This should be my last post on Mr Haskell’s survey of the arts in Australia, and it focuses on Radio and the Movies. First though, in his section on literature, he talked about Australian readers and bookselling. He wrote that the average Australian “is a great reader; more books are bought per head of population in Australia and New Zealand than anywhere else in the English-speaking world”. He admires Australian booksellers who can’t quickly acquire the latest success. So, “they buy with courage and are true bookmen in a sense that is becoming rare in this [i.e. England] country.”

I believe Australians are still among the top book-buying nations, per capita, but I couldn’t find any supporting stats, so I may be making this up! However, I did love his commendation of the booksellers of the time, and his sense of their being “true bookmen” (as against their peers in England). He certainly wasn’t one to look down on the colonials!

“an admirable institution”

He writes about the “admirable” ABC (Australian Broadcasting Commission). He recognises that wireless has become a necessity “in a country of wide open space” because it is, for many, “the only form of contact with the world”. He says the ABC “supplies much excellent music, and at the same time appeals to the man-in-the-street through its inspired cricket and racing reports”. You all know how much I like the ABC.

BUT radio is a vice too, he says, when it is left on all day “in every small hotel, seldom properly tuned and dripping forth music like a leaky tap”. He is mainly referring here to commercial broadcasting which he describes as “assaulting popular taste by their dreary programmes of gramophone records and blood-and-thunder serials … Unlike America, they cannot afford to sponsor worthwhile programmes”. Hmm, my old friends at National Film and Sound Archive might disagree given Australia’s large and by all accounts successful radio serial industry, though perhaps much of this occurred from the mid 1940s on – i.e. after Haskell did his research.

“isn’t Ned Kelly worth Jesse James?”

Haskell has a bit to say about Australians’ love of cinema, with “the consumption per head being greater than anywhere else”. Film theatres are “the largest and most luxurious buildings” in Australian cities, but

the films shown are the usual Hollywood productions. There is as yet no public for French or unusual films.

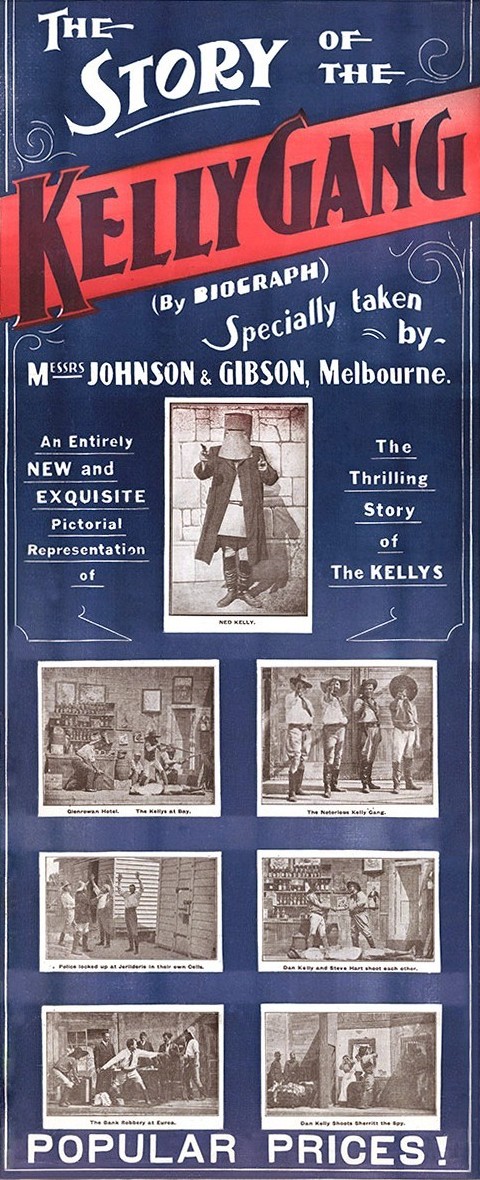

Poster for 1906 movie (Presumed Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

Australian films are being made, he said, “in small quantities” but are “not yet good enough to compete in the open market.” He is surprised that given Australia’s “natural advantages”, it had “produced so little in a medium that would encourage both trade and travel”. He goes on to describe how much people knew about America through its films -“we have seen cowboys, Indians, army, navy, civil war and Abraham Lincoln”. He suggests that Australia had just as interesting stories to tell and places to explore:

What of the Melbourne Cup, life on the stations, the kangaroos, the koala bear, the aboriginal, the romance of the Barrier Reef and the tropical splendour of the interior, the giant crocodiles of Queensland? What f the early history, as colourful as anything in America? isn’t Ned Kelly worth Jesse James?”

He suggests that films could do more for Australia in a year than his book, and yet, he says it seems “easier and safer to import entertainment by the mile in tin cans and to export nothing”!

He makes some valid points but he doesn’t recognise that Australia produced, arguably, the world’s first feature film, back in 1906, The story of the Kelly Gang – yes, about Ned Kelly. It was successful in Britain, and pioneered a whole genre of bushranging films that were successful in Australian through the silent era. Three more Kelly films were made before Haskell visited Australia – but films were pretty ephemeral, and he clearly didn’t know of them.

At the time he researched and wrote this book, 1938 to 1940, there was still an active film industry. Cinesound Productions produced many films under Ken G Hall from 1931 to 1940, and Charles Chauvel made several films from the 1930s to 1950s, but the war years were lean times, and it was in those early years that Haskell did his research. It’s probably also true that then, as unfortunately still now, Australians were more likely to flock to overseas (that is, American, primarily) productions than their own.

Anyhow, I hope you’ve enjoyed this little historical survey of an outsider’s view of Australia as much as I have – though I guess it’s all rather irrelevant, and even self-indulgent, if you’re not Australian! Apologies for that!