Back in 2023, I briefly mentioned the Australasian Book Society (ABS) in my Monday Musings post for the 1962 Year Club, adding that the society deserved its own post. Finally, here it is, albeit still introductory. There is a lot to research and tease out about this initiative, and I am not planning to write a thesis.

The ABS has a very brief page in Wikipedia, which tells us that it was a cooperative publishing society that ran in Australia between 1952 and 1981. It was co-founded in Melbourne by trade union leader and community activist George Seelaf, at the suggestion of novelist Frank Hardy.

In 2021, the ANU offered a Zoom seminar, titled “The Australasian Book Society: Making a Literary Working Class During the Cultural Cold War”, with Professor Nicole Moore, UNSW Canberra, as speaker. The promotion explained that one of the Society’s “masthead aims”, was

“To encourage mass participation in and responsibility for the publication of progressive Australian literature”.

According to the Zoom promo, it was “a mid-twentieth-century, book-club style, cooperative publisher with a subscription model that promised four books a year to members and distribution through unions, industry associations, education organisations and the communities of the organised left in Australia, including the communist party”. Wikipedia suggests that it was “perhaps a unique venture in Australian publishing history”. The Zoom promo explains that it produced “a long list of notable books by Australian, New Zealand and other regional authors through the polarised years of the cultural Cold War”, and was also a “conduit for Eastern Bloc publishers”.

However, there is apparently still much research to be done into “its model of production and the readership it mobilised”, into how successful it was in “creating a literary working-class readership”, and more. Hopefully someone is out there working on this.

In the meantime, I’ll share some things I found through Trove. Tribune announced the establishment of the society with much enthusiasm. On 28 May 1952 it said that

THE formation in Melbourne the Australasian Book Society is being widely hailed as an event of outstanding importance to every Australian reader and to all our serious writers.

Six years later, on 4 June 1958, it carried an article by the writer and Communist, Judah Waten, who was the Society’s chairman. He believed strongly in the society and its value to Australian culture. He wrote:

FROM its inception the Australasian Book Society has taken an active part in the great contemporary battle of books and ideas between the forces of reaction and the forces of progress.

On the side of advancement, the ABS, as a co-operative organisation of writers and readers, has published books by writers who have endeavored to describe life truthfully and thus deepen our understanding of human relations and problems.

Unlike today’s fashionable writers who preach pessimism and man’s helplessness, the writers whose books have been published by the ABS look to the future as well as the past, arousing in their readers a determination to end the evil conditions which give rise to unhappiness.

These writers, perhaps more than any other group of writers in the country, have continued the democratic traditions in our literature and are outstanding exponents of Australian realism.

Back in 1953, however, Melbourne’s more conservative Weekly Times (6 May) noted that not all readers who subscribed to the Society knew who was behind it:

Many people throughout Australia and New Zealand have joined the society unaware of its association with Communists.

The society’s printed publicity said they would get “worthwhile books at the lowest possible prices.” Instead, they have got books by well-known Communist authors such as Frank Hardy.

It doesn’t seem like the ABS hid its origins, but it probably didn’t shout it out either.

Anyhow, ten years after its inception, in 1962, the ABS was still going, and newspapers carried little tidbits of news about its achievements, such as:

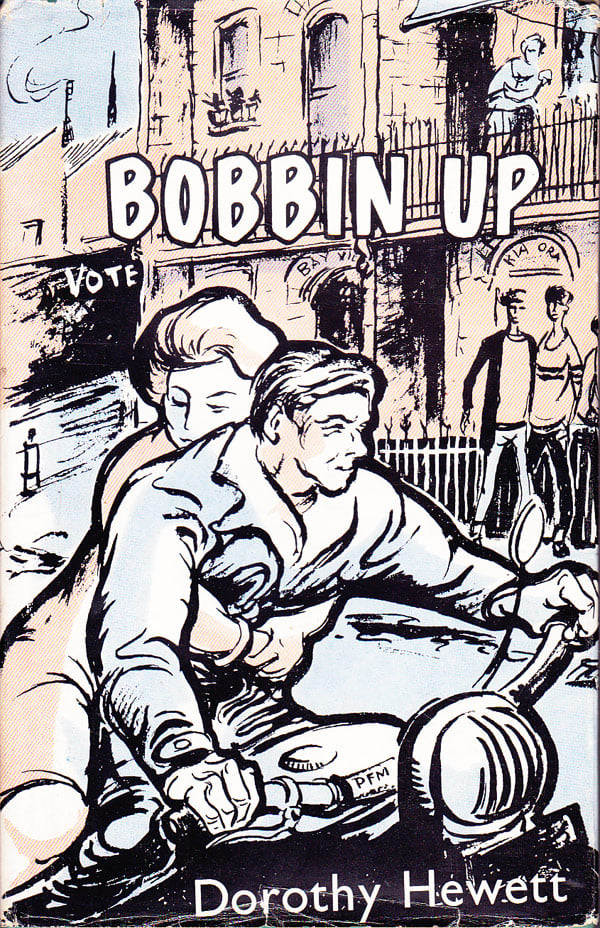

- Many Australian books published by ABS were finding their way into foreign translated editions: Dorothy Hewitt’s Bobbin up (see kimbofo’s review), about women factory workers, had already been published in the German Democratic Republic, was soon to appear in a Rumanian edition, and Hungarian and Dutch editions were looking likely (Tribune 17 January 1962); Judah Waten’s Shares in murder, was being serialised in the New Berlin Illustrated magazine, with book editions being published in both Germany and Czechoslovakia, and a Soviet edition expected “at any time” (Tribune 7 February 1962).

- Gavin Casey’s Amid the plenty, was, according to R.T. (Canberra Times 24 March), a truly Australian novel that bucked the modern anti-colloquial world-aware trend. “Most of the self-elected realists in Australian writing spend too much of their time explaining their characters”, says R.T., but “Casey lets them explain themselves in rip-roaring, hell-for-Ieather, damn ’em all slang”.

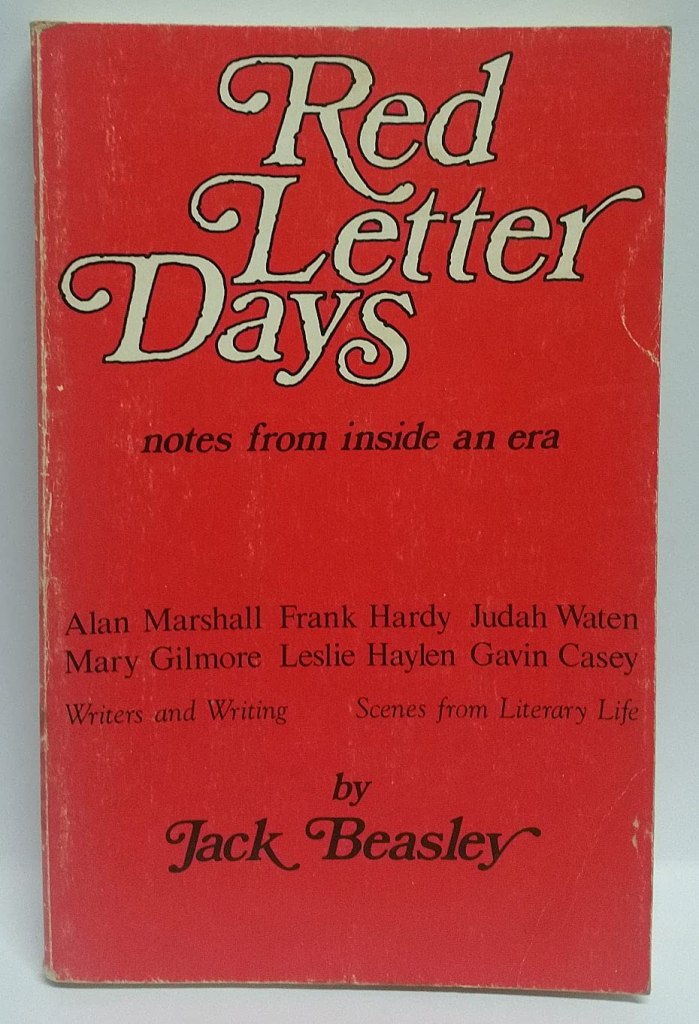

- Ron Tullipan toured northern New South Wales and southern Queensland with the secretary of the Australasian Book Society Jack Beasley to promote his book March into morning, which won the 1961 Mary Gilmore Award (Tribune 10 October 1962). Tullipan is recorded as saying that “Australian people are very interested in Australian literature — if it is sincere.”

As we move into the 1970s in Trove, there are still articles about books being published by the ABS, but I could find nothing in the 1980s about its demise. This could be because, for copyright reasons, fewer newspapers from more recent decades have been digitised.

I will close with a review from the Tribune (18 July 1979) of another book published by ABS, the memoir, Red letter days: Notes from inside an era, by the above-mentioned Jack Beasley. Beasley covers the writers he knew – including Judah Waten – but also the Society as a whole. Reviewer Bob Makinson discusses the pros and cons of an insider’s view, but suggests that “those who seek to examine Australia’s cultural-political history must be prepared to accept the value of studies like this”.

Makinson concludes:

The ABS has had more than its share of problems since its official formation if 1952. The founding members had different ideas about its aims: should it publish books with “progressive social content” oriented to a trade union readership, or promote Australian literature at a time when it was stifled by establishment publishers?

He goes on to say that “The ABS was forced to answer these questions during a period of extreme red baiting and sometimes heavy handed interference from the left” and then, concludes – he’s writing in the Tribune after all, that “it came through and still provides many Australian writers with their first publishing break. Tribune readers who wish to join ABS or find out more about it should write to …. In a period of cultural confusion and struggle ABS is worth supporting.”

A fascinating part of Australian literary culture, and one that’s ripe for study.