I’ve written about the Prime Minister’s Literary Awards before – more than once in fact, as you will see if you click on my link. They were created in 2007 by our then new Labor Prime Minister, Kevin Rudd. What heady days they were. These were, at the time, Australia’s most lucrative literary awards, and were among the first of the major awards, when they instigated this in 2011, to provide a cash prize for shortlisted books. Awards were initially made in two categories – fiction and non-fiction – but gradually other categories have been added for poetry, children’s fiction, young adult fiction, and Australian history.

I do wonder though about the ongoing support. In 2010 the winners were announced on 8 November, then in 2011, it was 8 July, and in 2012 it was 23 July. Last year the winners were announced on 15 August, and this year they were announced tonight, 8 December. Why such inconsistency? Most major literary awards keep pretty much to a schedule, but this one is all over the place. Does this suggest a lack of commitment? I had started to think this year that they weren’t going to happen – until the shortlist was suddenly announced on 19 October.

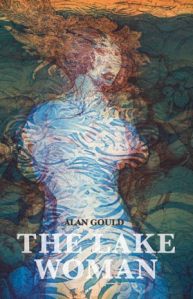

I enjoy following these awards – and I’m primarily talking fiction here – partly because there is often something left field about them. Three winners – The zookeeper’s war by Steven Conte (2008), Eva Hornung’s Dog boy (2010) (my review) and Stephen Daisley’s Traitor* (2011) – didn’t win any other major award (as far as I’m aware). And the shortlists have included books that scarcely, if at all, popped up elsewhere, such as Sophie Laguna’s One foot wrong (2009) and Alan Gould’s The lakewoman (2010) (my review). Given that the arts is a subjective business, I like seeing different works being recognised. I can’t believe that there are only 6 or 7 books worth highlighting each year – and yet that’s what often seems to be implied when you look at the shortlists in any one year. (I suppose, though, if you are one of those 6 or 7 you hope that multiple listing will result in your winning at least once?)

Anyhow, it’s now time to announce this year’s winner of the fiction award – and it’s a joint award: Steven Carroll’s A world of other people and Richard Flanagan’s The narrow road to the deep north (my review).

And I can’t help giving a special mention to a couple of other winners:

- Poetry award: Canberra’s gorgeous Melinda Smith with her collection Drag down to unlock or place an emergency call (published by the lovely little poetry press, Pitt Street Poetry). I haven’t read this, but I have heard Smith speak and mentioned her in my post on Capital Women Poets.

- Non-fiction award: another joint award – Gabrielle Carey’s Moving among strangers (on my TBR) and Helen Trinca’s Madeleine: A life of Madeleine St John (my review).

The Australian history award was also made to two books. I have no idea what the authors think about all these joint awards, but as you can imagine, I like that the love was shared.

I do hope these awards continue, and hopefully on a more routine schedule.

Congratulations to all the authors, and their publishers, who won this year.

* I have been wondering about what has happened to Daisley, but I read just today in a catalogue from Text Publishing that he has a new book out in 2015, Coming rain, set in Western Australia in 1955, the year he was born! I’ll be looking out for it.