australian novels, which if we must still fly the flag, would bear dramatisation. My brother Jack was a shining example.

The obituaries sum up Johnston’s career well – at least as it was seen at the time of his death. Maurice Dunlevy writes in The Canberra Times (23 July) that:

He had come back to his gumtree and kookaburra womb to find a new land, a people without a soul, and some uncomfortable ghosts from his past. “I would like to help Australians to find a new identity, a new soul, a new spirit”, he said on television. But to do so he had to sort out his own attitude to a country where he had left “the irrecapturable rapture of being young”. He was trying to do this in the third volume of the trilogy [A cartload of clay] during the past year.

Roger Milliss discusses Johnston at some depth in Tribune (12 August), concluding that

the important thing is the task that George Johnston recognised and set for himself — that of modernising Australian literature, of dragging it screaming into the 1970’s, of giving it a shape consistent with the world around it. That task must now be taken over by someone else — perhaps a writer who will emerge from the ranks of this new emerging generation.

These two obituaries make good reading if you are a Johnston fan.

Bookworm diggers

Meanwhile, over in South Vietnam, reported the Victor Harbour Times (May 29), Australian soldiers were well supplied with most amenities, but were running short of reading material. They had, says the report, “ample supplies of newspapers and regularly published magazines” but “novels, other books and paperbacks [were] in short supply”. Donations were being called for, and the Army would deliver them.

Australian classics

Publishers publishing classics is not new, but it’s always interesting to see “what” publishers see as those worth publishing at a particular time. In 1970, the Australian publisher Rigby published two Australian classics, Rolf Boldrewood’s Robbery under arms and Marcus Clarke’s For the term of his natural life, in $1.25 paperback editions. The Canberra Times (May 30), described them as “quite massive little tomes as paperbacks go” but said they gave readers “the opportunity of owning at a reasonable price two books that will be read and reread as long as Australian literature survives”. I love the qualification, “as long as Australian literature survives”. I wonder what the reporter thought might happen? Anyhow, these are still recognised “classics” but more have been added to the Australian classics pantheon since then.

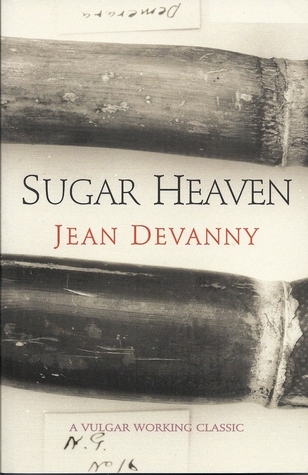

While not quite making classics status, two other authors from the past were mentioned in the year’s papers. One was Communist Party member, Jean Devanny, whose papers were donated by her daughter to the University of Townsville. (I included her in my post on women writers and politics in the 1930s.) The Tribune‘s report (January 28) says that Jean Devanny had had more than 20 books published by Australian and overseas publishers. One of her best known, Sugar heaven (1936), is a novel of class and politics on the Queensland cane fields, and was published in the Soviet Union in 1968.

The other author, Vance Palmer (1885-1959), came from the same era, and while not a Communist, was left-leaning politically. By 1970, he was seen as old-fashioned, but Professor Harry Heseltine thought he was due for a reassessment, and published his Vance Palmer in 1970. I will share more about this in another post.

Censorship and Book Bans

“Australia is still the country of interfering and sometimes ridiculous censorship, but there are signs of vitality on the cultural scene” (Paris newspaper Le Monde, The Canberra Times, December 21, 1970).

The last book banned in Australia was Philip Roth’s Portnoy’s complaint. It was banned in 1969, but after protestations by booksellers and publishers, and two trials in New South Wales which ended in hung juries, the ban was lifted in 1971. In 1970, however, it was all still happening. There’s way too much reporting for me to cover here, so I’m just to entertaining references to whet your appetite.

The University of New South Wales’ student newspaper, Tharunka (April 21), devoted a special literary supplement to the issue, asking writers to comment on censorship. One was Thomas Keneally, who commenced his piece by saying he felt “uneasy contributing to a forum on censorship because I have never achieved banmanship”. He is tongue-in-cheek about the reasons for the ban, which had to do with its being a “dirty” book. Keneally doesn’t see orgasm as “the key to the vision of man”, and argues that “there is very little of less value to the novelist than a person enjoying himself”. Fair point! Nonetheless, despite his “spinsterish views on eroticism in literature”, he thinks the ban is “an embarrassment”.

Maurice Dunlevy takes satire further in his article “The Portnoy tug-of-war” (The Canberra Times, September 5). Do read it … And, for a more recent history of the saga, check this article by Sian Cian in The Guardian (February 2, 2022). She quotes Des Cowley, of the State Library of Victoria:

“There’s been a lot written about the whole saga with Penguin and the legal case, but a little part of that story is that a small group of people got together and defended the right of literature to exist. It is such a beautiful case because, in a way, it ushers in the change Australia saw between the 1960s and 70s, with the progressive Whitlam government, and going from a literary backwater to a world stage.”

I’m not finished with 1970 … but this post is long enough. I’d love to hear any thoughts you have about the year, or about the stories I’ve shared here.

Sources

- 1970 in Australian Literature (Wikipedia)

- Joy Hooton and Harry Heseltine, Annals of Australian literature, 2nd ed. OUP, 1992

Previous Monday Musings for the “years”: 1929, 1936, 1937, 1954, 1940 and 1962.

Do you plan to take part in the 1970 Club – and if so how?

Well, my beloved second-eldest sister – who was more like a mother, in truth – was involved in the court case for Portnoy’s Complaint and appeared on the stand in defence of it ! It was all terribly exciting, back then.

<I love the qualification, “as long as Australian literature survives”. I wonder what the reporter thought might happen?> I feel that the quote isn’t made in the conditional but merely a … a time limit ? Know what I mean, ST ?

Oh, that must have been exciting MR. I was at university and too focused on my studies to have more than a general awareness of it all, which is silly given I was studying English literature! I guess I agreed with the freedom philosophy but was too engrossed in MY reading to follow the actual case.

Hmm, I think I know what you mean, as in “IF” Australian literature survives versus “HOW LONG” it might survive for? Is that what you are saying? Does it materially change my question do you think? I was thinking in terms of time period, as in does he see an endpoint to Australian literature? I guess it’s just a rhetorical throwaway, but I thought it sounded odd. And, of course, it’s a big call to say that these will be classics essentially way into some indeterminate future? I think I’m getting bogged down!

I like this person’s take on censorship: “Nonetheless, despite his “spinsterish views on eroticism in literature”, he thinks the ban is “an embarrassment”.” Basically, it’s the good old “if you don’t want to read it, don’t read it” argument that almost seems too simple. To those who think they can get a book banned so no one (particularly the children!) can read it, what do you think you’re doing? Are you able to control any other facet of a stranger’s child’s life??

Thanks Melanie. This person, Thomas Keneally, is in fact a prolific Australian novelist. He’s won the booker (for “Schindler’s Ark” which became the film “Schindler’s list”) and wrote some innovative and confronting books in his time, but has now settled more into more “accessible” historical fiction. I wondered about his “embarrassment”. The way he wrote it seemed to continue the vein that he was “embarrassed” that he hadn’t written anything himself worth banning! But I wondered if he also meant it was an embarrassing thing for Australia to do and be known for!

I think he meant that even if something was too much for him, it’s embarrassing that someone would ban literature based on his (or anyone else’s) dislikes.

Yes, that sounds a fair interpretation Melanie. Thanks for the thought you’ve put into this.

1970 is also notable as the one year I had a story published – a short story about Melbourne consumed by rising sea levels – in the RMIT Engineering students magazine (I forget its name).

I probably wrote some anti-war material for SDS as well. Later in the year I was arrested on the steps of the GPO for ‘publishing material to incite a breach of the law’, ie handing out pamphlets, and held for the rest of the day in the cells under the old magistrates court (which I’m thinking also saw Ned Kelly).

Around that time I read Clean Straw, which I regret, Johnston is a braggart; and also Barry Oakley. But none of the others, I don’t think

Oh well done Bill. So, you were writing cli-fi before it became a thing! Do you still have your story? You have certainly had some experiences in your career. I do hope you are writing your memoir.

I haven’t read Johnston as I fear he might be “too blokey” though I’m sure he has some valid things to say about male culture of the time. Has it changed? As for Barry Oakley, I remember that novel coming out but it didn’t grab my attention. In 1970 I was too engrossed in English lit from Austen to Woolf and Forster. (That was the sort of span our first year English course did.)

I don’t know that Anderson. I remember Gaskin being very popular at the time, but I wasn’t into historical fiction either. However, a couple here are intriguing and I do hope to explore them a little more in coming weeks.

I just realised I lied! In 1970 I was still at school, and I read Patrick White’s Voss. Not The vivisector, of course, which only came out that year, but at least something contemporary. I then read, under my own steam, his short stories, The burnt ones.

Thanks for such a detailed post for the 1970 Club, WG. I admit I know nothing about books published in 1970 Australia. So, your post is a wonderful resource. 1970 was monumental for me, why, that was the year I came to Canada from Hong Kong with my family, starting a totally different life. As a young teenager, the book published that year which impressed me most was Jonathan Livingston Seagull. Still remember the photos and the idea of flying high and not satisfied with being a garbage pecking common gull. Well, so much for the impressionable young mind. 😉

Haha Arti, I remember that book. Thanks for sharing a bit of your story. You’ve been in Canada for a long time now!

More than half a century. Lots and lots of memories, especially the early years of settling in as a high school student then at university. I don’t think I’ll join the 1970 Club this time. I kinda like the older year clubs more. Also too many books to read currently.

I have lots of memories of moving in my early teens too – from a remote outback Queensland town to Sydney. Not quite Hong Kong to Canada but a big change all the same – in 1966. Those years are big years aren’t they, so things that happen in them tended to make big impressions. I’m a bit like you. I do like the earlier years more.

PS 1970 was my last year of school so I was an older teenager … I think I said on another comment that I was at university, but I lied … a senior moment … haha

Haha I wasn’t too much younger. Started grade 10 in high school. Just saying ‘young teenager’ to mislead. 😉

A little obfuscation never goes astray. Unfortunately, my error about being in university that year obfuscated in the wrong direction – haha!

PS I keep thinking you are about 40!! Then every now and then I realise no, you are a little older than that.

Obfuscation is the right word. And if you think I’m in my 40’s then my

obfuscation works. 😆

I try to present a neutral image in terms of age, gender, and race, in order to appeal to a wider audience / readership on Ripple. For I believe there are some things that are universal, beyond borders, especially as we talk about ideas, books, and films.

Yes, I agree… I tried for a while, particularly re age so I wouldn’t be put in a box, but it gets hard and you just have to hope that the “real” people will stay with you.

Thanks for a terrific post, Sue. I just checked the little notebook where I listed the books I read in 1970. I read 130 books! I was doing Eng Lit Honours year at Sydney Uni, but a lot of the books weren’t connected to study. Of the titles on your list, I read the Two Barry Oakley books and The Vivisector.

Oh my Jonathan … you really were up to date with your reading that year. Did you enjoy the Oakleys? I’m guessing you remember all the Portnoy stuff?

What was your honours topic?

And yes, I remember all the Portnoy stuff. I remember David Makouf, then newly returned from Britain to take a job as lecturer at Sydney University, telling a joke about a woman who, introduced to Philip Roth at a social event, recoiled in horror when he offered his hand to shake

Oh that’s funny … where has that hand been!!

I did enjoy the Oakleys. He came close to describing my social environment. I remember one scene when someone arrives at a party and holds out a bag of marijuana, calling it the Eucharist of the new middle classes. That struck me as note. My thesis was on the poetry of George Herbert, but I studied AustLit with Leonie Kramer

It’s great when you feel your environment has been captured isn’t it. Herbert! I see your interest in poetry goes way back.

I don’t understand why I didn’t do AustLit as I loved it at high school and Thea Astley was a tutor at Macquarie. I think we just had too many options.

Fascinating as always Sue…I even discovered a distant relative of Mr Books’. Richard Beilby is his first cousin twice removed.

Thanks Brona … how interesting. Richard Beilby’s name rang a bell for me.

Hi Sue, I don’t think I ready any of those novels in the 70s, and only a few in later years. I was married in 1972, and had two children by 1975, so not much time for reading. I vaguely remember the fuss about Portnoy’s Complaint. The 1970s, was when social change and debates were prominent, and literature was also having an impact.

Thanks Meg … you were clearly a child bride! I can imagine with all that going on your only vaguely remembering the Portnoy fuss. But you are right, things got on the move in the 70s didn’t they, with Whitlam’s election etc.

Very interesting! The only one of your list I’ve come across is The Female Eunuch, which I would have liked to re-read but I don’t think I have time now. I chose it for my Service to the School Prize in 1989 as I left school, thinking I was terribly daring, but of course our headmistress was an old-school feminist and probably approved hugely!

Oh I missed seeing this Liz. Sorry. I would like to have reread The female eunuch too. It informed much of my feminist thinking – for good or bad! I love that you chose it for your school prize, in 1989! That’s great.

A really interesting post and thank you for sharing this – I am woefully ignorant about a lot of these writers so it was very informative for me. And I was intrigued to see that Catherine Gaskin was on your list, as she was one of my mother’s favourites!

Thanks Karen … I love that you recognised Gaskin. She was very popular in my young days with older generations. She was born in Ireland but grew up here though I think moved overseas early in her publishing career. I happen to have a signed copy of a book of hers through Mr Gums grandfather who was a journalist.

Yes, I think of her in a kind of grouping with Victoria Holt, Jean Plaidy and the like – my mother used to devour those. And how lovely you have a signed copy!

Exactly … that’s where I place her too!

PS if you were interested in following up any of these writes, I would say Jessica Anderson would be worth it (though I don’t know this book. But Tirra lirra by the river is great.)

Thank you! 😀

It’s a great year to explore: I wish I’d planned to write something like this for CanLit! Although I always appreciate the Clubs, I particularly enjoy the diverse options available with these “later” years. I’ve not read any of the books published in that year that you’ve listed, and probably most Australians haven’t read any of the big Canadian books of that year either (maybe Robertson Davies Fifth Business would be the best known, Margaret Laurence’s short story collection A Bird in the House for those who favour women’s writing, and I’m reading Mavis Gallant’s A Fairly Good Time, which is virtually unknown).

[BTW, I made an error with my feed reader and lost a lot of folders, which means I’ve missed some posts, but I’m back on track now.]

No worries Marcie about the post-missing. I’ve been travelling much over the last six weeks, so I’m not up-to-date either on posts.

I think I like the earlier years more though they can be challenging to find something to read.

Canadian literature. I have read one Robertson Davies (his last, from 1994) and some Margaret Laurence (from 1964). But from memory, probably the closest to 1970 that I’ve read is Mordecai Richler’s essay collection Shovelling trouble. Read that in 1974.

Well, I do HAVE a copy of Patrick White’s The Eye of the Storm, from 1973, and I do intend to read it, but I’ve only actually read The Aunt’s Story (1948).

Only the Richler afficionadoes have read those early essay collections, so you deserve a badge for that obscure selection. heh

I think both Simon and Kaggsy have expressed a preference for the earlier years, too. And there’s something to be said for having fewer options; my list for 1937 was a single page, whereas I gave up on making a list for 1970.

Re your last paragraph, it’s partly because I like the fewer options but also partly because I’m really interested in those years, particularly the 1920s to 1940s.

Asperula there’s an interesting story to why I read this. It was because I met a Canadian in a youth hostel back in Tasmania in the 1970s. He had just read the novel and gave it to me because I expressed interest. I really enjoyed it and I still have it. I’d love to read it again really.

In America, Mad Magazine did a takeoff of the movie made of Roth’s short novel Goodbye, Columbus. Its successor did get a mention towards the end, as “Pitney’s Complaint”, and the whole bit was packaged as “The Gripes of Roth”.

I think that Keneally was not wrong. I read Portnoy’s Complaint within a decade or so of its publication, and have no particular desire to read it again.

Haha George love it. The Gripes of Roth in particular!

As for Keneally, I know what you mean. I have strong recollections of going to the theatre in the 1970s, for example, and the audience laughing, laughing just at the use of the “f” word! I needed more humour than that.

This reveals to me how little I know about literature outside the US. I have not heard of any of these titles and I’ve only heard of one of the authors. Sad.

I guess that author is Patrick White, Deb? Most of the others are probably not well know out of Australia. Oh, or maybe you know Shirley Hazzard as she spent much of her adult life in New York? I would probably know some American writers of that time, but it is sad how little depth we really do have in other national literatures isn’t it.

It is Shirley Hazzard. And even though I have heard of her, I’ve never read anything she has written.

Yes, quite sad.

Thanks Deb, it suddenly occurred to me that it was probably Hazzard because of her residence. The reason I first suggested Patrick White is because he’s Australia’s only Nobel prize-winner in literature (albeit in the early 19790s) so some people from other countries do know him – hence he was my first thought!

Such an interesting post as ever, Sue. My knowledge of Australian literature is terribly poor, but it’s fascinating to see an overview of this literary year from your perspective. Shirley Hazzard has been on my list of authors to try for a while, so I’m taking this as a nudge!

Thanks Jacqui. I thought I’d replied to this but clearly not. Shirley Hazzard is worth reading. I’m reading another now, in fact,