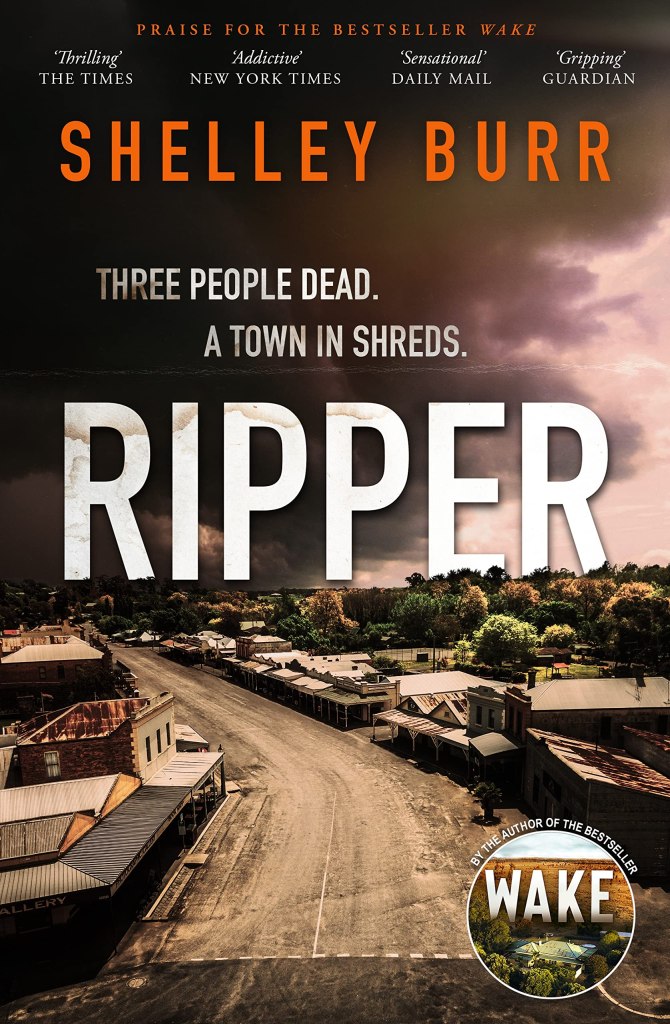

I started my recent post on Shelley Burr’s crime novel Ripper with a statement that crime novels are often written in series and that I am not a big series fan. Ripper looked at the start to be a standalone novel, but a few chapters in the protagonist from her first novel Wake appears. From then on, his voice is irregularly alternated with the novel’s main voice. But, more on that anon.

When I started reading Ripper, then, and thought it was going to be a standalone novel, I considered starting my post with singing the praises of standalones, but then, finding it wasn’t as it seemed, I shelved that issue for another day – like today. I did a little browser searching on the topic and found some useful discussions. They included ideas I’d considered, but some new ones too.

This topic is not specifically Australian, but there are many Australian crime novelists, and most of the ones I know, which is a smidgeon of what’s out there, write series. Crime is not the only genre in which series are common, of course, but it’s the one I’m using to exemplify the issue.

Here is a small selection of Australian crime, mostly authors I have reviewed or would like to read:

- Garry Disher: the Peninsular Crimes and the Hirsch novels (my review of Bitter Wash Road)

- Sulari Gentil: the Rowland Sinclair historical fiction/crime novels (the first of which I gave to my Mum for her last hospital stay)

- Chris Hammer: the Martin Scarsden, and the Ivan Lucic and Nell Buchanan novels (some of which I’ve given to Mr Gums and Daughter Gums)

- Dorothy Johnston: the Sandra Mahoney novels and the Sea-Change mysteries (my review of Through a camel’s eye)

- Dermal McTiernan: Cormac Reilly novels (my Meet the Author post)

- Angela Savage: the Jayne Keeney novels (my review of The dying beach)

- Peter Temple: the Jack Irish and the Broken Shore novels (my review of Truth)

- Emma Viskic: the Caleb Zelic novels (my review of Resurrection Bay)

I have also read some Australian stand-alone crime – Emily O’Grady’s The yellow house and Emily Maguire’s An isolated incident, being examples. These are more likely to be promoted as “literary crime” as against “genre crime”, though the distinction is loose and not necessarily helpful.

Anyhow, here are some ideas on the subject…

On series

My non-preference for series is based on a few things, the main one being that I read to hear different voices in different settings about different people, places and ideas. Series novels tend to be set in the same place and milieu, with some continuing characters. Another reason is that I like to be challenged by different approaches to story-telling a story, but series novels tend to follow a formula. It might be a good formula, the writing and characterisation might be great, but it risks becoming familiar rather than challenging or exciting.

These reasons relate in fact to what the Kill Zone named as the single biggest advantage to a series, for both writer and reader. Series, they say, provide “comfort food for the imagination”. However, they also recognise the risk that series can become formulaic.

Another issue for me is the amount of backstory that novels in series tend to include. I guess that’s for readers who start a series in the middle, but if you have read the previous novels, it can be irritating. The Kill Zone suggests that this backstory aspect is a challenge for writers too: “How much backstory does the author include in subsequent books without boring the dedicated series fan or confusing the mid-series pick-up reader?” Good question. The Career Authors site looks at it this way: “You want to make sure,” it says, “that each series title is a potential standalone, so that you can tell readers you don’t have to read my books in order!”

British crime writer Carol Wyer writes about the work involved in writing a series. She says:

You’ll need to know your characters inside out, especially those who will appear in each book, and you must continue their personal stories, weaving them in between each storyline and… you need a theme, one that permeates each book and links them all. It must be something that hooks your readers, so they will want to read the next book, maybe another overriding storyline or simply reader investment in each of your main characters.

She has “notebooks and manilla files” for every character, recording their likes and dislikes, how they pronounce things, and so on. The Career Authors site also describes in some detail what writing a series involves for an author. You can’t kill the main character off, for example!

Still, says Wyer, “the rewards are huge” because authors are usually bereft when they end a book and have to “say goodbye to the characters”. With a series they don’t have to!

On standalone

I’ve already implied why I like standalone novels. The Kill Zone, looking at it particularly from the series author’s point of view, says that “the advantage of writing a standalone … is it can bring on a breath of fresh air for you and the reader”. A standalone, that is, lets a writer explore or experiment with new approaches, techniques, subjects, and it lets the reader see new talents in a loved writer. However, the Kill Zone warns writers to not stray so far from their norm that their fans won’t recognise them.

On a Kindle discussion board, I found the warning that “standalone genre novels can be harder to sell”.

Happy mediums

Series vs Standalone looks like an either-or situation, but, is there a happy medium? Well, yes, there is. One is the approach that Shelley Burr took in Ripper. It is set in a different location, and has a different main protagonist, but the protagonist from her first novel plays a subsidiary investigating role from another location. The Kill Zone, in fact, suggests something like this when it recommends that authors could “touch on something” in their new book that had “appeared in a previous series”.

The other idea, one that has a foot firmly planted in both camps is the “trilogy”. While she didn’t frame it in terms of this debate, Dervla McTiernan, in the meet-the-author event I attended, said about writing her Cormac Reilly trilogy, that she didn’t want to write a long procedural series, because they tend to be episodic without overall narrative arcs. She wanted to challenge her character Cormac; she wanted him to have a narrative arc which would see him changed by the end. That said, she did admit that Cormac might re-appear some time in the future!

Some sources

I found a few discussions on the internet that made some good points regarding the series vs stand-alone debate. The main ones were the Kill Zone blog (a joint blog), Carol Wyer, and Career Authors.

I’d love to hear your thoughts, whether you are author or reader. Do you prefer one or the other, or don’t you care? Over to you …