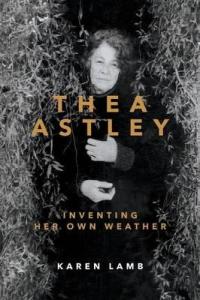

One of the threads that runs through Karen Lamb’s biography, Thea Astley: Inventing her own weather, is Astley’s ongoing frustration about her work not being appreciated or recognised. On the face of it, this seems neurotic or, perhaps, paranoid. After all, she was the first writer to win the Miles Franklin Award four times, a feat only equalled to date by Tim Winton, and she won pretty well every other major Australian literary award including the Christina Stead Award for Fiction and The Age Book of the Year Award. Yet, as I have often mentioned on this blog, I would agree that she is under-appreciated. Indeed, winning the Patrick White Award when she was 64 and had published 11 of her 16 books somewhat supports her case. It is awarded to a writer who has been highly creative over a long period but has “not received due recognition”. Lamb quotes her as saying “Ya know what it’s for, it’s for people who fail”! Not quite, if you look at the list of winners, but …

“a writer’s writer”

Why is this? Well, part of it could be gender-based. Astley’s satire and, yes, ferocity were not the fare “expected” of a woman. And part could be because, as author Matthew Condon put it, she’s a “writer’s writer”. This means, I’d say, that she doesn’t pull any punches to prettify her feelings and attitudes, her language is complex and imagistic, her works don’t necessarily neatly fit traditional forms, and she doesn’t dumb down. (It helps to have a dictionary nearby when you read her). But, she is so worth the effort, because she can move you to laughter or tears or just plain anger and shock with her way of expressing the world she saw. You may have heard her four ages of women – “bimbo, breeder, baby-sitter, burden” (Coda) – but what about her description of time as “the great heel”?

“My novels are 90% ME”

Let’s now, though, get to the biography. Why do we read author biographies? Why not just read – and re-read – more of their works? Is it simply a voyeuristic activity or can biographies add something of value to our understanding? And if the latter, what sort of understanding? Is it valid to try to understand an author’s works though his or her life, or, vice versa, to understand the life through the works*? These can be minefields for literary biographers, but they’re minefields Lamb has stepped lightly across. Astley’s statement that “My novels are 90% ME” helped, yet the question is still valid.

How has Lamb done it? For a start, she doesn’t attempt any pop psychology. She presents the story of Astley’s life, noting points of interest, of stress and tension – such as her very strict Catholic upbringing – but she doesn’t labour the point. She lets the reader make most of the assumptions or connections. Similarly, she situates the works in Astley’s time-line, describing what was going on at the time and drawing out themes and concerns – such as those of the outcast and misfit – that recur in her novels. She tracks changes in Astley’s thinking, such as her complex attitude to gender and feminism, through both her life and her work. Astley’s early works from the 1950s and 60s, for example, were mostly written from a male or “neuter” perspective, but later in her career, as times changed, she shifted to a female point of view.

Lamb tells the story, like most biographies, in a generally chronological manner. The book is logically organised into four parts – youth, early career, middle career, and later career – with gorgeously evocative chapter titles most of which come from Thea’s own words. Chapter 2, for example, is “Suspected of reading” from Beachmasters, and Chapter 9’s “I merely crave an intelligent buddy” is from a letter. Underpinning this chronology are recurring themes, including her anxieties about critical recognition and her ongoing battle with publishers to get a fair deal for literary writing; her awareness of her “difficult” style; her persistent focus on and interest in outsiders and misfits, gender, and male-female relationships; her smoking; her long, complicated but loving marriage; and what Lamb describes as her “twin modes of existence”, that is, her adoption of an insider-outsider role or persona. As the book progresses, all these appear and reappear, creating a coherent picture of Astley as a complex, idiosyncratic, frequently funny and often irascible, but oh so very human person.

I was, naturally, interested to read about Astley’s life. I loved that Lamb confirmed the Astley I thought I knew, while filling in the gaps and the backstory that helped me understand her better. I was thrilled, for example, to discover that Astley loved Gerard Manley Hopkins. That made complete sense, considering her style, but how I wish my love of Hopkins had the same effect on me! Anyhow, I was also, of course, keen to read about the writing and the publishing, about the works and how they fitted into her life. Lamb met this intelligently, slotting the works into the chronology, and explaining salient points, as relevant, about what inspired them, who edited and published them, what the critical response was, how they relate to her oeuvre, and so on. I’ll be returning to these – via the thorough index – as and when I read and/or re-read her works.

“It can be lonely at the bottom”

So far I have written mostly, as I should, about the biography itself, but, before I finish, I do want to shine a light a little more specifically on Astley and her work. One of the recurrent issues in Lamb’s book is Astley’s ongoing concern, mentioned earlier, regarding her lack of, or mixed, critical reception. Lamb suggests that, partly to defend herself from critics but partly also because it was how she wrote, Astley described herself as “intensely interested in style”, the subtext being that style was more important to her than plot. In this, Lamb suggests, she was like Patrick White and Randolph Stow. She could be hard on herself, saying early in her career that

It’s a fearful thing to have de luxe standards and be limited by technique and self. I know the country I want to explore but I only seem able to chart its coasts.

Yet she didn’t take (negative) criticism well. This is interesting, given she often opened herself up to it. Perhaps it is partly because she didn’t feel understood. It’s difficult to accept criticism when the basis of that criticism misses the mark, as it often did. Astley, for example, experimented with style and form throughout, but not everyone appreciated that. However, it is also very likely that gender played a role. In 1981 she wrote:

Perhaps it is because I am a woman – and no reviewer, especially a male one, can believe for a split infinitive of a second that irony or a sense of comedy or the grotesque in a woman is activated by anything but the nutrients derived from ‘backyard malice’ … the Salem judgement comes into play and the lady writer is more certainly for burning.

The other point I want to make relates to her themes. Lamb argues that Astley consistently explored outsiders and misfits, and ideas about gender, and male-female relationships, particularly in relation to power and responsibility. Her subject matter may have changed from her early treatment of “teachers, small towns and islands”, and then of suburban life, to wider social concerns about justice, development and indigenous dispossession, but her “obsessions” persisted. I think, as does Lamb, that by the end she’d come full circle, but to a more sophisticated expression, from the lonely, isolated teacher in 1958’s A girl with a monkey to a despairing Janet writing for the last reader in 1999’s Drylands. Such an impressive, tightly focused but never boring oeuvre.

I could say the same about this biography. At just over 300 pages (excluding the end-matter), it manages to be both extensive and intensive. It is tightly focused but never feels like a mere recording of facts. It is honest and affectionate but not hagiographic. It portrays that paradox typical of creators, the self-protective writer who lays herself bare. And it demonstrates that Astley’s concerns are as relevant today as they were when she died in 2004. Lamb’s biography goes some way towards according Astley the recognition she wanted and deserved. May it be just the start.

Lisa (ANZLitLovers) would agree.

Karen Lamb

Thea Astley: Inventing her own weather

St Lucia: UQP, 2015

360pp.

ISBN: 9780702253560

(Review copy supplied by UQP)

* Carol Shields’ biography of Jane Austen is an interesting example, because it’s a case of a novelist writing about a novelist about whom little is known. Shields was upfront about using Austen’s work to fill in the gaps. It worked because she was honest about what she was doing.