I can’t remember a time when I wasn’t a feminist, but Bill suggested that, for his AWW Gen 4 week, I “could ‘review’ The female eunuch by discussing your experience of Women’s Lib at uni”.

I replied that I could probably do “Reflections of a 1970s feminist” but that it wouldn’t be exactly what he was thinking. The thing is, I chose to go to a new, progressive university (Macquarie) though many of my peers from school preferred the “name” one (Sydney). I’m sure things weren’t perfect at Macquarie, but in my experience women were treated well, there. It had no baggage of “traditions” that the older male-dominated universities had, and its academics seemed invested in creating something new. I think that made a difference.

Macquarie’s motto is Chaucer’s “and gladly teche” (from the lines “gladly wolde he lerne and gladly teche”). I always thought it a bit strange that the motto focused on “teaching” more than “learning” but now I think it’s inspired, because it reminds the academics that “teaching” is where it all starts. All this is to say that, although I read The female eunuch during this time and was strongly affected by it personally, I wasn’t aware of an active feminist presence on my campus. However, there are things I could say about growing up from the 50s to 70s and why Greer made such an impact on me.

A baby-boomer childhood

My father, like many men of his between-the-wars generation, wanted a son, but his first two children were daughters, me first, then my sister. A son came along, but a few years later. I never felt unloved or unwanted – indeed, I was very much loved – but we grew up, in the main, in a traditional role-oriented household. We had an intellectually frustrated but devoted stay-at-home mum and breadwinning father. Household tasks were largely gendered, with Mum looking after inside, and Dad outside – and we children followed suit. That’s how it mostly was back then, so it didn’t seem particularly strange.

Conversely, it also didn’t seem strange that my sister and I were encouraged in our education, that it was assumed that we’d go to university and on to work, and that marriage and children were sort of assumed some time down the track but were never focused on. Consequently, while my sister and I were expected to help with “women’s work” like washing and drying dishes after meals, it was only on weekends and holidays. Schoolwork came first.

They were schizophrenic times, then, and jokes were often gendered. One, I particularly remember, concerned junk car yards, which were called, by the menfolk as we drove past, “ladies’ driving school”. Yet, my Mum drove and we were encouraged to get our licences. It didn’t make sense. Was it a “little” attempt by men to retain their superiority as we encroached on their domain?

Feminism to the fore

As the 60s moved into the 70s, however, Women’s Liberation, as we called the second wave of feminism, came to popular attention. I read The female eunuch within a year or so of its publication, in my first year of university. It bowled me over, giving structure and a theoretical underpinning for how my thoughts were developing. It was both easy and not easy being a young woman then. The free-love hippy movement of the 60s gave women increasing freedom to be themselves in dress and behaviour – but old habits die hard and the pressure to conform to ideals of beauty ran alongside. Moreover, as Kate Jennings made clear in her famous Front Lawn speech in 1970, the appearance of increasing freedom for women was not matched by the reality. The recent documentary Brazen hussies documents these times very well. I was forging my own path through this, eschewing the trappings of “beauty” and dressing naturally, comfortably, sans make-up, hair colour, high heels, and so on.

Again, my family supported me. No comments were made – to my face anyhow! – but the women’s movement did not pass unnoticed. Another little anecdote, I remember, concerns my paternal grandparents, born in 1889 and 1893. They were kind, generous people, but Grandpa wasn’t averse to little digs at “women’s libbers”, including a time when Gran surprised him by suggesting she occupy the front seat of the car when my Dad was driving them home after a visit. Gran got the seat, and their marriage continued its loving way. Gran was great fun, and did her best to keep up with the times.

Moving along into the 1980s and 90s, I did marry and have children, and I chose – it was a choice – to work part-time at a time when part-time work was not well-supported in the Australian (then Commonwealth) Public Service. My good friend and work colleague had a child at the same time, so we proposed that we job-share. That was quite a saga, one too long to fully tell here. We were supported by our immediate boss, a woman a few years older than we were, and, generally, by the rest of the senior management, but we did face opposition from a few, including the female head of HR. With no regulations in place at the time for administering permanent part-time work, we needed the support of HR to make it work on paper (which included applying for leave-without-pay every week for the hours we weren’t working). We got there, eventually, but it was disappointing to find the greatest opposition coming from (some) women.

Through all of this and other feminist challenges along the way, Germanine Greer’s arguments – and those of the writers I was reading in Ms magazine, edited for a while by Australia’s Anne Summers* – underpinned my confidence that my choices and ideas were valid.

Reading women writers

It was around this time – that is, in the 1980s – that I started prioritising women writers in my reading, a priority I have maintained ever since. Virago Press was one of the inspirations for this, and I regularly scanned bookshop shelves, looking for the identifying green spine. There were other women-focused presses around, but Virago editions, in particular, inspired many of us, as we realised just how many great women writers had been forgotten. This is when I fell in love with Elizabeth von Arnim, Maya Angelou, Zora Neale Hurston and E.H. Young, to name a few.

However, this is Monday Musings on Australian literature, so I thought I’d close on the Australian novelists who inspired me at the time. But first, back to my Mum. I grew up with reading parents, and my Mum had on her shelves – besides Jane Austen and other favourite classics – Henry Handel Richardon’s Australia Felix trilogy, Eleanor Dark’s The timeless land, M. Barnard Eldershaw’s A house is built, Eve Langley’s The pea pickers, and Thea Astley’s first novels.

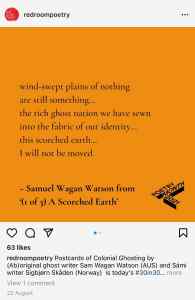

So, when women’s writing started to really take off again in the 1980s I was attuned – and started reading, in that decade, novels by Thea Astley, Jessica Anderson, Elizabeth Jolley, and Olga Masters, to name a few. These writers, their contemporaries and those who followed them, including now, First Nations women writers, have added immeasurably to my understanding of myself as a woman and a person. They have helped me be comfortable in my shoes, but have also shown me where things need to change, personally and politically. I would not be who I am today without them.

A fundamental feminist principle – obvious to those who understand, but not to those who, for their own reasons, wish to remain obtuse – is that feminism is not about the sexes being the same but about all people being equal in terms of rights and respect. Germaine Greer puts it a different way in her Preface to the 21st Anniversary Paladin edition of The female eunuch. She says it’s about freedom, “the freedom to be a person, with the dignity, integrity, nobility, passion, pride that constitute personhood”, freedom from fear and hunger, freedom of speech and belief. As she says in this 1991 edition – and unfortunately it’s still true – things have changed, but not enough. It’s therefore wonderful seeing a new generation of feminists picking up the baton. They don’t always get it right, anymore than previous generations did, but womanhood – and personhood – is, I believe, in good hands.

* Anne Summers, of course, wrote another now-classic Australian feminist work, Damned whores and God’s police (Lisa’s post)