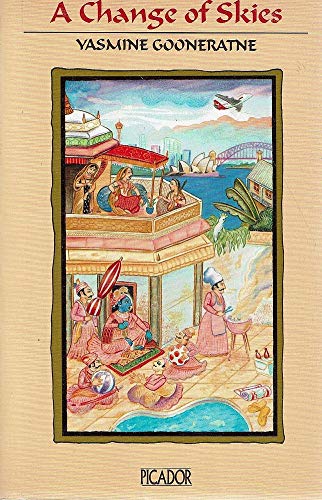

It was through the Jane Austen Society of Australia’s (JASA) newsletter, Practicalities, that I learned of the death of Yasmine Gooneratne, a woman with whom I have crossed paths – one way or another – three times. She was an academic at Macquarie University, where I did my undergraduate degree; she wrote a novel, A change of skies (1991), which my reading group discussed back in 1996; and, she was the patron of JASA (and you know how I love Jane).

You can find quite a lot about Yasmine Gooneratne on the Internet, if you are interested, so I’m just going to focus on a few points that struck me, and I hope will interest you.

“No nonsense”

A site called The Modern Novel provides a useful potted biography, so I will start with that. It says that she was born in Sri Lanka (then Ceylon) in 1935 as Yasmine Bandaranaike, which means she was “a member of the well-to-do Ceylonese family which included Sirimavo Bandaranaike, the first woman prime minister in the world”. She studied at the University of Ceylon and Cambridge University, and in 1962, she married the doctor and environmentalist Dr Brendan Gooneratne (who died in 2021). They emigrated to Australia in 1972, where she lived for 35 years, according to Wikipedia, before returning to Sri Lanka. It was here, in her home country, that she died on 18 February this year.

AustLit provides more detail, which includes that she was founding Director of Macquarie University’s Post-Colonial Literatures and Language Research Centre from 1989-1993, and that she was awarded an AO (Order of Australia) in 1990 “for her distinguished contribution to Sri Lankan and Australian literature”. She won (or was listed for) a number of awards in Australia and elsewhere.

Gooneratne wrote over twenty books, including novels, some poetry and short story collections, as well as many works of non-fiction, but she seems little known outside academic circles (and JASA). Indeed, my initial – and general – search for this post brought up many references to her but no news items on her death. I had to search a little more specifically for that. This was interesting given that, on the several internet sites I found, she is described as widely known. DBpedia* calls her a “Sri Lankan poet, short story writer, university professor and essayist” and says that “she is recognised in Sri Lanka, Australia and throughout Europe and the U.S.A., due to her substantial creative and critical publications in the field of English and post-colonial literature”.

When I did find something about her death, I was delighted to find an obituary written by her daughter Devika Brendon. Initially posted in the Sunday Times on 18 February 2024, it has been shared on many other sites including the blog I am quoting from. It provides a loving and personal tribute to her mother, but one which I suspect also rings true to the person Gooneratne was. Devika Brendon tells us that:

Yasmine Gooneratne as a private individual left clear instructions about what she wished regarding her funeral. Her directives show a great deal about her character and her values. ‘No public notices. No public viewing. No public funeral. No memorial lectures. No fuss. No feathers. No posturing. No performativeness. No photographers. No selfies. No celebrities. No nonsense.’

I have mentioned Gooneratne a few times on this blog, including in a brief Monday Musings post I wrote in 2013 on Migrant literature. It had been a long time since I’d read A change of skies (and it’s even longer now), but I wrote that the novel was about “educated middle class migrants – like herself I presume – who work to find a balance between fitting into the new culture while at the same time preserving their Sri Lankan identity”. If you want a better flavour of this work, check out this post written in 2012 by someone called Elen on a blog called the southasiabookblog. Elen says that Gooneratne’s “portrayal of the immigrant experience is as funny and poignantly ironic as Jhumpa Lahiri’s work on a similar topic is earnest”. I wish I could remember it that well, but I read it when I was immersed in parenting and my memory is general. This description of Gooneratne’s tone, however, sounds like the writing of an Austen-lover!

I will end with another paragraph written by her daughter because, not only does it tell us a lot about Gooneratne but, if you are an Austen fan, you will love the final line:

She had great contempt for hypocrisy and cruelty. She had a great sense of humour and a lively sense of fun. As she was a person of moral integrity, the repulsive conduct of people who prey upon the vulnerable saddened her, especially as she grew older. While always choosing to believe the best in people, she found herself unable to accept the lies that are spun by opportunists and predators on a daily basis. Her good opinion, once lost, was lost forever.

* DBpedia describes itself as “a crowd-sourced community effort to extract structured content from the information created in various Wikimedia projects”