In the first decades of the 20th century, a family of sisters made some splash on Australia’s literary scene. I have already written about the eldest of them – Louise Mack – but there were also Amy (this post’s subject) and Gertrude, all of whom appeared in newspapers of the time as writers of interest. They were three of the thirteen children of their Irish-born parents, Rev. Hans Hamilton and his wife Jemima Mack. As with many of my Forgotten Writers articles, I researched Amy Mack for the Australian Women Writers’ blog, where we have several posts devoted to her.

Amy Mack

Amy Eleanor Mack (1876-1939) was a writer, journalist, and editor. She was six years younger than the more famous Louise, and, says Phelan in the Australian dictionary of biography, was “less temperamental … and lived more sedately”, which is not to say she lived a boring life.

Mack began work as a journalist soon after leaving school, and from 1907 to 1914 was editor of the ‘Women’s Page’ of the Sydney Morning Herald. She married zoologist Launcelot Harrison, in 1908, and in 1914, they went to England where he did postgraduate work at Cambridge, before serving in Mesopotamia as advisory entomologist to the British Expeditionary Force. While he was away, Mack worked in London as publicity officer for the ministries of munitions and food.

The couple returned to Sydney after the war, with Launce becoming professor of zoology at the University of Sydney, and Amy continuing her literary career among other roles and activities. They did not have children. According to Phelan, after her husband died she continued to publish occasional articles, but her impulse to write faded as her health declined. She died of arteriosclerosis in 1939.

Works

Amy Eleanor Mack’s subject was nature, and she wrote about it in newspapers and books, for adults and children. Australian ecologist, Manu Saunders, writes on her blog that:

Australia has a wonderful heritage of nature writers, many working before nature writing was ‘a thing’. The national collection of Australian children’s books about native wildlife is inspiring. Even more inspiring, many of Australia’s best nature stories were written in the early-mid 19th century, and mostly by women.

And one of those women, she continues, was Amy Eleanor Mack. (I have written before on one of our early colonial nature writers, the pioneering Louisa Atkinson.)

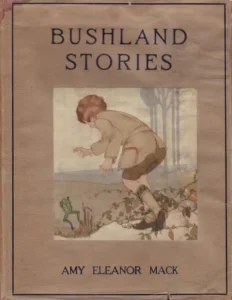

Mack’s first publications were two collections of essays, A bush calendar (1909) and Bush days (1911), which were compiled from articles she’d written for the Sydney Morning Herald. She also wrote two popular children’s books, Bushland stories (1910) and Scribbling Sue, and other stories (1915). Wikipedia lists 14 books, many of which were first published in newspapers, but all of which have nature-related titles, like The Fantail’s house (1928) and The gum leaf that flew: And other stories of the Australian bushland (1928).

Her books were well-reviewed in the newspapers of the time. Her first, A bush calendar, was described by Sydney’s The Farmer and Settler (26 November 1909), as charming, “a sympathetic review of bird life and plant life in the Australian bush during the four seasons of the year”. But what is interesting is what they say next:

It is the kind of book that ought to be on every girl’s bookshelf, and every thoughtful and intelligent boy’s also, being not only an exceedingly pleasant thing to look at and to read, but one calculated to induce in many a desire to get to know more of nature in some of her sweetest phases.

I’m intrigued by the gender differentiation – “every” girl, but only “every thoughtful and intelligent boy”. These sorts of insights into other times make researching Trove such a joy. Anyhow, the review also suggests that it would be “a delightful remembrancer for Australians abroad”. A year later, on 26 November 1910, Sydney’s The World’s News, reviewed Mack’s children’s book, Bushland stories, calling it an improvement on A bush calendar. It comprises a “collection of fables, allegories, fairy tales, or whatever one chooses to call them” which, the News says, has “created a folklore for young Australians”. In it, Mack personifies nature, with birds, beasts and fish all acting and speaking “like rational beings”. Each story has a moral but there is none of the “preachiness, which many youthful readers shy at”.

Reviews of later books continue in a smilier vein. In 1922, on 6 December, Lismore’s Northern Star writes about Wilderness, which, it says,”tells in a most interesting way of the fascinations of a piece of land which once had been a garden, planted with fruit trees and roses, but which has been neglected until the bush reclaimed it for its own”. This is the book that Saunders writes about in her blog in 2017. The book had been originally published in three parts in the Sydney Morning Herald. Saunders explains that it

tells the story of an unnamed patch of wild vegetation in Sydney (Mack never names the city, but given the original publisher and the wildlife she describes, it seems pretty obvious). Mack describes the plot so vividly and intimately that you imagine yourself there. You can visualise Nature reclaiming this plot of land, left untended after the keen gardener who owned it passed away.

Saunders then describes its content, including examples of the nature Mack describes, as well as her attitude to it and her observations. Saunders was surprised but “weirdly” comforted to find conservation messages that are still relevant today embedded within the book.

Legacy

Australian feminist Dale Spender, in her book Writing a new world, says a little about Amy Mack, though she spends more time on Louise. However, she makes a point about the Mack sisters and their peers, Lilian and Ethel Turner:

Lilian and Ethel Turner, Louise and Amy Mack were part of a small group of spirited literary pioneers who at very early ages adopted public profiles in relation to their work. When they moved into the rough and tumble world of journalism – when they entered competitions, won prizes, and published best-selling novels before they were barely out of their teens – they broke with some of the long-established literary conventions of female modesty and anonymity. They sought reputations and in doing so they show how far women had become full members of the literary profession: they also helped to pave the way for the equally youthful and exuberant Miles Franklin whose highly acclaimed novel, My Brilliant Career (1901), was published when the author was only twenty-one.

Ever political, Spender argues that had it “been brothers (and ‘mates’)” who created the sort “colourful and creative community” these sisters did, and achieved their level of literary success, we would have heard of them. Books would have been written about ‘their “literary mateship” and they would have been awarded a place in the readily accessible literary archives’. But,

because these writers were women, and because they have been consigned to the less prestigious categories of journalism and children’s fiction (both a classification and a status with which I do not agree) they, and their efforts, and their relationships – to rephrase Ethel Turner – go unsung.

Amy Mack is less well-known now than her sister Louise, and certainly less well-known than Ethel Turner, but in her time she was much loved. However, even then, she didn’t always get her due, as a reader wrote to The Sydney Morning Herald on 16 April 1935:

With reference to the articles on Australian women writers in the Supplement, one is surprised at the omission of Amy Eleanor Mack, who surely wrote two of the finest books for children ever published in Australia. In “Bushland Stories” and “Scribbling Sue” the true spirit of our bushland has been preserved with a charm and sincerity all its own, and I think I am right in stating that, with the exception of Miss Ethel Turner’s “Seven Little Australians,” no books published in Australia for children had greater sales.

Four years later, announcing her death on 7 November 1939, The Sydney Morning Herald said that her work “had a mark of reality about them that found for her an increasing circle of readers”, but it was “A.T.” of North Sydney, who wrote to this same paper on 8 November, who captured her essence:

Her culture, wit, and broadmindedness, and her marvellous sense of humour made her a figure in the northern suburb in which she resided.

Sources

Nancy Phelan, ‘Mack, Amy Eleanor (1876–1939)‘, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 1986.

Manu Saunders, “The wilderness: Amy Eleanor Mack“, ecologyisnotadirtyword.com, 4 March 1917

Dale Spender, Writing a new world: Two centuries of Australian women writers, originally published by Pandora Press, 1988 (sourced in Kindle ed.)