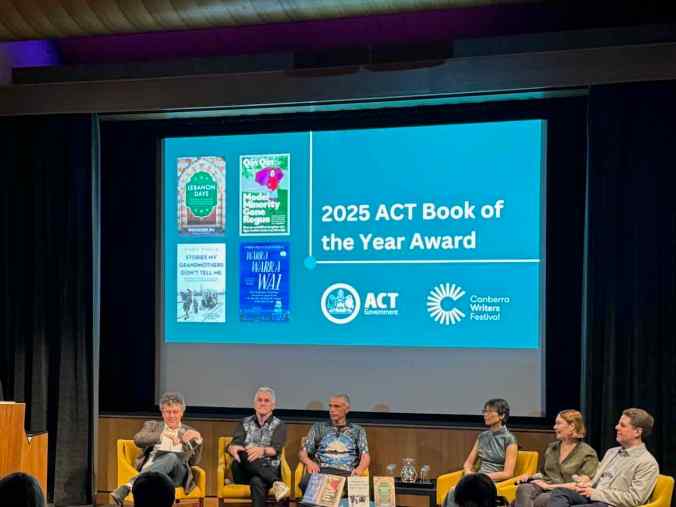

Kate Grenville and Paul Daley with Craig Cormick

The program described the session as follows:

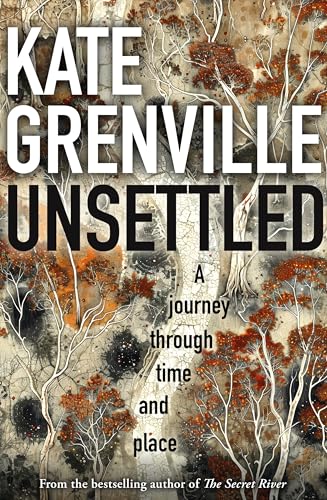

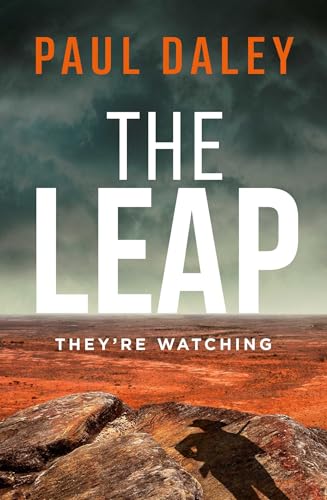

Kate Grenville’s ancestors were ‘the sharp edge of the moving blade’ of colonisation through the Hawkesbury region – the subject of her bestseller The Secret River. Now in Unsettled: A Journey Through Time and Place, she reflects on the reckoning that comes with truly confronting the past and her family story. She’s joined by Paul Daley, whose novel The Leap examines fear and violence in a frontier town. Two years after the Voice referendum, this timely conversation is about non-Indigenous Australians doing the work and personally reckoning with the past. This conversation, moderated by author Craig Cormick (Warra Warra Wai) will reflect on the role of non-Indigenous authors in contemporary writing exploring Indigenous issues.

You know you are not with the zeigeist when the session you choose is not in the big venue. This was the case for me with my last two sessions of the day, and to be honest, I was unsure about whether I wanted to attend this session. Did I want to hear more of us white peole talking about our guilt. It’s not about us. And yet I’m a white person so I decided there might be something new for me to think about, or another way of thinking about the issue. As it turns out, there was … read on …

Craig Cormick started the usual way – by acknowledging the traditional owners but also asking us to say hello – Yuma – in the local language. He then introduced the writers, noting in particular that Kate Grenville’s The secret river was ranked 20 in the ABC’s Top 100 books of the 21st Century. He then explained that we would be talking about white fellas writing black stories, black history.

On how a white writer writes respectfully about black issues (to Kate)

There is no simple answer, but it involves a big cloud of context requiring awareness – of truthful knowledge of a dark history, of what might be the effect of what you write on First Nations people (which can include grief, insult, rage), and of how non-Indigenous readers will read what you write. The respectful way might be not going there, or engaging in consultation, or …

Do we need more than good intentions (to Paul)

Paul thinks of the journalists and anthropologists who wanted to save, hoard stories and culture – the equivalent of what literary writers want to do – so he asks himself the question “why am I going there?” He turned to fiction after years of journalism, as medium to tell about an Australia that is not seen enough. He said that both fiction and nonfiction requires respect, but fiction can be more “arbitrary”. Who do you consult when you are writing a character. It can be laborious. You need to forget deadlines.

On writing from an Aboriginal perspective (to Kate)

She never has – except very briefly in her novel Joan makes history. She wouldn’t do that now. She wrote 25 drafts of The secret river. The consciousness of the book was based on her white ancestor, but is about his relationship with local indigenous people. She started by giving them some dialogue, but felt she was othering or diminishing them, so she tried to individuate them without stepping into their world. Her latest book is nonfiction involving a road trip, which sort of mirrors Craig’s (in Warra warra wai). It was about private soul-searching, which she feels must be done before we talk to First Nations people.

On writers not including First Nations people in rural noir (to Paul)

The three main reasons writers give are: they don’t want to locate their book, or, they don’t want to upset their conservative readers, or, it’s just too hard! But, said Paul, many books are about white people’s crimes against white people on lands owned by others who are never mentioned. The leap is like an update of Wake in fright, which was reflective of the white male Australia of the time.

Is it too hard to go there (to include First Nations people) (to Kate)

She looked at Eleanor Dark’s 1941 The timeless land, in which Dark entered the consciousness of an Aboriginal character. It would be wrong now, but at the time Dark was “writing into a profound silence”. She was, in fact, revolutionary.

But, as long as white writers are aware of boundaries, they can “go there”.

Are there boundaries writers shouldn’t cross (to Paul)

Yes, he wouldn’t write in a First Nations first person voice, would not get into secret sacred areas/places/topics, and would not embed a story in a First Nations community.

The conversation then further explored this idea of boundaries, and issues like consultation.

Craig shared a comment made by Harold Ludwick (with whom he collaborated on the novel On a barbarous coast, my review) that “we earnt your way of thinking more than you learnt ours”.

Kate said that with her road trip, she did not speak to First Nations people. She believes that we want to jump too quickly to reconciliation, to forgiveness, but she believes we need to do soul-searching (a bit like you do in “time-out”) about what it means to be a non-indigenous person in Australia. She didn’t want to ask for things from First Nations people, like asking them to explain their feelings to us or to forgive us. She talked about the first time she asked Melissa Lucashenko to read a book (as a sensitivity reader I presume). Lucashenko said, “Sure, but pay me”. Another time, she said, “Yes, but first read White privilege“. In other words, she asked for something in return.

Paul picked up this idea of “wanting” things from First Nations people. He said he will ask friends to read his manuscript. He realises it is burden, and he explains that the end product is his, not their responsibility. If, after consultation, they say they don’t want him to do it, he wouldn’t.

Paul drew an analogy between Australian writers’ current concern about AI ripping off their work, and how First Nations’ people’s stories have been ripped off for so long.

The discussion turned to some examples of “ripping” off, such as last year’s controversy over Jamie Oliver’s children’s book, and its egregious depictions of First Nations people and their practices.

Overall, consultation is a difficult thing. Who you consult, can be a fraught issue. It is often, for example, not the Land Council. They do not necessarily represent the elders. Consultation can exacerbate divisions. (Some of this issue about who speaks for whom was covered in Wayne Bergman and Madelaine Dickie’s Some people want to shoot me, my review.)

There was a Q&A, but most of it revisited ground already covered. For example, one audience member spoke of writing a story inspired by a First Nations person. He had consulted the relevant elders and descendants, and they were comfortable. He had checked his motivation. But AIATSIS had said it wasn’t his story to write. The panel agreed this was difficult. There are no answers. Sometimes, said Kate, you just have to take a risk. Paul agreed, but gave the example of Jesus Town. He had a misgiving on the eve of publication, so pulled back, reworked and published later.

There was agreement that it was great to see First Nations people now telling their own stories, and about experienced writers doing all they can to help them.

The discussion ended on two points that encapsulated the discussion perfectly and validated my decision to choose this session:

- that writing in the voice of a person in which you don’t have lived experience [however you define that] would not be adding to the sum of human knowledge

- that in relation to our history, there is no atonement. We have to live with that.

Canberra Writers Festival, 2025

Reckoning

Saturday 25 October 2025, 12-1pm