During 2022 and 2023, I wrote a series of posts on Australian literature as it was read, and thought about, a century earlier, in 1922 and 1923. Last year, I researched 1924, with a view to doing the same, and in fact heralded the upcoming 1924 series, but didn’t end up writing any posts. This was partly because many of the concerns were the similar to those of 1923, and partly because other ideas overtook me. But there were some interesting things said, so, nearly a quarter of the way through 2025, I’ve decided to write at least a couple of posts relating to 2024, starting with the Bookstall Company’s Bookstall series of Australian fiction.

This series of cheap paperbacks of Australian novels, as I have posted before, were introduced to the Australian market in 1904. I featured them in posts on 1922 and 1923, and am here updating us with 1924’s output. The series continued to serve its purpose, it seems, of supporting Australian writers as well as of providing reading matter at an affordable price. The Queenslander, introducing two new books in the series, started its brief article on June 7 with:

Australian novelists owe a great deal to the New South Wales Bookstall Company, which, during the last few years, has published more than 200 novels by Australian writers.

Sydney’s The Labor Daily made a similar comment on December 16.

As far as I can tell from the research I did, publication did slow down with significantly fewer books published in 1924 than in 1923. Here is what I found.

- Roy Bridges, By mountain tracks

- Ernest Osborne, The copra trader

- S.W. Powell, The trader of Kameko: South Seas

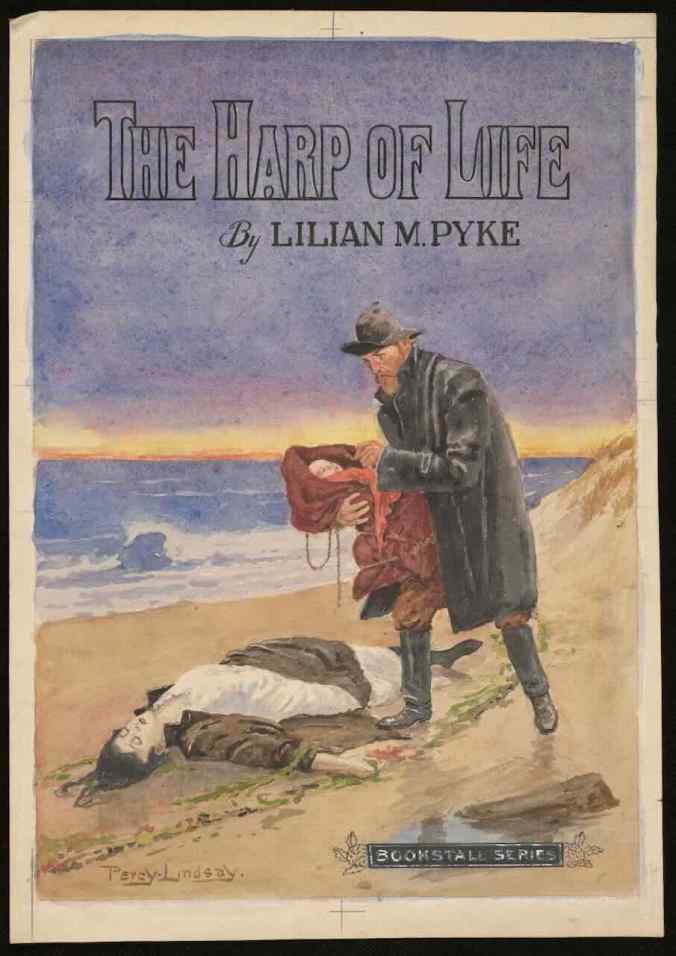

- Lilian M. Pyke, The harp of life

- W. Sabelberg, The key of mystery

- H.E. Wickham, The great western road

So, just 6 books, compared with 20 in 1923, and only one by a woman. (There may have been a few more, but it’s these six that kept popping up in my searches.) Most are adventures of some sort and most feature a “love interest”.

Bushranger stories were still popular at this time, even though the worst of the bushranger era had ended by the 1880s. Both Roy Bridges’ By mountain tracks and Wickham’s The great western road belong to this genre. That said, Bridges’ book is described in The Queenslander (7 June) as “a story associated with the Kelly gang, but the theme generally is that of a romantic love episode”.

Two of the books, those by Pyke and Sabelberg, seem to be contemporary stories, Pyke’s being a tangled story about a waif rescued from the arms of its dead mother on a Queensland beach, and Sabelberg’s a mystery/thriller.

Adventures in the South Seas were apparently making a come-back around this time, with Jack McLaren (who appeared in my 1923 post), Ernest Osborne and S.W. Powell all setting books there. Hobart’s World (12 February) wrote of Powell’s novel as being “full of incident and adventure, and aglow with the rich color of the South Seas. A good shilling’s worth.” This latter point was frequently mentioned in reviews of Bookstall books. Indeed the World, in the same article, said of Wickham’s novel that

“Most of the characters in the book are well-drawn, and convincing, and there are humorous episodes to relieve the tragedies, and compensate for the author’s rather marked tendency to waste words in trite moralisings, and in a too-conscious elaboration of dialogue. Just the same, it is a marvellous shilling’s worth.”

Most reviewers of these books understood their intention as escapist reads or, what we would call today, commercial fiction, and wrote about them within that context. They either praised the works – with one, in fact, describing Osborne’s novel as “brilliantly written” – or, where they were critical, they tempered it with this understanding, as in the Powell example above. However, a report in the Murray Pioneer and Australian River Record (5 December) was not so generous. Sabelberg’s The key of mystery, it said, “is a crude murder story, crudely written”; Powell’s The trader of Kameko, “is a story, with no literary merit, of a white man, two brown girls and a hurricane”; and Wickham’s The great western road “is a story of the early gold rushes in N.S.W. of the same crude character as the other two”. Of course, reviewers do pitch their writing to their audience. Perhaps readers of the Murray Pioneer and Australian River Record had more refined tastes, and more money to spend, and our writer recognised that?

Some newspaper articles noted that some of these writers had already developed their writing skills in other forms. Sabelberg and Wickham, for example, are described as established, successful short story writers, and Lilian Pyke as a writer of “capital” stories for boys and girls – all of which proves, I guess, the point about Bookstall’s role in supporting Australian writers. How better to cut your teeth as a novelist than with a company like this?

And I will leave 1924 on this point. Life has been very busy this last week … so I have not been able to pay as much attention to reading and my blog as I’d like, but I do hope to post a review this week.