A preamble

The Canberra Writers Festival is back in 2024, with last year’s wonderful Artistic Director, the writer and critic Beejay Silcox. The Festival’s theme continues to be “Power Politics Passion”, although that tagline is not quite so visible on the website. This is good – to my mind at least. Last year, under Beejay Silcox, there was a clear shift in programming away from the heavy political flavour we’d been experiencing to something more diverse and literary. That must have been successful, as this year’s programming has continued this trend, so it has lot to offer the likes of me! So much so that more difficult decisions than usual had to be made about what to attend. Wah! But, that’s better than struggling to find appealing sessions.

The most interesting man in OzLit

Before I tell you WHO this “most interesting man in OzLit” is, I must share that attending this session involved one of those difficult decisions, because overlapping this session was one titled “The power of quiet”. It featured Robbie Arnott and Charlotte Wood discussing “their favourite hushed and gentle books, and the art of less is more”. I am a big believer in “less is more” so would love to have attended this session, but “the most interesting man in OzLit” called, and I will be seeing Arnott and Wood in their own dedicated sessions elsewhere in the festival.

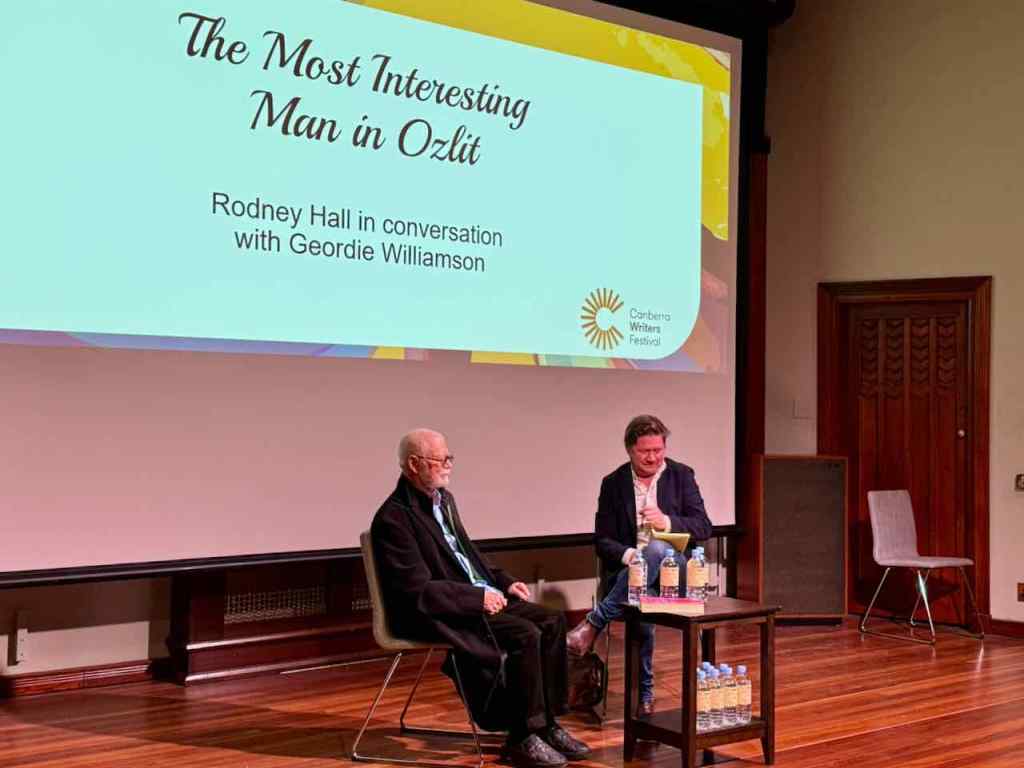

So, who is this “most interesting” man? Well, it’s Rodney Hall. The session was described as follows:

Rodney Hall has stories to tell: he walked across Europe, harboured Salman Rushdie during the fatwa years, and has won the Miles Franklin Literary Award – twice. At 89, Rodney has a new novel to share, Vortex, and it just might be his best. Join Rodney and his devoted publisher, Geordie Williamson, as they discuss his magnificent life on and off the page.

To my shame, I have only read three of Hall’s novels, Just relations, The day we had Hitler home, and, since blogging, A stolen season (my review), but – here comes the reader’s plaint – I have always intended to read more. He is one of those writers who, despite a significant body of work, seems to be under the radar, and I really wanted to hear him in person.

The conversation

There was something different about the audience for this session – at least in my experience of festival attendance. First, over 50% were male, and the median age seemed higher than usual too. This clearly says something about the subject of the session.

Geordie commenced by suggesting that with the small audience (though it was larger than the afternoon session I attended) this could be a bespoke session. And, I think this is how it turned out because it seemed to flow naturally in reaction to Hall’s “stories”. Geordie clearly had ideas about what they’d explore, but he handled it with lovely fluidity. Before introducing “the most interesting man”, Geordie apologised to Peter Goldsworthy, another “interesting man”, who was in the audience!

Geordie then did the usual author introduction, listing Hall’s output (which includes 14 novels, poetry, short fiction, two biographies, political polemics, plays, and librettos), his literary achievements (award wins and short listings), literary roles (including on the Australia Council) and political activism (in issues like the Republican movement and Indigenous Land Rights). Rodney – I have been using first names for author events for a while now so will continue – has been a very busy man.

I’m not going to do my more usual blow-by-blow account of this discussion because it seemed to revolve around a couple of main themes. In fact, I’m going to suggest that the way the session went might mirror somewhat Hall’s latest novel, Vortex, which he described as having the structure of a rondo, meaning it keeps returning to the same statement.

The point that kept recurring through the conversation was that Hall sees himself as a classicist. For him, this means that structure is fundamental to what he does, and this structure tends to be musically based. That is, he thinks in musical forms, and these provide the spine for his work. (Music, he said later, speaks to the divine, which doesn’t mean “God” so much as something more generally spiritual, inspirational.) Interestingly, and perhaps contradictorily – on the surface at least – he described himself as a “pantser” not a “planner”, though he didn’t use such informal terms. He spoke, for example, about his good friend Murray Bail who plans his work out meticulously, while Rodney described his writing projects as putting himself “in the way of a blundering machine”. He starts from some sort of interest and sees where it goes, which is sometimes nowhere.

It might be for this reason – for this “classicist”, structural, approach to his work – that Beejay Silcox recently told Rodney that he was “not political but ethical”.

And now, because I have departed from the structure of the conversation, I have to work out where to go next! But, let me see … Geordie started by trying obtain some sort of “origin myth” from Rodney, who had once told Geordie that his memoir was “rubbish”. But we didn’t get there in any straightforward way.

Responding to the idea of an “origin myth” and Geordie’s asking him to talk about his troublemaker mother and their experience of the blitz, Rodney shared a little of his background but then said that he is “deeply suspicious of the notion of stories” because they are “never true”. They leave out “the other bits”, the real or, I guess, true bits.

He then talked a bit about his approach to writing. He doesn’t, for example, model his books on people he knows. This he feels is an intrusion on their privacy. Later, he talked about Vortex, which was inspired by some portraits he’d written of real people. They were in a book that was nearly published but he pulled it. Then, on reflection – I think I got this right – he felt he could pull out the “material” from these portraits, and us it in another work, without forensically analysing his friends.

Geordie reflected that what Rodney writes is the opposite of the current flavour of the month, autofiction, with which Rodney agreed. His classicism he said is out of step with his colleagues – whom he, nevertheless, likes and admires. They are interested in more personalised expression, because people “want the dirt of what you are yourself”. He, on the other hand, doesn’t seem to write what people want to read. Geordie commented on the sort of experimentation that Rodney likes to do, and asked whether he was conscious that people weren’t reading him!

It was probably around now that we got some of the aforementioned “origin story”. Rodney, who arrived in Australia (Brisbane) postwar, had to leave school at 16. So, unlike his peers, he never did “literary studies” but read what caught his attention. Caribbean literature, for example. He didn’t read Bleak house but did read Wilson Harris’ Palace of the peacock.

So, wondered Geordie, is autodidacticism the key to understanding him as a writer? And the conversation moved on to his formative influences, which included Caribbean literature; the 18th century Italian philosopher Giambattista Vico (and his book The New Science which teased out the differences between “myths” and “legends”); and Robert Graves. Each of these influences were formative in different ways, but Rodney spoke most about Graves, and a two-hour conversation he had had with him when he was a young man.

In fact, Robert Graves came up several times throughout the conversation, but I’ll try to bring it all together here. In 2011 (I think), Rodney lost his house in a fire – and with it went 30 to 40 unfinished novels, and his correspondence with people like Robert Graves and Judith Wright. (As a librarian-archivist I am aghast at what the literary community – let alone Rodney himself – lost through this.)

Geordie asked Rodney to name the book that was dearest to him, that he would save if he could save only one, and Rodney replied Just relations because in it he found what Robert Graves said was there to find. I take this to mean a sort of essence of things. (My words, not his.) He had a 2-hour meeting with Graves – after landing, uninvited, on his doorstep in Mallorca, and nearly being sent away by his wife. It sounds like Graves was generous with his advice. He talked to Rodney about writing being about “what don’t you know that you need to know”, about tapping into the “collective unconscious”, about finding the “inexplicable thing”. Graves recommended, when writing historical fiction, to write first (to find out what you need to know) and research later (to make sure people believe you). Graves, said Rodney, “was my university”.

There was much more to this session, more anecdotes – including a lovely one about labyrinths – but I’ll conclude with a few things about Vortex. It is set in 1954, the year of the Queen’s first visit, the Petrov scandal, Menzies (who had many years besides this one!) The underlying question for Rodney is that “we don’t know when the things that affect our lives are hatched”. You can call him a conspiracy theorist he said, because he believes there usually is one.

Geordie, who published the novel, believes Vortex is one of great contemporary Australian novels. It offers a long view. It is bookended by Royal Visits (being published just as we’ve just had another), and the nuclear issue is being raised again. Not much has changed, in other words – though maybe one thing has. In a discussion about students being radicalised in the late 1960s and early 1970s by the Vietnam War, and whether the same was happening now with Gaza and the October 7 attack, Rodney wasn’t sure. He said, back then, we knew what was being done in our name, but the news is so poor now we cannot be so sure of what we know. He also commented on the fact that no-one asks “why” things happen. When young First Nations people create havoc in Darwin, for example, they are locked up. No-one asks why they are angry.

Geordie shared an anecdote about Rodney pitching Vortex to him as a set of individual chapters that could be infinitely shuffle-able! But Geordie, self-deprecatingly calling himself “an agent of the industrialisation of art” looked horrified, so Rodney changed it!

There was more, including a short Q&A but it essentially built on what we’d heard rather than introducing anything new so, this post being long enough as it is, I’ll leave it here. I am so glad to have seen Rodney Hall in person. He is indeed most interesting!

Canberra Writers Festival, 2024

The most interesting man in OzLit

Friday 25 October 2024, 10:30-11:30am