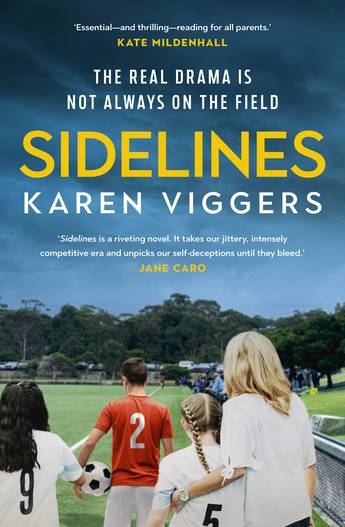

I don’t usually start a book review by relating its content to my own experience, but local author Karen Viggers’ latest novel Sidelines invites exactly this. Sidelines is about children’s sport and what happens when the competitiveness gets out of hand. It was largely inspired by Viggers’ own experience as the mother of sporty children, and by an ugly parental brawl at a children’s football match that happened during those years.

My children’s sport experience was blissfully different. Our son played cricket, and his coach’s last name was McPhun – I kid you not. He was the perfect children’s sport coach. His focus was on “phun” and teamwork. He encouraged those kids, was fair about opportunity, did not favour his own son, and we parents had the best time. I loved seeing the enthusiasm with which the kids played, and their resilience when they were out for a duck, despite having gone in to bat with dreams of sixes and high scores. You won’t be surprised, perhaps, to hear that our kids were not in the elite division, but this should not make any difference. Unfortunately, however, it probably does.

So, Sidelines. As Viggers explained at the meet-the-author event I attended – and as is obvious if you read it – her novel has a structure rather like Christos Tsiolkas’ The slap*. This means that the novel’s story or plot is progressed through a sequence of different, third person, points of view encompassing the parents and children involved in the sport. Sidelines is a little different though because in Tsiolkas’ book, the slap occurs in the first chapter and we then watch the fall-out from that action. Viggers’ novel commences with a prologue describing an ambulance arriving at a sports ground where a badly injured child is lying far from the goal-posts. “What the hell happened here?” We then flash back to nine months earlier and, through those sequential voices, we work our way towards what had happened and why.

“It’s not meant to be fun” (a football father)

The novel focuses on two families – the well-to-do Jonica, Ben, and their 13-year-old twins, Alex and Audrey; and the Greek-Australian working class family of Carmen, Ilya, and their daughter Katerina. Into this mix comes Griffin and his single-parent Dad, Lang. Griffin is a natural, and his appearance upsets the team’s sporting and interpersonal dynamics. The characters telling the story are Jonica, Carmen, Audrey, Katerina, Ben, and finally, Griffin. For each voice, there is a thematic word or phrase that provides insight into, and commentary on, that character.

The first voice, Jonica’s, initially made me feel I was reading one of those stories about a dysfunctional family. You know, the well-to-do family with the successful, professional, and controlling husband, the privileged children, and the wife and mother caught somewhere in the middle. And there is some of this aspect in the novel, because, as becomes clear, part of the story Viggers is telling is one of class. So, in Jonica’s story we see the tropes of her class. Everything is laid on in a material sense, but the two females, in particular, aren’t happy. Jonica, like her husband, is a lawyer, but she is frustrated about not working. Ben, you see, “likes having her at home”, and insists she is needed to look after the children. He will “support her” (and the family) while she supports the children. There’s an irony in this word, “support”, which is Jonica’s theme, because, as Viggers said during the author talk, there’s a fine line between “support” and “pressure”. Audrey certainly feels more pressure than support.

The next voice is that of the other mother, Carmen, whose daughter, Katerina, like Audrey, is trying out for a place in the boy’s team where, as Ben had told Jonica, girls will learn “speed and aggression”. While Jonica tries, unsuccessfully, to resist her husband’s pressure to push the children, Carmen is more like Ben. She wants her daughter to achieve where she had failed, and she will manipulate and kowtow as much as is necessary to ensure this happens. Her theme or motif is “goal poacher”, the one who “attempts to shoot goals from loose balls … and uses other non-traditional ways of scoring”. Perfect for the resourceful Carmen.

And so the novel progresses through to Audrey’s and Katerina’s voices, where we see the pressures that their parents don’t. These girls do want to play well, but they also want other things in their lives. They are teens, for heaven’s sake! And Viggers’ rendition of them convinced me.

The penultimate voice is Ben’s, and here, in particular, is where Viggers’ choice of a multi-voice structure shines, because, while he’s still unlikable, we also see his point of view. Ben is the alpha male, no doubt about it, but he loves his family and he’s not so tuned out that he doesn’t sense something is wrong with Audrey in time to take critical action. This is the value of reading, being able to see a situation from another point of view. We don’t have to agree with Ben – I’m sure few of us do – but we can see where he’s coming from and that he’s human. This awareness can be achieved with third person voices, of course, but Viggers has effectively used first person voice here to directly confront readers with her protagonists’ thoughts.

By the end of the novel I was impressed by the careful and sophisticated way in which Viggers had developed and explored her main idea, which is to encourage us to think about our attitudes to and behaviour around competitive children’s sport. She offers no easy solutions. This is not a didactic book. There are many points left open for readers to think about. Can you play for fun, for example, and what does that look like?

In the above-linked interview with Viggers, she said she has realised that she is an issues-based writer. This is exactly what I thought as I started reading Sidelines. On the surface, it departs from her previous, environment-themed novels but, in fact, like those novels, it takes an issue Viggers cares about and explores it through characters who are real on the page. I enjoyed the read, but more than that, I hope it gets read and talked about in places where it matters.

* Interestingly, another Tsiolkas book, Barracuda (my post), starts with elite children’s sport, but while class is also an element, it takes a long view of what happens when things don’t go to plan.

Karen Viggers

Sidelines

Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin, 2024

343pp.

ISBN: 9781761470714