Serendipity is a lovely word, and is even lovelier when it touches my reading. Such was the case with my last two books, Olga Tokarczuk’s House of day, house of night (my review) and Brian Castro’s Chinese postman. The connections between them are simple and complex. Both focus more on ideas than narrative, are disjointed in structure (or, at least, in reading experience), and draw consciously on their author’s lives. They also seem to be questioning the nature of fiction itself, a question that is true of two other books I’ve read in recent times – Michelle de Kretser’s Theory & practice (my review) and Sigrid Nunez’s The vulnerables (my review). None of these books are fast reads, but they are rewarding ones.

The other thing that connects these books is that, because narrative provides more of a loose structure than a driving force and because they blend that narrative with ruminations, memoir, essay, vignettes, anecdotes, recipes even, they exemplify the idea that every reader reads a different book. This is not only – or even primarily – because we are not all men in our mid-70s with mixed ethnicity, to take Castro (and his protagonist) as an example. Rather, it is because we all think about and weigh differently the issues and ideas these authors focus on.

In The vulnerables Nunez refers to Virginia Woolf (as does de Kretser) and her “aspiration to create a new form. The essay-novel”. She also refers to Annie Ernaux’s nonfiction book The years, describing it as “a kind of collective autobiography of her generation”. I’ve digressed a bit here, but my point is that these writers have things to say about their time, their generation, the state of the world – and they are looking for better ways to say it. They are suspicious of pure narrative, and yet I think they also recognise, to some degree at least, that “story” is a way to reach people. Therein lies the tension that each tries to deal with.

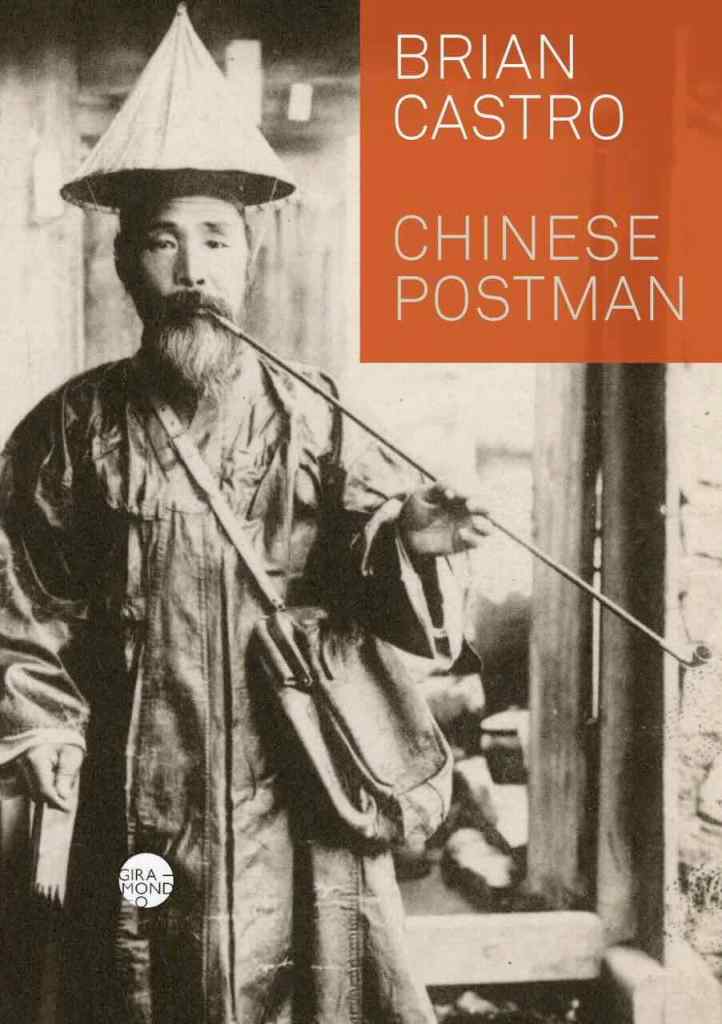

So now, Castro! There is a story, a sort of narrative, running through Chinese postman, and I’ll let publisher Giramondo explain it:

Abraham Quin is in his mid-seventies, a migrant, thrice-divorced, a one-time postman and professor, a writer now living alone in the Adelaide Hills. In Chinese Postman he reflects on his life with what he calls ‘the mannered and meditative inaction of age’, offering up memories and anxieties, obsessions and opinions, his thoughts on solitude, writing, friendship and time. He ranges widely, with curiosity and feeling, digressing and changing direction as suits his experience, and his role as a collector of fragments and a surveyor of ruins. He becomes increasingly engaged in an epistolary correspondence with Iryna Zarebina, a woman seeking refuge from the war in Ukraine…

The narrative arc, then, concerns this email correspondence with Iryna. It starts when she emails him:

Dear Professor, I am reading one of your books on the doorstep of war. You once wrote about war eloquently, so the critics said. I do not believe anyone can write eloquently about war. If you could find the time, could you please answer that question. (p. 29/30)

He doesn’t reply “of course”, because he suspects it’s a scam. But, the problem is, it’s got him thinking about his ‘”eloquence” in writing about war’. At this point, readers who have read the epigraphs will remember that one of them quotes John Hawkes*, who said, “Everything I have written comes out of nightmare, out of the nightmare of war”.

War – Ukraine, Vietnam, World War 2, and others – is, then, a constant presence in the novel. As is the aforementioned Iryna because, although she’s “probably a bearded scammer”, he does write back. He asks her about the “dogs in the Donbas”, hoping this “will shove aside the irritating accusation of eloquence”. And so a correspondence begins in which war and dogs, among other issues, are discussed. In other words, dogs become another thread in the novel, as do toilets, aging and its depredations, solitude, the writing life and more.

This is a “big” book, one that, as I’ve intimated, will be read differently by different people. Those concerned about where the world is heading will engage with the issues that mean something to them. Those of migrant background might most relate to his experience of discrimination and othering. Those of a certain age will relate to thoughts about mortality and managing the aging body. (To test or not to test is one question that arises.) Those of a literary bent will love the wordplay and clever, delightful allusions (and wonder how many more they missed. I loved, for example, the allusions to TS Eliot’s “The love song of J. Alfred Prufrock”, a poem about anxiety and indecision which reflects Quin’s inner questioning about action and inaction. I also loved the wordplay that made me splutter at times.) And those interested in the form of the novel will wonder about where this is all leading!

“the unreliability of reason” (p. 232)

There is so much to write about this book, and I’m not sure I can capture the wonder of reading it, how ideas are looked at from every angle – inside out and upside down – in a way that illuminates and stimulates rather than confuses. It’s quite something.

I’ll try to explain something of this through two of the interweaving motifs – toilets and dogs. Both mean multiple things as Castro is not one to close things off. So, early on, toilets reflect the sort of cleaning work migrants must do to support themselves, as Abe does at University. Later, they are part of the aging person’s concern about bowel health. But, in between they could also symbolise feelings of disorder and helplessness, his “anxiety in the gut”, including just coping with “the difficult things of ordinary life”. Similarly dogs epitomise the instinctual, simple life, but, in stories like their being used for target practice, they could also represent innocent victims of war. Here of course, I’m sharing my personal responses to these motifs. There are many others.

No wonder Quin worries about the writing life. It’s something he, a writer, is driven to do, “it pushes fear into the background”, but does it achieve anything?

I’ve always believed it is the novel that carries all the indirect notes of empathy. It may even be violence that brings empathy to war and its suffering. It may be anything. Yet, the plasticity of the novel bends to all the obtuse emotions and accommodates them. Then all is confined to the scrapheap of having been read, having been experienced, having been second-hand and second-read. Major libraries are throwing out paper books. (p.140)

Chinese postman was my reading group’s September book, and it proved challenging, but that is a good thing. We had a lively discussion during which disagreement was not the flavour, but a genuine and engaged attempt to understand what Castro was on about. Whether we achieved that, who knows, but I am glad I have finally read Castro. I won’t be forgetting him soon.

* Wikipedia des John Hawkescribesa (1925-1998) as “a postmodern American novelist, known for the intensity of his work, which suspended some traditional constraints of narrative fiction”. !

Brian Castro

Chinese postman

Artarmon: Giramondo, 2024

250pp.

ISBN: 9781923106130