“I love a factory novel”! So wrote Buried-In-Print blogger Marcie on my post earlier this year on the Australasian Book Society. I do too, I replied, and noted to myself that this could be a topic for Monday Musings. I have not done as much research as I would have liked, but I figured I never will, so why not just provide an intro and then call in all of you, the brains trust, for your contributions.

Factory novels are, essentially, a subset of working class literature. They emerged in the 19th century as a result of the Industrial Revolution. They critiqued the exploitation of workers, and identified the poverty and social problems that accompanied industrialisation. Some also explored attempts to improve the situation. Dickens was a major exponent of writing about social problems, but one that made a big impression on me was Elizabeth Gaskell in North and south (read before blogging). Her Mary Barton (on my TBR) also falls within this group.

I love factory novels because the best are written with such heart and passion, with such desire to bring about change. As I’ve said before, I don’t believe literature (or any art) has to do this, but I enjoy art that does.

Selection of Australian factory novels

This small selection includes novels in which factory work and factory workers are the prime focus of the story. There are many other novels which incorporate factory themes or storylines, that I haven’t included. I was so tempted to expand my definition and include other sorts of labourers, such as wharf labourers, for example, but decided to keep it to my original goal.

The books are listed in alphabetical order by author, though I did consider ordering them by date of publication (from 1926 to 2024).

- Mena Calthorpe, The dyehouse (1961) (my review): set in a Sydney dyehouse, this novel is about the impact on workers of capitalism-at-all-costs

- Dennis Glover, Factory 19 (2020): set in the very near future, 2022, it depicts Hobart, devastated by economic recession, being recreated as a new industrial colony titled Factory 19 which is fixed in the pre-digital past of the 1940s. What can go wrong!

- Rosalie Ham, Molly (2024) (Lisa’s review): prequel to Ham’s The dressmaker (read before blogging); starts with Molly helping to support her struggling family from her backbreaking work in a corset factory (when she’s not demonstrating for women’s rights)

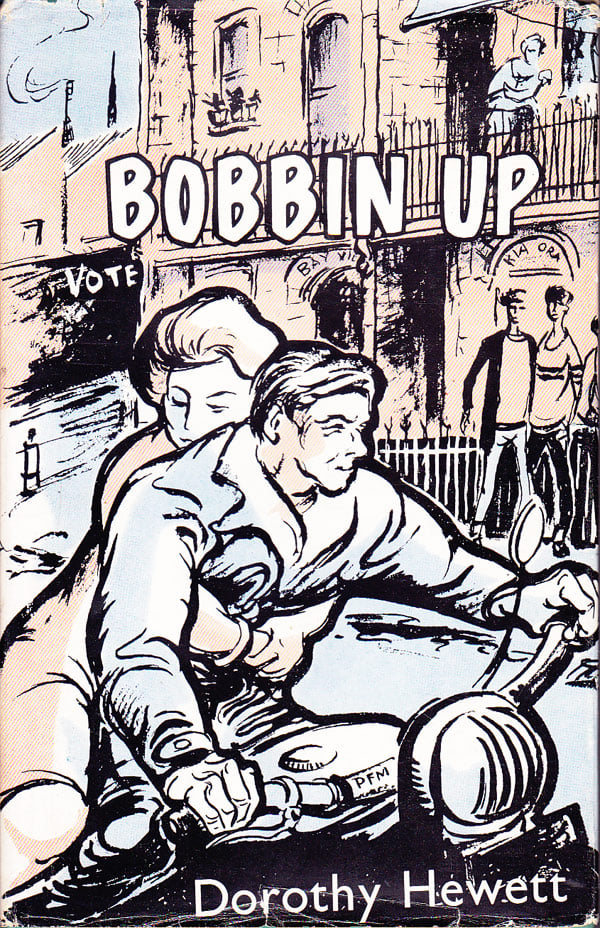

- Dorothy Hewitt, Bobbin up (1959) (kimbofo’s review): set in inner-city Sydney and about, says, kimbofo, “a bunch of hard-working women whose lives are dominated by their long shifts in the [woollen mill] factory”, not to mention the restrictions on their lives imposed by their gender.

- David Ireland, The unknown industrial prisoner (1971) (Bill’s review): set in an oil refinery, a winner of the Miles Franklin Literary Award. Text classics describes it as “a fiercely brilliant comic portrait of Australia in the grip of a dehumanising labour system.”

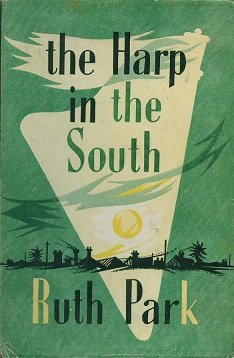

- Ruth Park, The harp in the south (1948) (read before blogging): several of the Darcie family work in factories; a warm-hearted novel in which Park documents the lives of people living on factory salaries and trying to lead a good life.

- Katharine Susannah Prichard, Working bullocks (1926): includes depictions of a timber mill, and the broader issue of working conditions and industrial accidents.

Not surprisingly, most factory novels tell their stories from the point of view of the workers. They chronicle the precarity of life when salary is low, rights are few, and there is little time or energy left for finding ways out. In some of the stories, the workers organise in the hope of forcing change and improving their lot, but our authors are under no illusion that this is easy. Most of the novels are contemporary – that is written around the time they are set – but Ham’s is historical fiction, and Glover’s is, technically, technically futuristic.

So now, my question to you is: Do you like factory novels, and would you like to share your favourites (from any nationality of writer)?