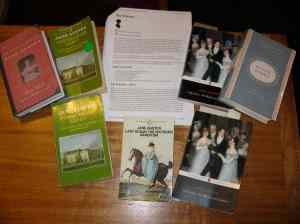

While searching Trove recently for my Monday Musings 1923 sub-series, I came across some articles on Jane Austen’s unfinished novel, The Watsons, and can’t resist sharing them with you.

I have written about unfinished books before, including on Jane Austen’s unfinished novels, The Watsons and Sanditon. Unfinished books aren’t to everyone’s taste but, if you love an author, you’ll read anything they wrote. Such is the case for me with Jane Austen.

So, The Watsons. Just as writers can’t seem to stop writing sequels, prequels and multifarious other versions of Austen’s six published novels, they are also drawn to her unfinished novels. The Watsons, for example, which Austen abandoned around 1805, has been “finished” several times. The first appeared in 1850, and was not presented at the time as a continuation. Wikipedia provides a good summary, explaining that it was an “adaptation” written by Austen’s niece Catherine Hubback, who titled it The younger sister. The initial chapters were based on Austen’s writing, but Hubback did not copy her words verbatim. The first real continuation came in 1923, and was written by L. Oulton. Since then, there have been several more, including versions of Hubback’s version! And so it goes ….

You can read all about it in the Wikipedia article above. Meanwhile, I’m returning to Trove, and the two articles that inspired this post. Both appeared in May 192 – in Melbourne’s The Age (May 5) and in Sydney’s The Sun (May 13). They refer to the publication of two “editions” that year of The Watsons – an unfinished edition with, says The Age, “a pleasant and informative introduction by A. B. Walkley”, and one completed by “Miss L. Oulton”. The Sun describes these two editions:

One firm publishes this fragment with an introduction by A. B. Walkley; the other firm actually calls upon L. Oulton to finish the story! The reader is advised to read only to the place where Jane Austen threw down her pen.

Good advice, I say – but that’s because I am more interested in Austen’s writing than in what others might think were her intentions. This, however, is not why I wanted to share these pieces. What interested me were their attitudes to Austen.

The Age says:

A return to Jane Austen after a course of modern fiction is an experience. The prim dignity of her diction; her bookish, almost stilted, conversation; her expression of fine sentiments and descriptions of good manners; her special acquaintance with the somewhat narrow insular life of the well-to-do in the English provinces a century and a quarter ago; her well-bred young ladies, whose only ambition in life is to secure husbands; her shrewd insight into the human heart, and her capacity as a storyteller— the reader renews acquaintance with much pleasure.

Not surprisingly, I don’t agree with this assessment of Austen’s writing. “The prim dignity of her diction”? Good diction perhaps, but prim? Not my Jane. Her conversation does tend to be formal compared with today’s writing, but you just have to read Lydia’s slangy “Lordy” to know that Austen can capture the nuance of character through her dialogue. Further, describing her subject matter as “the somewhat narrow insular life of the well-to-do in the English provinces” is, in fact, “somewhat narrow”. Of course, I agree with “her shrewd insight into the human heart, and her capacity as a storyteller”.

It is this – “her well-bred young ladies, whose only ambition in life is to secure husbands” – that most offends. It reduces Austen’s concerns to something not worth reading, or, to something worthy only of a few hours of escapism. Her heroines do tend to be “well-bred” in terms of manners, but many are by no means “well-to-do”. Marriage is the outcome of her novels, but her themes and her heroines’ ambitions are far more complex.

The Sun was more off-handed about why we might read Austen:

The story bears all the characteristics of the author, though it does not compare with her other established works … Through this fragment, however, the modern reader may pleasantly peer at a vanished age, with a ballroom etiquette already long forgotten, sententious speeches, a slavish admiration of “the quality” in the county, love affairs that are hidden by hints and evasions, and a painful obedience to the conventions.

“Pleasantly peer at a vanished age” and “painful obedience to the conventions”? Even in the beginning of The Watsons we see Austen’s eye for superficiality versus substance in her society, and her willingness to expose it. We also see her awareness that not all women were well-to-do, as shown in this quote from the novel. In it, our not-so-well-off heroine Emma speaks to the aristocratic Lord Osborne:

‘I wonder every lady does not. – A woman never looks better than on horseback. –’

‘But every woman may not have the inclination, or the means.’

‘If they knew how much it became them, they would all have the inclination, and I fancy Miss Watson – when once they had the inclination, the means would soon follow.’

‘Your lordship thinks we always have our own way. – That is a point on which ladies and gentlemen have long disagreed. – But without pretending to decide it, I may say that there are some circumstances which even women cannot control. – Female economy will do a great deal my Lord, but it cannot turn a small income into a large one.’

Sure, Austen’s heroines were not in the poor-house, but not all were carefree either when it came to money. Indeed, several – Fanny Price and the Dashwoods, for example – rely on the kindness or generosity of others to live in reasonable comfort. And many minor characters – such as the Bateses in Emma – were identifiably poor. Marriage was a necessity not a luxury for many (Emma’s Emma notwithstanding!)

You are welcome to check my Austen posts to see my thoughts on these and other matters.

I enjoyed finding these articles, but was disappointed to find the same-old misunderstandings of Austen in vogue then as they continue to be now.