As I research for my 1924 Monday Musings series, I am coming across articles that don’t neatly fit into 1924-dedicated posts but that I want to document. The most recent one concerned the Lothian Book Publishing Company. It was about a specific initiative, which I will discuss at the end of this post, but I was intrigued to find out more about the publisher itself.

AustLit tells us that, while now an imprint of Hachette Australia, Lothian has a long history, starting well over a century ago, in 1888 in fact, when it was founded by John Inglis Lothian. Then it was a Melbourne-based book distribution company, but it started publishing in December 1905 under John’s son, Thomas Carlyle Lothian. During its first three years, it produced 40 books and four periodicals. AustLit then jumps to the interwar years (the 1920s and 30s) and says that it “was particularly notable” for publishing Australian poets, such as Bernard O’Dowd and John Shaw Neilson. Lothian also represented Penguin Books in Australia until the end of the Second World War. Cecily Close, in her article on Thomas Carlyle in the ADB, provides more information, and adds other authors to their list, like Miles Franklin and Ida Outhwaite.

The company was active, and by 1945, it had offices around Australia and in Auckland, and had literary agents in London and New York. It remained a family-run affair, with Thomas Carlyle Lothian being followed by his son Louis Lothian, and then Louis’ son Peter Lothian.

Austlit says that the company moved into children’s publishing in 1982, which has remained a big part of its activity since. Then the take-overs started. In December 2005, the Time Warner Book Group acquired Lothian and formed the Time Warner Book Group (Australia), with Lothian Books becoming an imprint of Time Warner. Very soon after, in February 2006, Hachette Livre acquired the global Time Warner business, with Lothian Books now becaming an imprint of Hachette Livre Australia. Lothian Books’ CEO Peter Lothian retired in July 2006.

The focus on children’s books has continued with Hachette Australia expanding its children’s publishing, and branding its children’s books with the Lothian imprint. AustLit says that as part of the new arrangement, some adult publishing would continue, as a ’boutique’ list of Australiana titles, both already published and to be commissioned, but I’m not sure that this eventuated, or, if it did, that it lasted. Hachette Australia’s website does not clearly differentiate its imprints.

Lothian stories

It was a story about Lothian that inspired this post, but while researching it, I found another intriguing story, so I’m closing with two little anecdotes about Lothian.

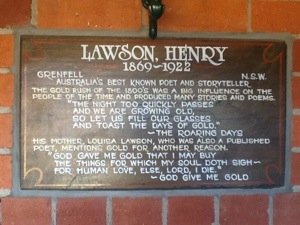

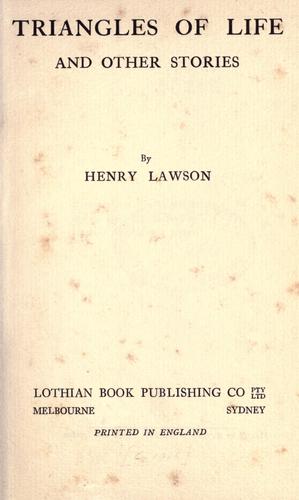

Lothian and Henry Lawson

The State Library of Victoria’s La Trobe Journal carries an article by John Arnold about the relationship between Lothian founder, Thomas, and Henry Lawson. You can read the article yourself as the story is not a short one but, essentially, it started in 1907 when, on a business trip to Sydney, Thomas Lothian signed a contract with Henry Lawson to publish two collections of his writing, one of prose and one poetry. The contract was signed in James Tyrrell’s bookshop in Castlereagh Street, Sydney.

I won’t go into the details but it was a standard Lothian printed contract. The author would receive a 10% royalty for each title. Lawson was to deliver the completed manuscript of both titles to the publisher, two weeks after the signing of the contract, and Lothian was to publish the two books no later than three months from receipt of manuscript. The contract “declared that the author was the proprietor of the copyright of the material proposed to be published and it gave the publisher the world serial, translation and dramatic rights to the material in question”.

This is not what happened, and Arnold writes that “this commercial agreement … was in a short time revised, revised again, then broken, leading to false promises, abuse of copyright, and a falling out between author and publisher. The proposed books were not to appear for six and a half years”.

It was a tortuous process, due largely to Lawson’s “erratic behaviour” but also affected by Lothian’s busy and ambitious workload. Arnold concludes his article with:

Despite his unrewarding and frustrating dealings with Henry Lawson, Lothian was still willing to chip in when the Lawson hat was sent round after the author’s death. In 1928 he became a Life Member of the Footscray-based Henry Lawson Memorial Society, and in 1931, as one of Lawson’s publishers, wrote a one-page testimonial to be read at the society’s annual meeting.

The handsome certificate with which Lothian was presented by the Henry Lawson Society in 1938 stated that Life Membership was awarded for ‘Unselfish and Generous Services rendered to this Society and Australian Literature generally’ …

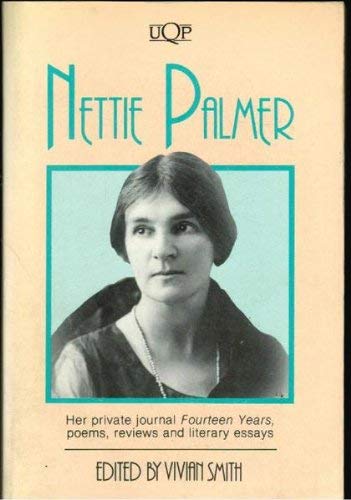

Lothian and Nettie Palmer

Finally we get to the article that inspired this post, the announcement in The Argus of 8 May 1924 that Nettie Palmer had won a “prize of £25 offered by the Lothian Book Publishing Company for the best critical essay dealing with Australian literature since 1900”. Her essay was titled “Australian literature in the Twentieth Century” and was to be published in June. On 18 July, The Albury Banner and Wodonga Express, reports on this work, now titled Modern Australian literature, describing it as ‘an interesting “measuring up” of Australian literary work from 1900 to 1923’. Vivian Smith, editor of UQP’s Nettie Palmer anthology, which includes this work, says the piece “is significant for what it reveals of the expectations and hopes of the time”, and also that

Nettie, like Vance, was concerned for the relationship between a national literature and the national experience behind it, but both explored this relationship in a tentative and programmatic way and had no readymade formula to account for it.

Nettie has appeared here several times, and will again, but I’ll leave her here for now. (Except, I’ll share that the Goulburn Evening Penny Post (23 October 1924) reported that she gave her prize money to the “Blinded Soldiers”.)

My initial idea was to write a post about this Lothian Prize, but I’m not sure it continued. However, I’ve written posts about publishers before, and Lothian seemed perfect for another.

By all accounts, Louisa Lawson was quite a force. A poet, writer and publisher, as well as a suffragist and feminist, she was fully engaged in the country’s literary and political life, but is most remembered now for the latter, particularly her feminist causes.

By all accounts, Louisa Lawson was quite a force. A poet, writer and publisher, as well as a suffragist and feminist, she was fully engaged in the country’s literary and political life, but is most remembered now for the latter, particularly her feminist causes. Both Olga and her son Chris Masters were journralists. Chris still is. Olga commenced work as a journalist when she was only 15 years old, but through her relatively short career, she also wrote novels, short stories and drama. Her career as a published writer of fiction was very brief, with The home girls short story collection being published in 1982 and Loving daughters, her wonderful first novel, published in 1984. It is Australian literature’s loss that she died just as her fiction career was taking off.

Both Olga and her son Chris Masters were journralists. Chris still is. Olga commenced work as a journalist when she was only 15 years old, but through her relatively short career, she also wrote novels, short stories and drama. Her career as a published writer of fiction was very brief, with The home girls short story collection being published in 1982 and Loving daughters, her wonderful first novel, published in 1984. It is Australian literature’s loss that she died just as her fiction career was taking off. Multi-award-winning author Thomas (Tom) Keneally has published over 40 novels, from his 1964 debut novel, The place at Whitton, to his most recent 2020 novel, The Dickens boy. He is best known for his Booker prize-winning novel, Schindler’s ark, which was adapted to the Academy Award winning film, Schindler’s list.

Multi-award-winning author Thomas (Tom) Keneally has published over 40 novels, from his 1964 debut novel, The place at Whitton, to his most recent 2020 novel, The Dickens boy. He is best known for his Booker prize-winning novel, Schindler’s ark, which was adapted to the Academy Award winning film, Schindler’s list.