Mostly for the Year Clubs, I read an Australian short story, usually from one of my anthologies. However, for 1925, I couldn’t find anything in my anthologies, so turned to other newspaper-based sources, including Trove, but I mainly found romances or works that were difficult to access. And then, out of the blue, I found something rather intriguing, a story titled “The examination”. It was written by a Russian woman named Teffi, translated into English by J.A. Brimstone, and published in The Australian Worker, an Australian Workers’ Union newspaper, on 25 November 1925. I don’t know when it was originally written, nor have I been able to found out who J.A. Brimstone was.

Who is Teffi?

The Australian Worker ascribes the story to N. Teffi. This nomenclature is interesting. My research suggests that Teffi, not N. Teffi, was the pen name of Nadezhda Lokhvitskaya (1872-1952). Wikipedia gives her pen name as Teffi, but its article on her is titled Nadezhda Teffi. Curiously, the article’s history page includes a comment from a Wikipedian, dated 11 June 2014, that “Her pen name is only Teffi, not Nadezhda Teffi”. This Wikipedian “moved” the article (Wikipedia-speak for changing titles) to “Teffi”, but it was later moved back to “Nadezhda Teffi”. Seems to me it should be under “Nadezhda Lokhvitskaya” or “Teffi”. But, let’s not get bogged down. There’s probably more I don’t know about how she used her name over time.

The more interesting thing is who she was. Wikipedia provides what looks like a fair introduction to her life, so I won’t repeat all that here. Essentially, it says she was a Russian humorist writer who could be both serious and satirical, but whose gift for humour was “considered anomalous for a woman of her time”. However, she proved them wrong, “skyrocketing to fame throughout Russia with her satirical writings, so much so that she had candies and perfume named after her”.

Literary scholar Maria Bloshteyn, writing in the LA Review of Books in 2016, would agree. She starts her piece by describing Teffi as “once a Russian literary superstar”, and says that “Nadezhda Lokhvitskaya claimed that she took the comic-sounding and intentionally androgynous nom de plume for good luck”. Bloshteyn writes:

She began to publish in her early 30s and tried her hand in various genres, but it was her short stories, with their keen and hilarious observations of contemporary society, that were read by everyone from washerwomen to students to top government officials. They won her literary success on a scale unprecedented in pre-Revolutionary Russia.

My short story, however, was written post-Revolution, given we are talking 1925. But, I’m jumping ahead. Tsar Nicholas II was a big fan, Bloshteyn says, as was Vladimir Lenin “with whom she worked in 1905 at the short-lived New Life [Novaia Zhizn’] newspaper”. She left Russia in 1919, during the “Red Terror” when things started to turn sour. Her popularity continued in the émigré world. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, her books were read again and “celebrated as recovered gems of Russian humor”.

This potted history sounds very positive, but Bloshteyn explains that there was also darkness in her life, including the death of her loved father when she was young, difficult relationships with siblings, a failed marriage, mental health problems, and more. Also, “she became a victim of her immensely successful but severely confining brand”, meaning editors and readers “only wanted the Teffi they knew” and, worse, “they perceived all of her stories as funny, even when they were clearly tragic”. How frustrating that would be, eh?

She was inspired by – and has been likened to – Chekhov. Bloshteyn says:

Her appreciation of the absurd, of the comic minutiae of life, helps set off the darker or more transcendent aspects of our existence, but her main focus, in the tradition of the great 19th-century Russian writers, was always human nature itself: what makes us tick and why.

I’ll leave her biography here, but if you are interested, start at Wikipedia, and go from there.

“The examination”

“The examination” tells the story of a young girl, Manichka Kooksina, who is sitting for her end-of-year exams which will decide whether she moves on to the next grade. Important things ride on passing them, including staying with her friend Liza who has already passed and getting the new bike her aunt promised her if she passed. However, instead of knuckling down to study she fritters her time, trying on a new dress, reading, and finally filling her notebooks with a prayer “Lord, Help”, believing that if she writes it hundreds or thousands of times she will pass. Needless to say, she does not do well.

The story is beautifully told from her perspective, with much humour for the reader as she flounders her way through preparation and the exam itself. She feels persecuted, an animal being tortured, and resorts to the absurd solution of writing lines, while her nervous peers have at least tried. I wondered why this particular story of hers was chosen by The Australian Worker. Was it the only one available to them in English? Did the examination theme feel universally relevant? According to Bloshteyn, Teffi said that “even the funniest of her stories were small tragedies given a humorous spin”. This is certainly a “small tragedy” for the – hmm, foolish, procrastinating, but believable – Manichka.

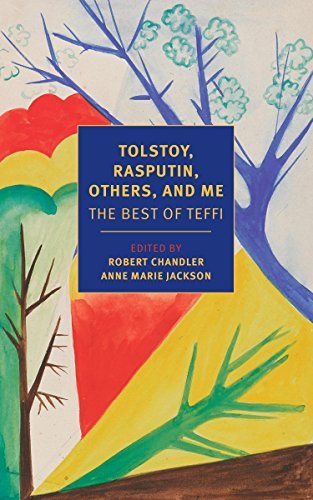

Bloshteyn’s essay is primarily a review of two books that had been recently published, Tolstoy, Rasputin, others, and me: The Best of Teffi and Memories: From Moscow to the Black Sea. The former includes sketches and some of her “best loved short stories”. GoodReads says of it that “in the 1920s and 30s, she wrote some of her finest stories in exile in Paris … In this selection of her best autobiographical stories, she covers a wide range of subjects, from family life to revolution and emigration, writers and writing”. I don’t know whether “The examination” is one of them, but Bloshteyn writes, of the child-themed stories she mentions, that all “show children in the process of getting to know the world around them and finding the means to cope with it”. Manichka, although showing some resourcefulness, has a way to go.

I was thrilled to find this little treasure in Trove, and will try to read more Teffi. Has anyone else read her?

* Read for the 1925 reading week run by Karen (Kaggsy’s Bookish Ramblings) and Simon (Stuck in a Book).

N. Teffi

“The examination” [Accessed: 21 October 2025]

in The Australian Worker, 25 November 1925

I’ve said before that I’m surprised by how many takes there can be on World War II, and on the Holocaust, in particular – and once again I’m here with another such story, Emuna Elon’s House on endless waters. I hadn’t heard of Elon before but,

I’ve said before that I’m surprised by how many takes there can be on World War II, and on the Holocaust, in particular – and once again I’m here with another such story, Emuna Elon’s House on endless waters. I hadn’t heard of Elon before but,

One of my rules of reading is that when I have finished a book I go back and read the first chapter (or so) and any epigraphs the author may have included. These can often provide a real clue to meaning. This rule certainly applies to my latest read,

One of my rules of reading is that when I have finished a book I go back and read the first chapter (or so) and any epigraphs the author may have included. These can often provide a real clue to meaning. This rule certainly applies to my latest read,  I bought Shokoofeh Azar’s novel The enlightenment of the greengage tree when it was longlisted for the 2018 Stella Prize, for which it was also shortlisted. However, it was its shortlisting this year for the International Booker Prize that prompted me to finally take it off the TBR pile.

I bought Shokoofeh Azar’s novel The enlightenment of the greengage tree when it was longlisted for the 2018 Stella Prize, for which it was also shortlisted. However, it was its shortlisting this year for the International Booker Prize that prompted me to finally take it off the TBR pile. Shokoofeh Azar

Shokoofeh Azar All these books have won major awards and/or been bestsellers (by Australian terms, anyhow). None are simple or easy books, and none present Australia at its best. In this sense they represent “true” literature that grapples with real issues, and clearly meet the goal of revealing ‘Contemporary Australia’ (in all its messiness.) Clearly, they appreciate that historical novels also say something about “contemporary” Australia. It’s encouraging that the program is still going, and is supported, it seems, by quality launch events. So many visionary programs like this seem to flounder.

All these books have won major awards and/or been bestsellers (by Australian terms, anyhow). None are simple or easy books, and none present Australia at its best. In this sense they represent “true” literature that grapples with real issues, and clearly meet the goal of revealing ‘Contemporary Australia’ (in all its messiness.) Clearly, they appreciate that historical novels also say something about “contemporary” Australia. It’s encouraging that the program is still going, and is supported, it seems, by quality launch events. So many visionary programs like this seem to flounder.