Around ten years ago, I wrote a post on National Arbor Day. It was inspired by a Library of America story. The thing is that then I didn’t, and I still don’t hear, about Arbor Day anymore. Indeed, Mr Gums and I reminisced that it was mainly through school that we heard about it at all. Nor do I hear much about National Eucalypt Day, which I wrote about 8 years ago. I do hear sometimes about various tree-planting initiatives, but I was surprised to hear on ABC Classic FM on the weekend that Sunday was National Tree Day! A bit of research took me to the National Tree Day website.

Here, I learned that it was established in 1996, by Planet Ark, and that it has “grown into Australia’s largest community tree planting and nature care event”. The site continues that it is “a call to action for all Australians to get their hands dirty and give back to their community”. I also learned that they run three tree days, whose dates for this year are:

- Schools Tree Day Friday 25th July 2025 (set for the last Friday in July)

- National Tree Day Sunday 27th July 2025 (set for the last Sunday in July)

- Tropical Tree Day Sunday 7th December 2025

I said above that I don’t hear about Arbor Day anymore, so I checked Wikipedia. Under Australia, on the Arbor Day article, it says:

Arbor Day has been observed in Australia since the first event took place in Adelaide, South Australia on the 20th June 1889. National Schools Tree Day is held on the last Friday of July for schools and National Tree Day the last Sunday in July throughout Australia. Many states have Arbour Day, although Victoria has an Arbour Week, which was suggested by Premier Rupert (Dick) Hamer in the 1980s.

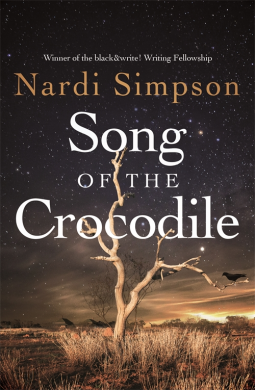

The implication is that it is still observed. It doesn’t, though, seem to get much publicity. I could research this, but so could you if you are interested! Meanwhile, I plan to use this post to share some tree quotes from Australian novels, and a couple of tree-inspired covers, as my little tribute to National Tree Day.

My first quote is one I’ve shared before, because it’s my first memory of a tree playing a significant role in a novel. I’m referring to Ethel Turner’s children’s book, Seven little Australians (1894), and the death of our beloved Judy:

There was a tree falling, one of the great, gaunt, naked things that had been ringbarked long ago. All day it had swayed to and fro, rotten through and through; now there came up across the plain a puff of wind, and down it went before it. One wild ringing cry Judy gave, then she leaped across the ground, her arms outstretched to the little lad running with laughing eyes and lips straight to death.

This is realism. The tree has an important role to play in the plot. Another memorable novel featuring trees is Murray Bail’s Eucalyptus (1998). There is a narrative, of course, but it is framed around multiple species of gum trees, and opens with this:

We could begin with desertorum, common name hooked mallee … and anyway, the very word, desert-or-um, harks back to a stale version of the national landscape and from there in a more or less straight line onto the national character, all those linings of the soul and the larynx, which have their origin in the bush, so it is said, the poetic virtues (can you believe it?) of being belted about by droughts, bushfires, smelly sheep and so on; and let’s not forget the isolation …

As you can tell from the tone, the trees – although very real right down to their botanic descriptions – also set the novel’s tone and have something to say about Australian life and character.

More recent is Madelaine Dickie’s Red can origami (2019, my review). It is set in the Kimberley, but here is a description of a boab tree in Perth, a place where they don’t belong. It symbolises displacement:

The boab’s bark is cracked, its leaves are withered, and its roots strain from the soil, as if it’s planning on splitting town, hitching north.

There are more, but I’ll end with a writer who is loved for his landscape descriptions, Robbie Arnott. It’s hard to choose, but I’m going to use the one I used in my review of his novel, Limberlost, because it is a beautiful example of the landscape mirroring the emotions of the character moving through it. It occurs after a beautiful lovemaking scene:

Afterwards he’d driven them across the plateau through white-fingered fog, through ghostly stands of cider gums, through thick-needled pencil pines, through plains of button grass and tarns, through old rock and fresh lichen, until the road twisted and dived into a golden valley. Here at winter’s end, thousands of wattles had unfurled their gaudy colours. As they descended from the heights their vision was swarmed by the yellow fuzz. Every slope, every scree, every patch of forest, every glimpse through every window was a scene of flowering gold.

The book cover for this novel depicts what I assume is a stylised image of a Huon Pine with a boat, made by the protagonist using this wood.

Trees – or parts of trees, like branches or bark – often feature on book covers, because trees evoke so much in our consciousness. I guess they are easy to stimulate emotions in readers. They can be majestic and grand, or stark and threatening, or soft and sheltering – and suggest the associated feelings.

However, in doing a little research for this post, I stumbled across an old discussion about trees on book covers for crime novels. One was a 2007 blog post titled “Fright time in the forest”. The post broke down the four ways trees had been used on crime novel covers. There are those

- used “more or less anthropomorphically–that is, as stand-ins for human-like monsters”

- used “to establish a sense of desolation and bleakness, or mystery”

- ominous-looking tree fronts, “on which the bark-encased stars loom belligerently overhead like villains preparing to fall upon and do violence to their victims”

- used to “convey a mysterious atmosphere” through effects like fog, snow, a nighttime sky.

Some of these overlap, I think, but I love the blogger’s conclusion, which suggests that

the designers of crime novels–like the storytellers who wanted to warn children off from wandering into the deep woods–have sought to associate trees with danger, disorientation, and despondency, all in the interests of book sales. One wonders whether this is healthy for the future of forests, a rapidly dwindling resource–or even healthy for the future of mankind, which might also become a dwindling resource.

I wonder whether book cover designers ever think of their larger responsibilities (besides garnering sales, I mean)!

I have strayed from where I started, which was to pay tribute to trees and share some favourite covers. However, this little discussion, which was picked up by England’s The Guardian was too interesting to ignore.

Any thoughts on trees in novels or on covers?