Last week’s post focused on attitudes to writing about the war during the interwar period, particularly in relation to the realism of books like Erich Maria Remarque’s All quiet on the western front. This post continues the discussion, but will share some specific war writing from the article that inspired this series.

But first, a reminder of the main concern expressed about the war novels coming out in the late 1920s to early 1930s. L.S. Avery, former Secretary of State for the Dominions, explains it in his statement that the

fashion of “stench warfare” writing would pass, and the war would take its place as the marvellous effort and an amazing romance in which no part was more amazing that that played by the Australians.

He was proposing the toast of “The Commonwealth of Australia” at a dinner at the Royal Society of St. George, London, in May 1930. I can’t resist digressing to a description of the dinner, which:

was reminiscent of old times. The roast beef of Old England was borne around the room, preceded by the crimson cross of St George, and heralded by the roll of drums and the playing of fifes. Only Empire food, including Australian apples, was served.

No wonder they looked to war being presented as a “marvellous effort” and “an amazing romance”, eh?

Recommended war writing

Now to Non-com’s article on the “AIF in Literature” in Perth’s The Western Mail (30 April 1936).

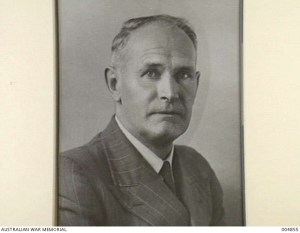

Who is this Non-com, I wondered? Some googling took me to the State Library of Western Australia photographic database where I discovered that he was Cyril Longmore (1897-1964), of The Western Mail, which, the photo notes said, preferred to use pseudonyms. Of course, I wanted to find out a bit about Cyril Longmore. More googling found the portrait I’ve used here on the Australian War Memorial (AWM) photographic database. Its notes said he’d been “appointed Military Commentator of the Department of Information” in 1941. At this point, I returned to Trove and found an article in Launceston’s Examiner (21 January 1941) about this appointment. He was to replace one Major Jackson who was returning to military service. The Examiner says that Longmore was recommended by C. E. W. Bean (the respected war historian), and that he had served in “the last war with the 44th Battalion and attained the rank of captain”. Post-war, it says, he “has been actively connected with Australian journalism and has written extensively on military subjects, of which he is a close student”.

So, not only did I find out who Non-com was, but I also ascertained his credentials for writing the article he did. (Oh, and the AWM also told me that he was The Western Mail‘s editor!)

His article is based on a talk he did for an “Australian Authors” session on the “National station” (by which I presume he means the ABC). Despite his credentials, he commenced by saying that

I speak on the A.I.F. in literature with diffidence, being no authority on the subject, although I have read most of the Australian war books, and my work has led me to make some study of them during the last few years. In this talk I am not touching Dr. Bean’s great historical work on the A.I.F., nor am I mentioning several Australian war novels. I have taken those books produced during the last five years which purport to be the experiences of those who wrote them—men (and a woman) who served in Australian units.

In other words, his focus is not novels but memoirs and the like, but I think they are relevant to our discussion. I’m glad he includes women (albeit “a woman”, parenthetically!) It’s now 1936, but he too references All quiet on the western front, negatively, saying it “seemed to stimulate the imaginations of authors all over the world, for each seemed to try to outwrite the others in his trail of ghastliness”.

Anyhow, here’s his list, in his order:

- Red dust (1931), by JL Gray, writing as Donald Black: Subtitled “A classic account of Australian Light Horsemen in Palestine during the First World War”, this was apparently written during the war as a diary, and, says Longmore, “is a remarkable description and analysis of the life and deeds of the Australian trooper”.

- The desert column (1932), by Ion L. Idriess: Also a story in diary form of the Lighthorsemen, but at Gallipoli, Sinai and Palestine. Longmore says that “some of his pen-pictures are epics of war realism”. (As realistic as Remarque’s, I wonder?)

- Hell’s bells and mademoiselles (1932), by Joe Maxwell, VC, who served with the 18th Battalion. Longmore says it is “an enjoyable volume, but there is some fiction woven into its truth, especially about the mademoiselles. The best feature in it is its faithful reproduction of types” that diggers would recognise.

- Jacka’s mob (1933), by E. J. Rule: Longmore describes it as “a true and vivid picture of experiences with the 14th Battalion, A.I.F., by a man who was intimately associated with everyone and everything of which he wrote. It is no glowing picture of faultless knighthood.” He continues that “Knighthood and chivalry were in every unit in the A.I.F., in all the fighting armies, but even knighthood experienced the chill pangs of “wind-up” at times, and it is in the correct proportions in which the author has presented these and many other of the minor personal details that somehow escape the novelist [my emph!] that makes Jacka’s mob so valuable.”

- The gallant company (1933), by H.R. Williams: Subtitled “An Australian soldier’s story of 1915-18”, it is praised by Longmore as the “best of all the Australian war books … It is not highbrow literature and there is no forced striving for effect. But it is a faithful, vivid narrative of an Australian unit and of its individuals, with just sufficient historical background to give them their proper atmosphere. A readable book that does justice to the great achievements of the digger and puts “war, wine and women” in proper perspective”.

- Iron in the fire (1934), by Edgar Morrow: About the author’s experience of the 28th Battalion, Longmore praises it for being “the truest and most comprehensive war book of the lot” in terms of capturing the “inner feelings — sinking in the pit of the stomach before zero; sorrow at the death of a comrade; joy on receipt of a letter, or a parcel, or leave, which we all tried to hide under a mask of unconcern.” It’s “critical”, he says, and “all may not agree with the criticisms of authority, but it is a fine book”.

- The grey battalion (1933), by Sister May Tilton: The one book by a woman, “the only one of its kind”, this “gives its readers an idea of the great courage and endurance that were needed by these women in their unenviable task of nursing the sick and maimed victims of war back to health and strength”. Interestingly, he notes that “what they suffered themselves no one will ever know”!

- The fighting cameliers (1934), by Frank Reid. By a member of the A.I.F’s Camel Corps, but Longmore sees it as “the one disappointing Australian war book” because “colour and realism are lacking”.

- Crosses of sacrifice (1932), by J. C. Waters. Differs from the others because the author is a journalist who was too young to go to war but had “toured the battlefields and war cemeteries of the world”. Longmore says he “brings a reverent and understanding mind to … his subject”. He writes more on this book than on any of the others!

Do you read war histories, diaries or memoirs?