I wonder why I didn’t read this book when it was published about 10 years ago? In the 1960s, when I was in my teens, I read poems like Kath Walker’s (later Oodgeroo Noonuccal) We are going; in the 1970s when I was at university it was more academic works such as the white anthropologist CD Rowley’s The destruction of Aboriginal society; and in the 1980s it was Sally Morgan’s My place. Later, in the 2000s it was Leah Purcell’s Black chicks talking. These and other books have both moved and educated me with their portrayals of the richness of indigenous culture in Australia and of the dispossession of its people. And yet, in the 1990s, I missed this treasure (written in collaboration with Meme McDonald).

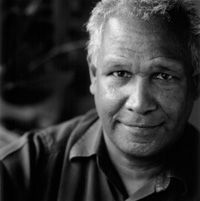

It is a treasure because, although Boori Pryor and his family have experienced huge tragedy and significant intimidation, he is able to preach reconciliation and mutual respect. Classed as a biography and often promoted as a book for young adults – indeed it was shortlisted in the Children’s Book Council of Australia awards – the book has a much wider ambit. While we learn a lot about Boori’s life, that is not his purpose in writing the book. His purpose is to encourage white society to understand – really understand – where Aboriginal people are coming from, and particularly the far-reaching implications for them of Invasion Day, and to encourage Aboriginal people to trust in their roots and to recognise the importance of their stories, their cultural tradition, to their individual survival as well as to the survival of their people.

Much of the book deals with his work in schools where he aims to encourage students to develop an understanding of and respect for Aboriginal people and for the land. He believes that all people need to have and know their “place”: the first chapter is subtitled “To be happy about yourself you have to be happy about the place you live in”. He talks about the thoughtless and insulting things young people say to him and how he handles it. He says

You have to be the water that puts out the fire. If you fight fire with fire, everything burns.

He seems to be able to “maintain the rage” regarding what has been done to his people while at the same time working wisely and calmly to make things better.

Boori says in the book that storytelling is part of who his people are. After reading this book – with its mix of anecdote, metaphor, analogy and humour – I, for one, would not argue with him.

Boori Monty Pryor with Meme McDonald

Maybe tomorrow (1998)