Susan Wyndham with Julieanne Lamond

The program described the session as follows:

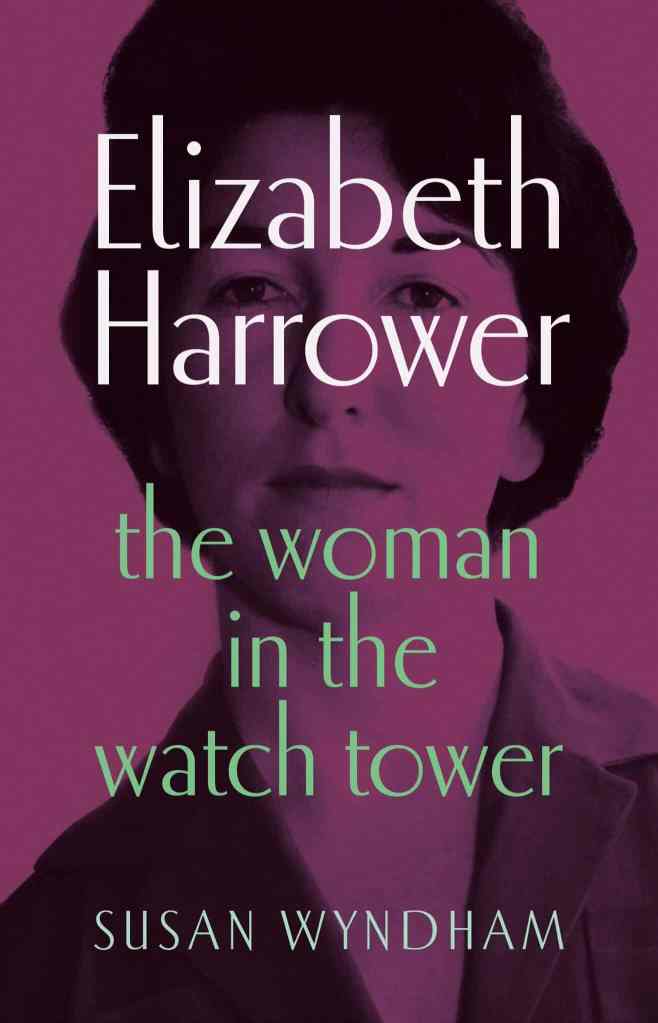

A literary biography can be a truly fascinating exploration of the life of an author beyond their pages, and so it is with Susan Wyndham’s Elizabeth Harrower: The woman in the watch tower. Harrower wrote some of the most original and highly regarded psychological fiction of the twentieth century. Then she abruptly stopped writing in the 1970s and became one of the most puzzling mysteries of Australian literature. Why didn’t she continue? What part did her circle of famous friends play? Why is her work now enjoying a remarkable renaissance? Join ANU Associate Professor of English, Julieanne Lamond and writer, journalist and former literary editor of The Sydney Morning Herald, Susan Wyndham for this conversation.

Julieanne Lamond, who teaches English at the ANU, introduced Susan Wyndham, journalist, literary editor and author, most recently, of the biography of Elizabeth Harrower: The woman in the watch tower.

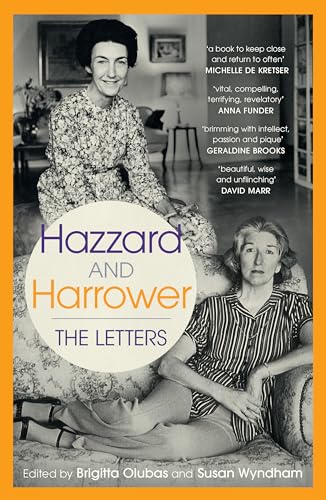

There wasn’t a lot that was new for me in this session, because I’ve read a good proportion of her letters with Hazzard (not reviewed yet, because not finished) and Helen Trinca’s Harrower biography (my review). But I’ll document my notes for the record – and, reiteration always helps the memory.

Julieanne started with the obvious question to a biographer …

Why write about Elizabeth Harrower?

Susan first heard of Harrower when she won the Patrick White Award in 1996, but didn’t read her books until 2014 when Text was publishing her novels, including talking Harrower into publishing the shelved novel, In certain circles. This was Susan’s impetus to read and interview Harrower. She found her novels vivid, and was stunned by their power. But, over the years, she had many questions that were left hanging.

After Harrower’s death in 2020, her papers became available. Susan also knew that Brigitta Olubas was working on Shirley Hazzard with whom Harrower had a long and deep correspondence, so her interest was sealed.

On her childhood – and its influence on her writing

Harrower, like Trinca, found many holes in Harrower’s story. She was able to fill some through her research, but not necessarily fully. Harrower painted over her origins, saying she was born in Sydney not Newcastle. She always called herself a “divorced child” and said she “never saw happy marriage” when she was young.

Susan jokingly said that if you are writing a biography, pray for a messy family, because stories about divorces, crime, deaths will be documented in government and other records. After her parents’ divorce when she was 4, Harrower lived with her grandmother, which inspired her novel The long prospect (my review). She was an only child, and solitary, though Susan did track down a childhood Newcastle friend. Overall, she had to make her own way through her childhood – and was a great reader.

Her childhood was divided in two parts – up to 12 in Newcastle, then she joined her mother in Sydney, with her mother’s new partner (and perhaps husband). This “stepfather”, R.H. Kempley was the model for Felix in The watchtower (my review), a book which still feels modern, and certainly relevant.

Julieanne segued into asking about Felix and Harrower’s intense psychological portrait of a coercive controlling relationship. Susan didn’t want to take away from Harrower’s creativity, because she was a great observer of people – hence the biography’s title. Indeed, Harrower said, “I wouldn’t have survived if I experienced everything in my novels”.

Susan described R.H. Kempley, whose name she tracked down through a brief mention she found in Trove about Harrower’s parents expecting her arrival back from England with her friend (and cousin) Margaret Dick. Her research into him found much evidence of crime – selling moonshine and blackmarket alcohol, debtor’s courts, and the like. Harrower felt shame, but he was a gift to her as a writer if not as a child.

Harrower, Susan believes, ran away from domesticity, determined to be independent and not controlled by anyone, but money was always a problem.

On whether she saw herself as a feminist

Harrower resisted the term, didn’t connect with it, but the way she wrote and lived her life showed she “knew it all”. Anne Summers included her in Damned whores and God’s police in her chapter on women writers.

On the shape of her career or, why she didn’t become the writer she set out to be

Those of you who know Harrower’s trajectory will know that she did not publish a novel after The watchtower in 1966, until Text Publishing republished her novels in the early-2010s, and talked her into publishing her unpublished manuscript, In certain circles (2014, my review).

There is no easy answer to this question said Susan (as Trinca also explored). Her novels were well received critically, and after The watchtower, which was published in Australia, everyone was waiting for her next. She received a Commonwealth grant, but was uncomfortable about it. She always said she wrote under difficult circumstances. She did write short stories and plays, but Susan thinks she’d lost her drive. She was trying something different, but it didn’t “come from her heart or her guts in the same way” as the four published novels had.

She was disappointed not to win the Miles Franklin Award for The watchtower. Also, her mother died, which paralysed her emotionally. She never got her momentum back. She became emotionally involved in politics. Having always been a great Labor supporter, she threw herself into supporting the party with Whitlam’s win in 1972. She was visiting Christina Stead in 1975, when the dismissal happened and was outside Parliament House when Whitlam made his speech. Also, she was enjoying her social life.

On seeing other writers through the lens of Harrower

However, although she only published one novel in Australia after her return from London in the 1960s, she moved in literary circles. She was not a big personality, but people loved her parties and she was a devoted, loyal, “almost too attentive” friend.

This is where her letters with Shirley Hazzard – from the 1960s to 2008 – come in, with their coverage of Harrower’s significant role in caring for Hazzard’s mother Kit. It took up a lot of time. She was willing, but resentment did build up. The supportive picture we see in her letters to Hazzard, is not the same one seen in her letters to and conversations with others. She didn’t like conflict, but she didn’t like feeling put upon, either. This – along with the fact that she was a giver but didn’t like accepting generosity – was probably behind the break in the friendship that occurred during her visit to Hazzard and her husband on Capri.

Harrower had many writer friends, including, significantly Patrick White, Kylie Tennant and Judah Waten. There was some discussion about these, particularly about White who was “a bit of a big brother figure”. They talked on the phone every Sunday, went to shows together, shared an intellectual life together. During the Q&A, Susan added that they had arguments, and shouted at each other, but, although he hurt her at times, she was a peacemaker. It was a genuine friendship.

On Susan’s research, including her Fellowship at the NLA

The National Library not only has Harrower’s papers but those of many in her circle, which provided a wonderful mosaic that offered different ways of looking at Harrower. Cross-referencing enabled her to solve mysteries, such as who she went on a cruise with – a cruise to Japan from which she jumped ship in Brisbane. (Harrower doesn’t provide the person’s name in her Hazzard letters, but did elsewhere. She was “annoyingly discreet”, and didn’t always name people. In this case, she named “Kylie” in a letter to Christina. Her relationship with Kylie was long and fraught.)

Unfortunately, like many writers, Harrower also destroyed papers, such as diaries and letters to her mother.

Q&A

On her relationship with readers: back in the 1950s and 60s, there were no public events, but she was reviewed and did have champions in the literary world. However, after being republished in the 2010s, she did her first ever public events, always with her publisher Michael Heyward, and she loved it. Her responses were always “beautifully formed, but left a whole lot out”. The 2017 Adelaide Writers Week was dedicated to her. She said there, that the greatest human quality was kindness.

On not continuing to write: Susan reiterated some of what she’d said during the conversation, but added that caring for Kit was probably also an issue. Susan thinks nothing was going to get her to write.

On which book to start reading Harrower: Probably The watchtower (her fourth novel), and then The long prospect, which is exactly my order! But Susan is becoming more fond of The Catherine wheel, the only one set in London

I enjoyed the session, though more on biography-writing itself would have been interesting. I could have asked a question, I guess!

Canberra Writers Festival, 2025

Finding Elizabeth Harrower

Saturday 25 October 2025, 1-1:30pm